Monday again already!

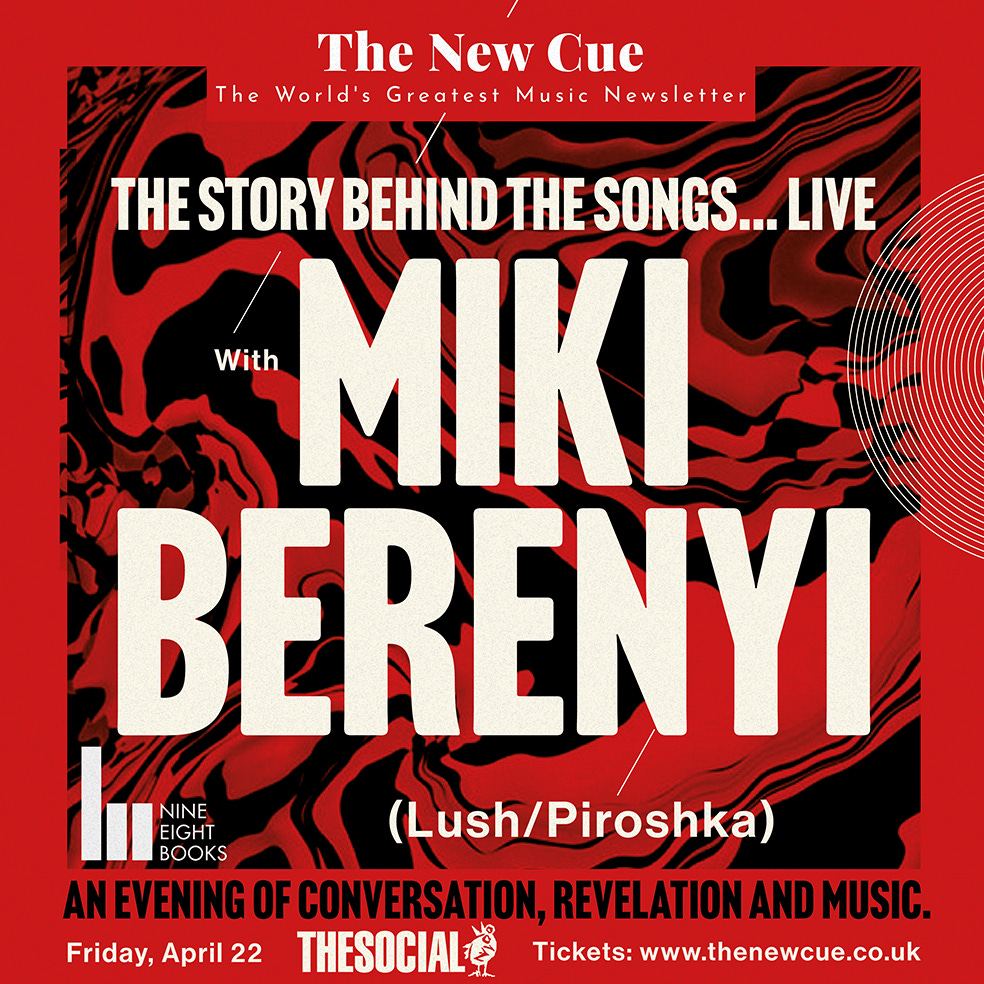

That’s annoying isn’t it. But don’t worry, we’ve got a great chat with Kae Tempest to get your week rolling. Before we get to that, don’t forget we’ve got our first TNC live event coming up in a few weeks. It takes place on April 22 and we’ll be speaking to Miki Berenyi for an evening of the Stories Behind The Songs: she’ll trace the tales behind the songs she wrote and sang with Lush, playing some of them, as well as giving us a sneak preview of her forthcoming memoir in conversation with Ted. Tickets are £7.99 and available by clicking through here:

See you there!

Enjoy the edition,

Ted, Niall and Chris

Start The Week With… Kae Tempest

Kae Tempest is one of the most visionary voices in modern British culture. The South Londoner is an award-winning poet and best-selling author, a novelist, playwright and spoken word performer, but music is where it all began. Next month, Kae releases a brilliant new album titled The Line Is A Curve. Like their previous three solo records, it’s been produced by Dan Carey and is their most sonically adventurous effort yet, a mixture of imposing synth soundscapes and delicate, downbeat electronica built around Kae’s dexterous wordplay. It’s also the first record since Kae came out as non-binary in August 2020. Kae spoke to Niall over Zoom last week to explain how it all came together, why it’s been years in the making and to tell us how often they hop onto the punchbag that’s hanging from the wall behind them during the interview…

Hello Kae, how does it feel to be gearing up for a new album release?

It feels good. It’s been a long time coming, I’m excited.

Starting at the end, how did you feel when you finished it?

There’s a few different ends to it. We wrote the album, recorded all the live parts, Dan produced everything, we mixed it all in some way and then I recorded the lyric as one live take over the top, so we got to the end of that day and it was like, ‘Well, this is amazing, we’ve done it’. Then we put them together and so then we’d finished it. But we never had that thing, because it was lockdown, when we could get a few people round to the studio and play them the album. Not long ago, we had that moment of a few friends and loved ones coming to the studio and we played the record, because for all the other albums it’s an important part of the album, that you finish it and listen to it with people. That was a really memorable moment because there’s something about hearing it through other people’s ears. You’re just like, ‘Fuck, it’s real, it’s coming out, we did it!’

Is that normal for you, that you’d lay the vocal down in one take like that?

No, it’s something that I learned on the last album, The Book Of Traps And Lessons, that really what I want, to get the most amount of truth in the vocal and to get the best vocal is I want to do one full pass of the whole record, a live take. It’s old school, that’s how they used to do it, the vocalist comes into the studio and they do the whole album. There’s something about the endurance of it that creates this feeling in the lyric that you can’t get if you do 150 takes at each verse. I just want to do the whole thing, I want to rise to the occasion of that.

That must have meant that by the last track Grace, you were just emotionally spent?

Yeah, you’re there, you’re where the listener is because you’re going through it. If somebody listens to the album as a whole piece, which I hope they will, then I’m with them on that journey the whole way, it’s in real time, it’s happening. By the time I got to Grace, I was ready to say those words.

I got a sense of real forward momentum in the music. Is that something deliberate or have I just made it up?

Yeah, I really wanted the tracks to bleed into each other the way they do. That’s the genius of Dan Carey, we made all the songs, we knew where they wanted to be, and I was like, ‘Dan, they need to be linked, we need to go from this song into that song, I don’t want any silence’ and then Dan would work out this beautiful little run on the piano or like something on the synth, so all of that stuff that happens as one track leads into another that gives you this sense of propulsion and forward motion and movement, it’s me coming up with this idea and then Dan just totally solving the problem and rising to the occasion and using his expertise and his genius.

In terms of your writing, were you writing from a clean slate or was there stuff that you already had you brought into it?

Pretty much, everything apart from Salt Coast. That was the only one, everything else I’d just go in the studio and I’d just start writing. Smoking was a real voice note that from a real backstage at a real festival, I wrote that and sent to Dan and we use the real recording. And Salt Coast was a poem that I was working on that I bought to Dan and he scored it. But everything else, I’d just write in the studio. We get going and it starts to happen.

What was your favourite moment of the whole process?

Every single moment is my favourite moment, fuck man, I love it so much, I love working on music with Dan. Writing These Are The Days was just fantastic. It was lockdown, that summer when we hadn’t been allowed to be together, that really hot, weird dead summer, the first one where nobody really knew what was going on and finally, I got to be in with Dan in the studio. Just that feeling, ‘at last we can do this thing that we can do’. That song just fell out of me. It was a beautiful moment.

When you started working on the record, did you know it was going to come out under the name Kae Tempest?

No, because we started working on it ages ago, The way that I work doesn’t really make any sense from the outside looking in, but I work so many things at the same time. Often I’ll spend a week working on something and then because of everybody’s schedule, I won’t get back to it for six months. My memory is pretty scrambled but I think the first sessions for this record happened when I was touring Let Them Eat Chaos, so in between all that there’s a whole album and everything else and books that come in between, but I think we wrote Priority Boredom and the music for Smoking in that first session and I’m pretty sure that was the end of the Let Them Eat Chaos tour.

Ah ok, when we spoke a few years ago you alluded to their being another record on the boil somewhere and this is it…

Yeah, I’ve always got one on the go.

With your huge stovetop.

Exactly! The thing is, when we were in lockdown, we probably had about half the songs by the time we hit lockdown. They had the shape and we knew where it was going and I had the title. I came out around that time, that summer. So no, when I first started making the album, I didn’t know.

Did coming out change anything about your relationship with the songs?

It’s changed a lot in my life and in my experience of my life, but my relationship with the music, with the work, has always been very deep, it’s deeper down. It’s beneath my experience of my body and gender or anything. When I go to the music and I go to the poetry, I go with my soul, it’s not really about my physical experience in the world, it’s another place that I go to when I’m making music or when I’m on stage so it didn’t affect it like that I don’t think.

Does your relationship with your words change the further you get away from them?

Yeah, like with anybody really, you look back on things like, ‘How did I manage that?’. It’s interesting, sometimes I go and do spoken word gigs. Over the course of the last two years, I got a couple of gigs in Europe, I did something in Barcelona, something in Venice and I decided to pick up a load of older poems and do them all together, just see what would happen by putting them all together and weaving a new narrative out of pre-existing poems. It’s something I like to do in my performance sometimes, so in that sense I went back, I looked at the old books of poems and I have this sense of familiarity but I see the new now. It’s reassuring to feel this current going through all the work, obviously I hope that I’m developing as a writer and I’m getting better or I’m learning how to be less overwritten, how to have more patience, or more refinement, or all these things that you hope for as a writer. But still there’s a current going through all the work that feels familiar and it resonates with me.

Is it a different type of nerves for a spoken word gig than when you’re doing your songs?

Yeah, completely. When you’re alone, with 30 minutes, 40 minutes, an hour and a half, whatever it is, to fill with words, I get really tangled in the words, they’re entirely everything, they create everything and they invite me in and I feel kind of less nervous because if I decide that I’m not feeling something, or if I drop the words, or if I lose focus, I can just go anywhere I want because there’s nobody else with me, it’s like a solo piece. In that sense, I get less nervous but the approach is different, the stakes are a bit higher when you’re out onstage with the set and lights and music, and usually the audiences are bigger for those kinds of shows. My heartbeat races in a different way for those kind of shows.

What do you get out of doing music that you don’t get in your other artistic guises?

I get so much out of music, I began with music. The musicality of my language is almost its primary function for me and when you take it away from the music for too long, and it’s just the words, it loses a dimension. There’s something about the placement, the flow, the way that the music and the lyrics give each other depth and focus and clarity and all that. Sometimes when I’m rapping with music, it’s like I’m playing an instrument, that’s how it feels. I can get lost in it in the same way that you would if you were playing the trumpet or playing the guitar. I go in that way and I feel a satisfaction that is unique to that world. But then I feel a different kind of satisfaction from working on a play text or working on a book of poems. They satisfy different parts of my creative appetite.

You’ve got some great guests on the record, like Kevin Abstract on More Pressure, Lianne La Havas on No Prizes and Grian Chatten from Fontaines D.C. on I Saw Light. How did they come about?

The thing about the previous records is the focus was so tight, to try to tell these long stories and everything like that, there was no space for other voices. But on this album, I just knew I wanted to collaborate with people and have community with me. Grian is someone I’ve known for a while, I’m lucky enough to have met him through Dan Carey, who worked on the Fontaines records. I just absolutely fell for his poetry. I think he’s a true poet and I think we have a kind of affinity. There’s something between us, some recognition of words, the way he feels about his words, I feel like ‘yeah, you’re a poet,’ I feel that in him. I’ve seen Fontaines D.C., I’ve seen them in little pubs and at Ally Pally. I knew I wanted to work with Grian, I’ve wanted to work with him for ages and I just thought, ‘yeah, maybe this would be amazing’. He just came down and delivered his poem. I didn’t know what was going to do, I didn’t know if he was going to sing or shout or rap.

Okay, so it’s not like you prescribed an idea you had to him?

I wrote the first verse and the hook and sent it to him and just said, ‘what do you think?’ And then he just came through and that’s what he’d written. It was beautiful.

What’s your favourite season?

Autumn. I love it. It’s a really good time to write, because things are changing, there’s something in the air, the brightness of the sky, the coldness. It’s hard to write in the summer because you just want to be out there all the time and then when autumn comes around, you know you’re getting a good four months to write, I do my best writing in autumn and winter.

I can see a punchbag there behind you. How often do you go on it?

This is the room that I work in, the punchbag was my mate Jim’s, he brought it round cos his missus was like, ‘we’re getting this out of the house!’ and I was like, ‘I’ll have it!’. What’s good is that if I’m working on something and I need a break, if I can do even 30 seconds or a minute or three minutes if I’m feeling really particularly frustrated, it completely resets the blood in your brain. It’s actually fucking brilliant to have it over there.

Yeah, that sounds good.

Don Paterson, who’s my poetry editor, I once went to his house to do an editorial and I saw that in the study where he works he’s got an American pool table, a full pool table in his room where he’s writing his poems. I was so inspired because poetry is so intense, you can sit there and be writing a poem and it’s like you’re building all this scaffolding in your mind, it’s so hardcore that just the idea that you could just take a break go and have this methodical different headspace, so the punchbag is my pool table.

When was the last time you heard a lyric and thought, ‘I wish I’d written that’.

I don’t really get ‘ah, I wish I’d written that’ but I love lyrics, I’m more like ‘Thank you for writing that’, that’s my feeling. I saw Jay Electronica at Jazz Cafe a couple of months ago. For me, his lyrics are divine. I was listening to JID this morning, the DiCaprio 2 album. I was listening to Johnny Cash singing this song Redemption Day and it’s not him that wrote it, it’s Sheryl Crow, and it’s fucking stunning.

As someone who loves lyrics and words, does that mean the bad lyrics really stick out for you?

Yeah, what can I say about that... There’s a time and a place for lyrics of all kinds. I’m a total softy for totally cheesy power ballads, 90s 80s emotional roller coaster songs. I love it. But there are certain things about certain kinds of lyrics that I find it hard to listen to. Sometimes I can get a bit oversensitive to lyrics, I can’t bear it sometimes, but I just tell myself to chill out when that happens.

You get on the punch bag.

Yeah!

Thanks for your time Kae!

Take care, bye!

ND

Kae Tempest’s new album The Line Is A Curve is out on American on 8 April. Kae heads out on a UK tour next month, head here for tickets and details.