Well well well…

May the fourth be with you!

Boom! Do you get it?! May the fourth…May…the 4th (the force)…be with you? Yes? Hello? Helloooo? Jean! Is this thing working? Can you get hold of IT support and see if they can fix it, please? I don’t think anyone can make-out my hilarious word-play.

Anyway, here we are on a Wednesday, with an atypical free Wednesday edition as we missed our usual freebie Monday letter because of the bank holiday. Drink it in. Today, we have an extract from Sylvia Patterson’s classic music press memoir I’m Not With The Band, all about her years as a champion pop star interviewer. This particular chapter is about her time as a nipper at Smash Hits in the mid-80s. (Yes, they called their readers viewers).

Why are we running an extract from Sylvia Patterson’s book? Well, we’re running it to whet your appetite for this Friday when, between the hours of 6.30 and 8:00 pm, she’ll be on the stage of The Social in London’s fabulous Little Portland Street alongside her old Hits and Q sparring partner Tom Doyle in conversation with Ted Kessler (me), chatting music press memories and interview calamities/triumphs/regrets. There are still a few tickets left at £4.99 available here.

BUT we also have a pair of freebie tickets for New Cue readers. Is that you? Do you want a hot date on Friday evening in the heart of London’s swinging West End? Early enough start to also enjoy dinner, drinks and dancing afterwards? If so, just send us an email entitled SYLVIA AND TOM to thenewcue1@gmail.com and it shall be done (for two of you).

Enjoy the edition. See you Friday!

Ted, Niall and Chris

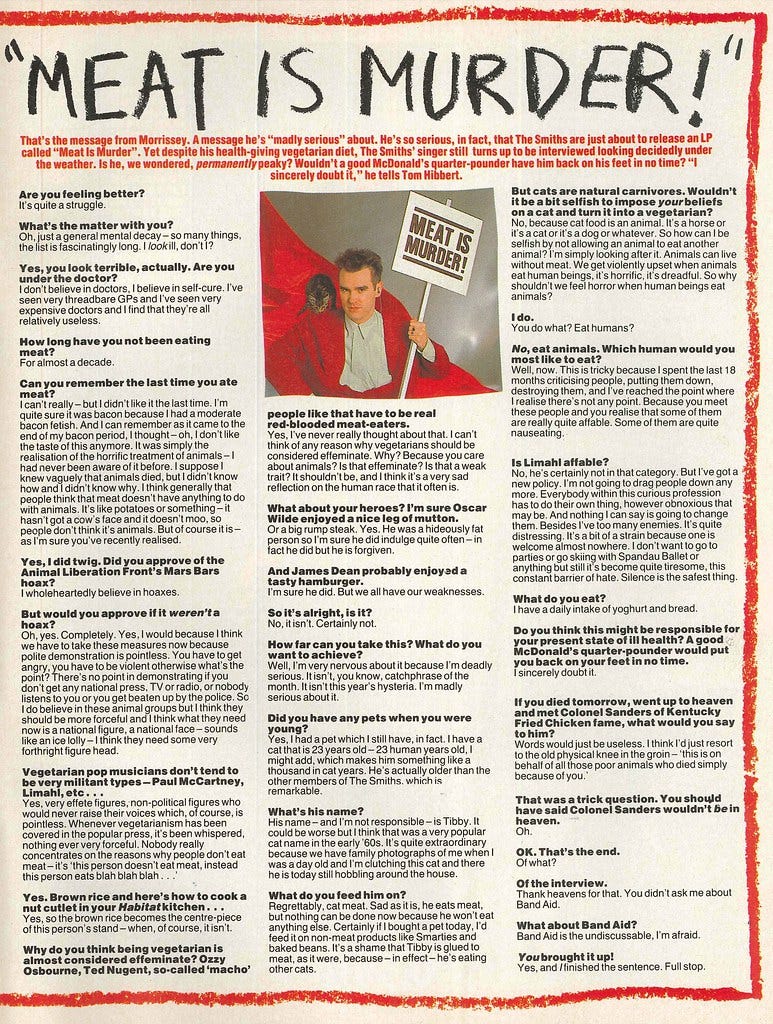

Lost In Print… Sylvia Patterson

Sylvia Patterson is one of the most distinctive and influential British music writers of the last thirty (forty) years. She was a 20-year old Staff Writer at Smash Hits during the mid-late ‘80s heyday when it sold a million copies every fortnight, and later became a star freelancer for NME, The Face, Q and loads of other places that didn’t treat her with the care her prose deserved over the ensuing decades. She’s currently writing furiously away towards the deadline for her second, as-yet-to-be-announced book, but in the meantime, here’s an extract from I’m Not With The Band, about her time as a new member of the Smash Hits staff…

HAPPY HOUR

The spirit of Smash Hits in February 1986 was to be found in a tea-towel. Not just any old tea-towel with a print of a mimsy Cotswolds cottage on, but a comedy tea-towel invented by Tom Hibbert, a prize bestowed upon whichever viewer Black Type deemed had written that fortnight’s best – i.e. most ludicrous – letter, possibly something about being hit on the head by a gigantic picnic table. Meticulously illustrated by the man I’d soon know only as ‘Hibbs’, it included his handwritten eulogy to wonders-of-washing-up-wonkiness.

‘WASHING UP – THE BLACK TYPE WAY!!’ it declared, before offering a handy instructional list. ‘Tap! Just twiddle the knob and – in a flash! – your sink is brimming with piping hot water!! Plug! Pop snugly into sink-hole and – voila! – sink stays full every time! No more “sinking feeling”!! Scouring pad! A short, sharp scrub and your “oh-crikey-I’ve-singed-the-beans-and-they’re-all-stuck-to-the-bottom-of-Mum’s-best-pan” problem is solved in jig time!! Lawn mower! (Not much use for washing-up, actually . . .)’

This was the planet I parachuted into from certain-death-in-Dundee, bringing the words ‘jings’ and ‘crivvens’ into every printed sentence, a planet in polar opposition to Gordon Small’s K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple for the Stupids), a publication keeping it eternally surreal for the students and grown-ups who now also read Smash Hits and found in its language, irreverence and visual japes a teen-pop version of Private Eye edited by Spike Milligan in a particularly juvenile mood. On the first floor of 52–55 Carnaby Street (Just 17 and Kerrang! were housed in the floors above) was a world free from all forms of cynical agenda, where wheezes were invented only for the sake of the wheeze, a world where U2 had finally ‘taken their place in the lineage of The Greats, like the Thompson Twins’.

The staff was largely populated by indie kids, most in their early 20s, mostly Smiths ‘apostles’ and John Peel devotees without a trace of indie snobbery who also loved pop in all its forms. They included huge-eyed, clever and inscrutable features/reviews ed Chris ‘The Toff’ Heath, the first person I’d ever met who’d been Oxbridge-educated. Assistant design ed Jaqui Doyle was a dazzlingly fashionable Dubliner who once illustrated the lyrics to The Smiths’ ‘Shoplifters Of The World Unite’ with a backdrop photo of a Tesco carrier bag which would’ve resulted, today, in a publisher-buckling lawsuit.

The Ed, Steve Bush, was an enigmatic man who seemed to view the world as if through a gigantic set of inverted commas suspended in outer space; he was often to be seen in giggling cahoots with features/design ed Vicky McDonald, a bright, intense young woman in a fetching pencil skirt and sweeping indie fringe, the staff member who found my job application ‘dossier’ by accident, adrift like shipwrecked flotsam under the art department desks where it had languished for a full month (while I psychologically perished 500 miles away). She, too, had saved me; without her I may well have been incarcerated in a Tayside prison after a Brew-led GBH incident with ‘one of life’s real characters’.

And right next to my staff writer’s desk perched Tom ‘Hibbs’ Hibbert, deputy ed, rat-tat-tatting with those index fingers across a standard issue electric typewriter all day long. Hibbs was by some distance the most uniquely brilliant creative mind I had ever encountered, a man about whom I knew nothing whatsoever, neither age nor background, though he did, I’d once been told, test acid for a living in the 70s. Perhaps this was something to do with the sort of subject matter he’d routinely conjure from the ether, like the cast of characters which came to dominate Black Type, the letters page which exemplified the anarchy of absurdism at the heart of Smash Hits, its anonymous fortnightly ululations encouraging nationwide obsessions with Una Stubbs, Dickie Davis, the Eurovision Song Contest, aristocratic pop chanteuse Princess Stephanie of Monaco and the extravagantly-titled ‘fruit’ drink ‘Um Bongo, Um Bongo, They Drink It In The Congo’.

Black Type’s world included officious personnel – Uncle Disgusting, Mr and Mrs Perkins, Mr Perkins’ secretary Miss Pringle (who Perkins had the hots for) – Black Type himself being a disembodied voice more likely to have a conversation with ver Kids about the bungled fitting of a Hotpoint washing machine than hunky merits, or otherwise, of Huey Lewis And The News. Ironic inverted commas now floated throughout copy like exuberantly tossed confetti (Gary Glitter was forever ‘fresh’ off a UK tour) while the pop star nickname was an escalating sport: no longer merely the mid-80s inventions Paul ‘Fab Macca Wacky Thumbs Aloft’ McCartney, Lord Frederick Lucan of Mercury and Dame David Bowie but Mark ‘Horrible Headband’ Knopfler out of Dire Straits, Mark Unpronounceablename out of Big Country and Morten ‘Snorten Forten Horten’ Harket out of A-ha. The viewers adopted these immediately, soon sprinkling them throughout the pen-pal service RSVP, the page where viewers listed their pop faves and looked to contact other fans – and where Smash Hits helpfully printed out the full names and addresses of kids as young as 11. (Don’t think that one would fly today, eh, pop pervs?)

The office itself was a riotous, open-plan explosion of Jiffy bags, cassette tapes, 12-inch and seven-inch cardboard envelopes housing vinyl delights and those brand new, state-of-the-art silver discs called CDs which everyone associated with the dullard’s favourite, Dire Straits’ Brothers In Arms (one million CDs sold in 1985 and a format, therefore, not to be trusted). The office housed two multi-desk ‘islands’: writers/section editors clattered away on typewriters (usually with accompanying, individual ashtrays) opposite the production/art department, whose desks were besieged by a jetsam of flat-plans, double-page spreads, coloured paper, marker pens, glue, paints, spray paints, paint-fixer spray cans and furling scrolls of printed-out proofreading galleys. That such an obvious fire hazard was not only tolerated but never questioned is made all the more boggling by the persistent strikes on boxes of Bluebell matches.

There were no health ’n’ safety rules, no editorial rules and what felt like no bosses either: the publishing bigwigs we collectively knew as The Baron (publishers Emap Metro) perhaps astutely keeping their oars aloft from the editorial characteristics: a style not so much warm and friendly as blasting you upwards through a glitter cannon of jollity that shouted ‘piping hot!’ in your earhole, its fully formed editorial personality now turning Emap from a cottage industry contender into an actual publishing empire.

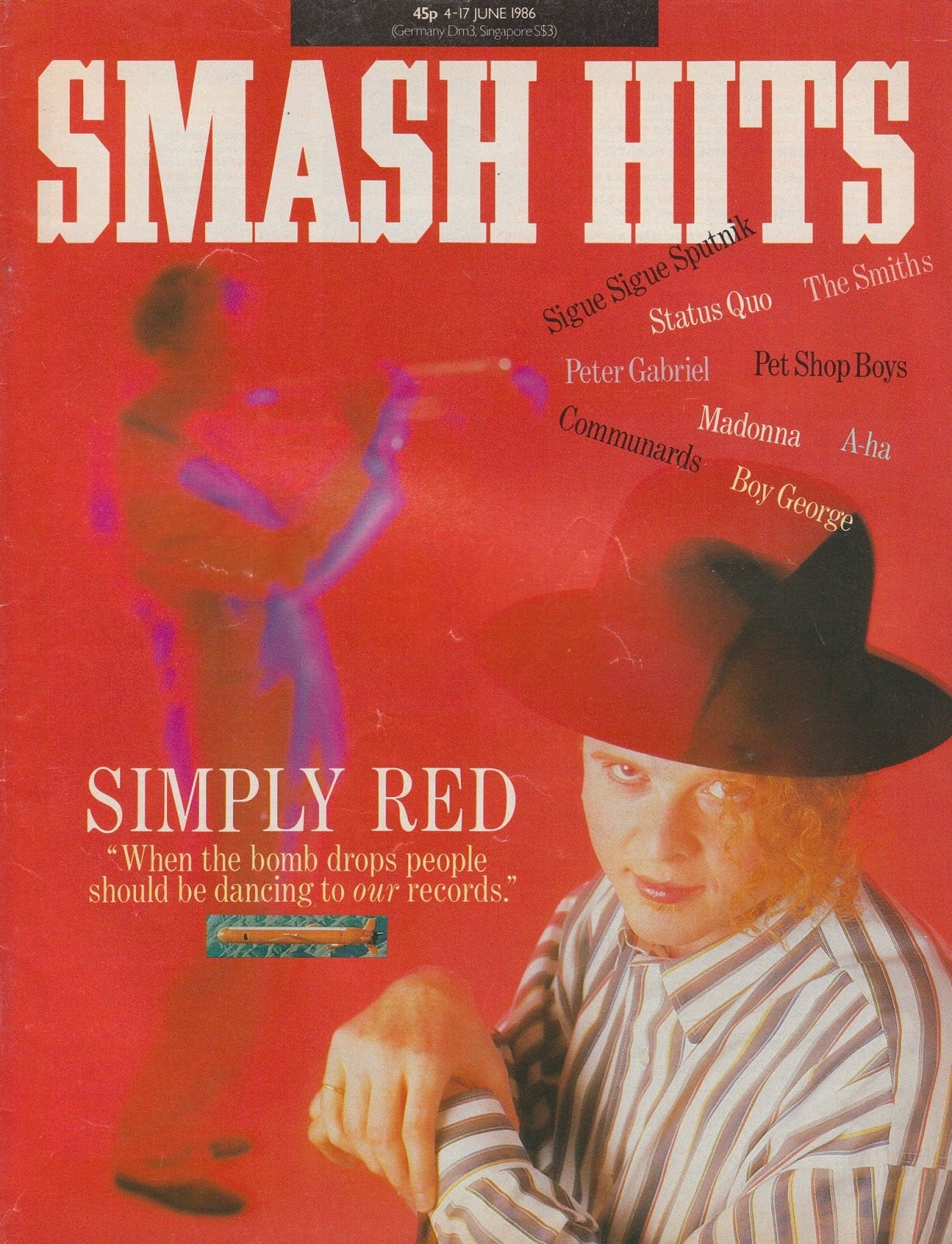

I didn’t have a clue what I was doing. Three months in, my very first cover story was with Mick Hucknall out of Simply Red, on whom I had an enormous crush (like several thousand other women in his unlikely, and then largely unknown, secondary career as an incorrigible crumpeteer). We spent one hour together in the offices of the mighty WEA Records, the righteous flame-haired soul brother persistently eulogising on the global success of debut album Picture Book, which was en route to selling two million copies worldwide.

Naturally, I had to steer him away from dreary sales figures, encouraging instead a stirring tirade against the dominant political force of the day. ‘I think Margaret Thatcher has done more damage to this country than the Second World War,’ he soon harrumphed, formidably. ‘She has destroyed this nation. If a person over 40 loses their job, they’re not going to work for the rest of their lives – that’s the basic truth of the matter. The very people who probably voted her in! Look what she’s done to education! Can you imagine sharing books when you were a kid? In infant schools they’ve got one between the lot of them. Unbelievable.’

Despite the many members of the public who believed ver Hits was only interested in favourite colours and fancy hair, it was as loud a hailer for idealism as its inky, stinky cousins on the weekly music press. Hucknall soon began pepper-spraying opinions on the ‘racist, sexist, biased right-wing media’, on the aforementioned inky music press, ‘a cess pit of hypocrisy’, and tirades against religion, child pornography and the nuclear bomb, ‘when the bomb drops people should be dancing to our records!’

Here, I wondered, as I’d wonder a thousand times throughout the forthcoming decades, if the rich, famous and successful person before me had any clue whatsoever as to The Meaning Of It All, any clue to human happiness. ‘Well, my first love is music,’ mused a bewildered Hucknall. ‘I am happy. Definitely. I fight unhappiness – you have to.’ For permanently vaporising romantics like me, however, it was also LOVE I wanted to know about. ‘Oh, here we go,’ he cringed. ‘Well, the first girlfriend I ever had was when I was 11. I thought she was extremely wonderful. It lasted about a week. When it finished I made a pathetic attempt at killing myself! I just lay in the middle of the road and waited for a car to come. But it never did. I had to get up because I got bored! Have I ever been in love? No. In the present situation it’s just impossible to make it work.’

Was he, though, romantic? ‘No I’m not!’ he cackled. ‘I hate what romance is supposed to be – all that sending flowers and “darling, I love you” and all that smoochy stuff. What I find romantic is just being yourself and being accepted as yourself – now that’s romance. I very rarely tell people I love them, I’ve only ever meant it about twice. I don’t think that’s sad. It makes me quite happy really – for what’s to come. I’m free. Completely free and I love it.’ He looked momentarily mortified. ‘You’re not going to write all this rubbish down are you?’

Naturally, I fell ‘in love’ with Mick Hucknall. And when the first copies of the new issue arrived in the office, featuring his dreaminess on the cover, I immediately had a mentally ill idea: I’d personally take a copy to Hucknall, who was then on a UK tour with Simply Red – and the moment he saw this marvellous representation of himself in print, with the feature entitled ‘I’ve Never Been In Love’, he would immediately see the folly of his romance-free existence and fall deeply in love with me. I found out where Simply Red were playing, which hotel they were staying in, paid for a flight to Edinburgh, booked into a B&B (single bed, floral nylon sheets, blue candlewick bedspread) and sat on a chair in the hotel foyer Hucknall was staying in until he eventually sashayed through the door.

‘Mick?’ I squeaked, as he stalled, startled in his tracks. ‘Uh . . .’ he managed, no doubt with stalker klaxons whooping through his mind. ‘I thought you might like to see this?’ I ventured, holding Smash Hits tantalisingly in mid-air, eyes beseeching him to see what had so obviously appeared before him: it’s me, don’t you see? THE WOMAN OF YOUR DREAMS. ‘Um . . . yeah . . . thanks,’ he mumbled and strode off deep inside the hotel. Crushed, I schlepped off to a pub, then back to the B&B where curled up, alone, under the crackle of the nylon sheets, I stayed awake, cringing for a full eight hours. Only today, 30 years later, can we confidently assume I was surely the only blatantly propositioning woman the flame-topped Lothario didn’t even attempt to seduce in the whole of the 1980s . . .

Normal daily Hits life, thankfully, was less mortifyingly naïve. Safely bunkered in Carnaby Street, I filled the news section, Bitz, with my little-known indie heroes, just as I’d gotten away with it at Etcetra, with fewer goth madmen involved. Forever lurking in Review Nook, I’d be permanently on the blower with the likes of rambunctious London folk troupe The Woodentops, be-cardied Glaswegian schminders The Soup Dragons and swirling Mancunian guitar spooks The Chameleons, interviews mostly about their pre-‘fame’ lives as members of Maggie’s Three Million.

‘We were completely skint and on the dole,’ chirruped Mark Chameleon in July ’86, ‘jumping up and down in front of our bedroom mirrors with guitars with no strings on. I’d rather have been doing that though and getting me £18 a week, as it was then, than getting £50 a week to pack vinegar. I never wanted a proper job. I never wanted to grow up either. In fact, I’m still 16 in me head. Who wants to be grown up? Bills and children . . . no thanks.’ Hurrah!

Soon, indie heroes were everywhere, including the mighty Richard Butler out of the Psychedelic Furs, announcing he was psychologically unwell. ‘When I’m by myself for any length of time late at night, I start going a bit . . . round the bend,’ he declared. ‘I have to have other people around otherwise I lose grip really easily of what’s real and what’s not. I keep thinking I’m having a heart attack. I go for a run around the block and I think that if I am having a heart attack, I’ll die, but if I make it back I must be alright.’ Crumbs.

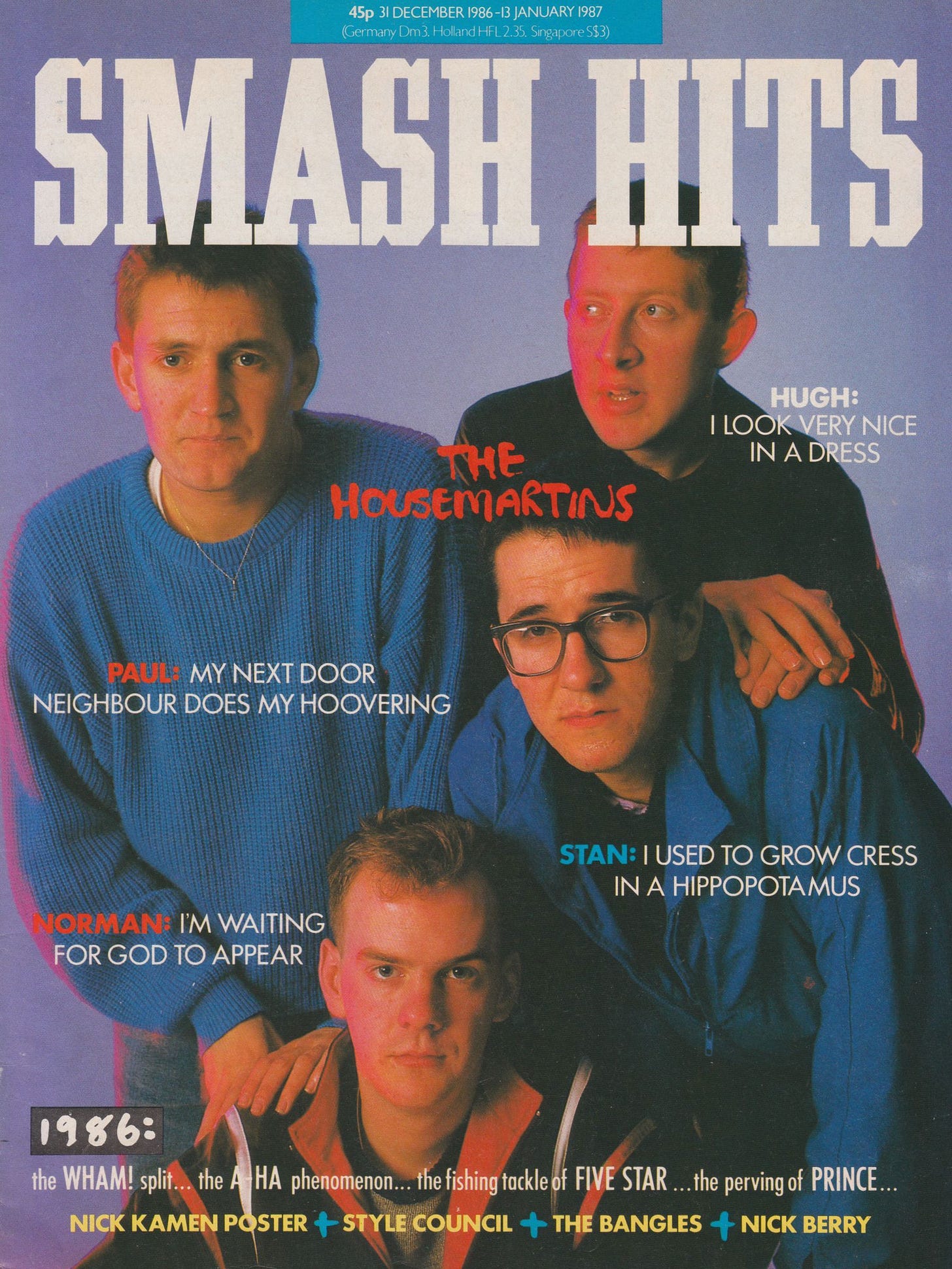

I spent a day in London with my Marxist indie-geek heroes, The Housemartins, who were none too keen on the interview lark, especially my beloved Stan, who agreed to speak officially only after eight hours in his company, six conversations as to whether he should or shouldn’t ‘do interviews’ and several cans of ‘best’ ‘bitter’. Have you ever grown parsnips in a gumboot, I inevitably wanted to know, and Stan – being a proper pop star – ran with the wheeze. ‘No, but I used to grow cress in a hippopotamus,’ he announced, gamely. ‘Y’know those pottery hippopotamuses? I had a square yard in the back garden which my parents had given me and there I used to grow the cress in the hippopotamuses . . . oh, let’s waltz instead, shall we?’

Here, Stan out of The Housemartins, two years into my profound obsession with his bespectacled brilliance, waltzed me round a grassy traffic island knoll by a car park somewhere in central London while continuing to eulogise on his mossy-fingered skills, ‘I also grew pansies and we had these lovely Victorian plum trees . . . so as you can see I’m an incredibly boring person and I’d rather you didn’t print any of this because I’ve got nothing to say!’

Wibble . . .

The more mayhem we could muster, it seemed, the more Smash Hits began to sell. And sell and sell and sell . . .

Click here for tickets, or on the image above if you’d rather. See you there!