Morning,

I hope you had a good weekend. We used to work for someone who went through a three-month period of making everyone in the office sit in a meeting room together on a Monday morning and take turns telling the room what they’d got up to over the weekend. I occasionally wake up thinking of those days. We were mostly in our in our thirties and forties at the time. Some of us were parents of young children, including our boss. He was asked to leave the company not long after.

Today, we have an exclusive interview with Graham Day, Britain’s greatest living garage rocker, as well as the former senior divisional officer of Kent’s fire brigade. If you feel like you don’t know enough about Graham’s career with The Prisoners, The Mighty Caesars, The Solarflares, The Gaolers, The Forefathers, The Senior Service or Kent’s fire service, read on. Actually, read on anyway.

Enjoy the rest of your day, drop us a line and let us know what you get up to. We’ll see you on Wednesday.

Ted, Niall and Chris.

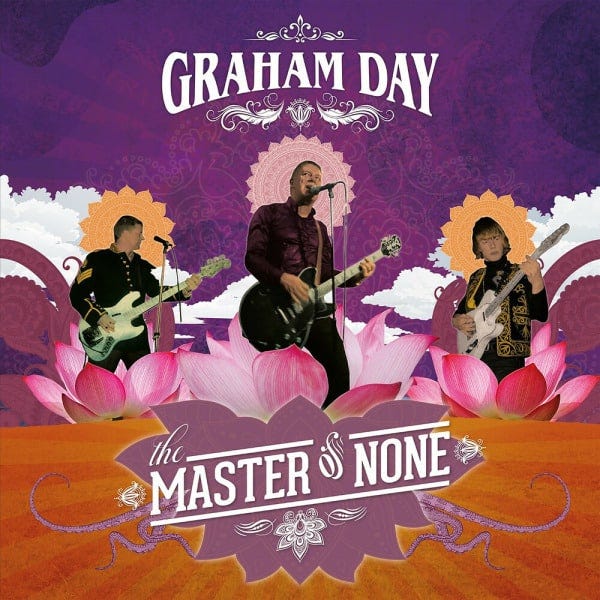

Start The Week With… Graham Day

Graham Day is best known for the seven or eight years he spent playing guitar and singing with The Prisoners, the R&B-influenced psych-garage-mod band from Chatham in Kent that split up after four studio albums in 1986 when he was just 23. That sentence will drive Graham understandably nuts, as he’s been a prolific writer, recording artist and performer outside The Prisoners too, putting out many albums with half a dozen other brilliant groups across the following four decades. You can have a listen to some of them alongside The Prisoners on this playlist I made:

The Prisoners were The Small Faces infused with a carefree DIY attitude and, alongside their Medway mates The Milkshakes, fronted by Billy Childish, they were a stylish, chaotic oasis of cool in the moribund mid-1980s. Lee Mavers of The La’s famously complained that he wanted to make records in that decade that sounded of real ‘60s dust but couldn’t find anyone who knew how to do it. He should’ve gone to Chatham: The Prisoners and The Milkshakes had stockpiled it all.

Graham Day split The Prisoners when the pressure of making money from music started to rear its head. He’s only ever wanted making music to be a hobby, which is probably why he’s made so much of it. If he was American and career-minded, he’d no doubt be Jack White. He’s certainly as talented a singer and guitarist, but instead he’s kept music as something he enjoys doing rather than something has to do. Ted met him in the bar at St Pancras Station one lunchtime to talk about Graham’s new album, The Master Of None, which he made on his own during lockdown, amongst other matters.

So, it’s Master Of None’s release day today and as we were saying before I pressed record, you’re annoyed about the vinyl delay…

Annoyed might be a bit strong, but yes. At my age you just want the record out because you don’t know how long you’re going to have to keep doing it. You worry you might die before the record comes out.

It’s been a long time since Graham Day’s made a record hasn’t it?

I’d have to look at Discogs! It’s a been a while. Ten years maybe?

What have you been doing in that time?

I played in an instrumental band called The Senior Service. We’ve had two albums out and a mini album. I have a Gaolers album to record in about three weeks. That was the one that I should’ve done with the band but turned into my own record.

I saw on Facebook a video of a Prisoners reunion recently, too.

Well, there was a gig by a band called Auntie Vegetable, a covers band with Allan [Crockford, former Prisoners bassist], Bruce Brand [ex-Milkshakes and many other groups], Sexton Ming. James Taylor [ex-Prisoners keyboardist] plays in that. They only played a handful of gigs in the mid-80s, a piss-take psychedelic nonsense band. For some reason somebody wanted them to play again so I was there because I was curious to see how awful it would be. Meanwhile, there was a plot hatched by Johnny [Symons, Prisoners drummer] and James to see if they could get us to play a few Prisoners songs together again.

Wouldn’t it be nice?

Well, we’ve avoided it for 21 years so far. I wasn’t expecting it and was busy trying to run for the bar when they were calling my name. I was thinking, ‘Oh God’. I’d had a lot to drink. But I thought it would be rude if I didn’t get up. We played a few songs. I played one in the wrong key. Got the verses round the wrong way in another. It felt really good though. Johnny was great. He’d been practising, the bastard.

Why have you avoided it for 21 years?

Because people go on about The Prisoners so much. Bear in mind I was 15 to 23 when they were going. The last gig we played was the 18th of September 1986, two days after my 23rd birthday. I’ve done so much since – admittedly very similar to The Prisoners, I’ve not taken much of a departure. But to have people going on about The Prisoners, I have felt it a bit insulting. I understand the nostalgia, but I feel I’ve done a lot of better stuff since then.

It’s because The Prisoners were part of your youth, but they also symbolised a lot of fans’ youth. There really wasn’t a better band playing in pubs and clubs in 1984 to 1986 in London or anywhere in England at that moment. You symbolise something for fans.

Yeah, I know that. I do. Of course.

And you quit before ruining it. Although you did reform for gigs briefly in the ‘90s.

Some of those gigs were better than others. I’m really glad I did The Forefathers, because that was my way of coming to terms with the fact that everyone really still liked The Prisoners, thinking perhaps I should embrace it rather than fight it. That was good. We thought we’d do it for a year and did for six or seven. That band was just a platform to play Prisoners songs, but after a while we ended up playing Solarflares songs – a post-Prisoners band – because you can’t play a lot of those Prisoners songs without the organ. The last gig we did we didn’t play any Prisoners songs so I thought that’s a good time to stop.

Tell us about making your new album, The Master Of None.

It was an accident. Eddie Piller was badgering me, saying he was relaunching his Countdown label and wanted me on it. ‘I don’t care what you do! Just do it!’ I like to be in a band and record an album in four days. That’s what I do. But I came to terms with computers, Logic, over lockdown. They’re brilliant! I had no idea. You can get some great sounds, so I realised that I might be able to do the album alone after all. I said to Ed that I had this Gaolers album written that we were going to record the week before lockdown, maybe I can do that. It was just something to do. Anyway, I recorded it all on my own and, yeah, it came out alright.

That philosophy, the DIY punk attitude, just get on with it, I associate with your generation of Medway musicians, The Prisoners and The Milkshakes, existing in your own musical, stylistic bubble, away from all other contemporaries. What is it about the Medway delta?

Everyone I knew was in a band, or two or three bands actually. That was it. We all played together. It just seemed to be that in our area there were a lot of bands into the same kind of music who all picked up instruments. I tried to just be in one band at a time, but I did end up in The Prisoners and The Mighty Caesars at the same time.

It was the norm. We didn’t appreciate in The Prisoners what was happening. Strangely, in the last five years or so a lot of those people have started playing again together and we now have more Medway venues, which is a surprise.

It was odd that there was such a large ‘60s-focussed scene in such a small area though, all armed with that Billy Childish DIY mindset.

That all came from The Milkshakes I think. They were four years older than us, I’d seen them in The Pop Rivets, a bit punk, a bit ‘60s. I’d see them around town. I became good friend with Bruce Brand from the Milkshakes, he’d play me The Kinks and Pretty Things, that changed my life. We didn’t know anything about recording but The Milkshakes took us under their wing. They just had a two-track, big old fashioned tape machine. ‘No need to go to a studio lads, stick that in your rehearsal room and there’s your album.’ I mean, we went our own way, but they were right because all the studios were nightmare then. Engineers just wanted you to sound like everything in the charts, which in 1983 was not a very good for a band with an organ player. We’d bring in Who and Small Faces records and say we wanted to sound like that. ‘Oh, I can’t do that, but I can make you sound like Phil Collins.’

Avoiding real studios helped give you your sound.

Yes, getting the drums was the main thing. Not having a big 80s rock drum sound. The Milkshakes were a big influence in that DIY recording and sound aspect, for sure.

You can hear in your recordings you learning as you go along.

First album, A Taste of Pink, was recorded and mixed in two days. Ha! The next one, The Wisermiserdemelza, was a much bigger production, which we hated. The third one we nailed it, The Last Fourfathers. The first and third was us live, how we sounded live, but we did some tinkering to the third and that elevated a bit.

The song writing on The Last Fourfathers took it to a new level too.

There’s a lot of people credited on that for songwriting. Knowing a bit more about it now I’d probably get the credits for all the songs, but because we were a band we sliced the pie up a bit. I mean, James came up with some amazing organ lines and although they’re not the song they certainly contributed. I think Russ Wilkins gets a credit for thinking of a guitar sound. We were only 21. We didn’t know what the fuck was going on.

The Last Fourfathers came out in a truly dreadful time for music, 1985, particularly for guitar music. It’s a kind of miracle. It’s a perfect record, the perfect description of that band. It’s one of my favourite albums, I still play it fairly often.

Horrible era. I actually think The Prisoners got even better after that, live anyway. We sorted of turned into early Deep Purple by the end purely because James was becoming so good at the organ. Then we kind of ruined it with that horrible last album – I don’t know if you should write that because Eddie put it out. [Sorry Eddie]. The songs were good on In From The Cold, but we were in the studio so long it sucked all the life out of it.

And that’s when you called time on it.

The other thing was that Jamie was getting too good for us, really. He wanted to do his own thing, which made sense. There wasn’t a better organ player that I knew of. Early James Taylor Quartet were really, really brilliant. First two albums, really good. We’d played together since 1979, ’80. We needed to try different things.

Was there a gig you played in Europe naked, or was that a myth?

No. There was a gig in Holland with The Milkshakes where a radio company came to broadcast it. We got so pissed. We used to alternate the slots with The Milkshakes so they went on first that night, got rat-arsed, and they invaded the stage during our set. When we came back on for the encore we were all naked. I was alright, I had a guitar in front of my bits. Not so good for Johnny on drums though.

After The Prisoners, what were your horizons?

I just thought that was the end of music for me. No, really. I’d had enough.

Did you become a fireman?

I did. I thought I’d better get a job, become responsible. All that music caper was over now. Eventually, Allan came round and said I’m no longer in the JTQ, me and Wolf want to be in a new band, so… The Prime Movers were formed a couple years after The Prisoners. Felt good, for the first album at least. You can hear a string breaking in one of those songs on that first album. I thought, ‘that sounds OK!’

That’s very much your musical ethos.

It’s more about capturing a performance than being perfect. The experience The Prisoners had with In From The Cold was [producer] Troy Tate trying get it to sound perfect and it ended up lifeless. I learnt a lot from that album, mainly that I never want to record like that again. The engineer had recorded the drums gated, which means you don’t get the sound of it ringing out. You just get a dead thump. It means we could never fix the drum sound. Tragic really. You can’t polish a turd.

So are you still in the fire brigade?

I retired four years ago. I was with them for 30 years, 1988 until 2018. I get a fire brigade pension: I’m a pensioner. Music is a hobby and that is one of the reasons why The Prisoners had to end. I didn’t like having to earn money from it. That felt false and anti-creativity. It’s always better as a hobby. I don’t want to worry about making a record next year or what people will write about my music.

You never got your dues.

No, but people still want to listen to my records and me to play gigs, and at a scale I’m comfortable with. If The Prisoners were to play now with the original line-up, and it’s the 40th anniversary of A Taste Of Pink next year, then I imagine people would want us to play in quite big venues and I’d hate that. That’s not for me. I’d rather play here, in the corner of this pub.

What was your life like in the fire brigade?

I really enjoyed it. It was only stressful the further I got promoted. The early days were just like being in a band, really. Good camaraderie. Just a bunch of mates and you never know what you’re going to face. I had some grim things to do, but I had fun along the way.

Were you in danger?

Probably. No, plenty of times. You train for it so you know someone will drag you out. Got dragged out a couple of times. Had the ceiling collapse on me a couple of times. I got to senior divisional officer. My final job was that I was responsible for all the fire stations in Kent. The operational side. I was always a people person, interested in that side rather than the gadgets, fire engines. I know how to put a fire out, though. It’s a much bigger part of my life than being in bands was.

TK