Happy Monday,

Before we start the week with our old pal Bernard Butler, we are happy to announce our next event.

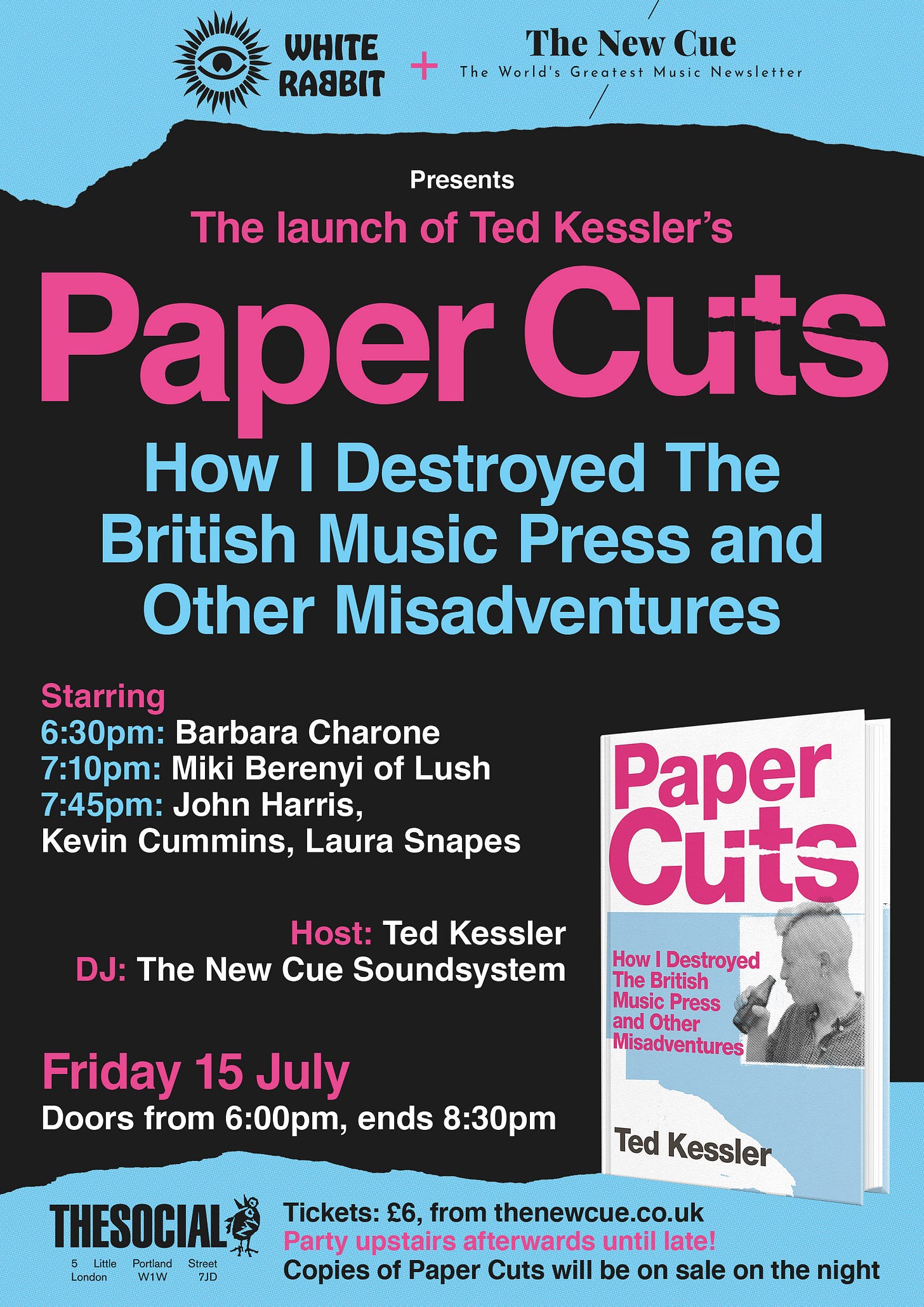

On July 15th, downstairs at The Social in London’s Little Portland Street, between 6:00pm and 8:30pm, we will be hosting (alongside our friends from White Rabbit) the launch for Ted Kessler’s new book, Paper Cuts - How I Destroyed The British Music Press and Other Misadventures (yes, Ted is writing this, please do not break that fourth wall). We are extremely excited about the line-up, which involved blackmail and obscene flattery to put together.

We’ll be asking various legends of print and song to spill the beans on the inner workings of the music press across the eras.

* Music PR’s Big Beast, Barbara Charone, will be telling us tales of her career looking after the likes of Madonna, Depeche Mode, Keith Richards and many more. We will not discuss that she is now a director at Chelsea with her though.

* Miki Berenyi - the singer and guitarist with 1990s music paper darlings Lush - will tell us about her journey through the music press, what is was like to be the object of the magazines' desires and occasional derision, what appearing on the cover of NME felt like.

* A stellar panel of journalism royalty from the across the ages will convene to describe and compare their adventures in the music press: John Harris, ex-NME staffer, Q features editor and Select editor; photographer Kevin Cummins whose pictures of everyone from Joy Division, Sex Pistols through Happy Mondays, Oasis and beyond are as well known as the records themselves; Laura Snapes, the Guardian’s assistant music editor, will tell us what it was like to join the NME from school and become one of their main writers at the end of its print era.

Afterwards, we’ll party in the upstairs bar and on the street until late. Tickets are six quid, here!

Now onto today’s edition as Bernard Butler tells Niall all about his collaborative new album with Jessie Buckley. Over to you Bernard and Niall! That’s got a nice ring to it, hasn’t it?

Enjoy the edition,

Ted, Niall and Chris

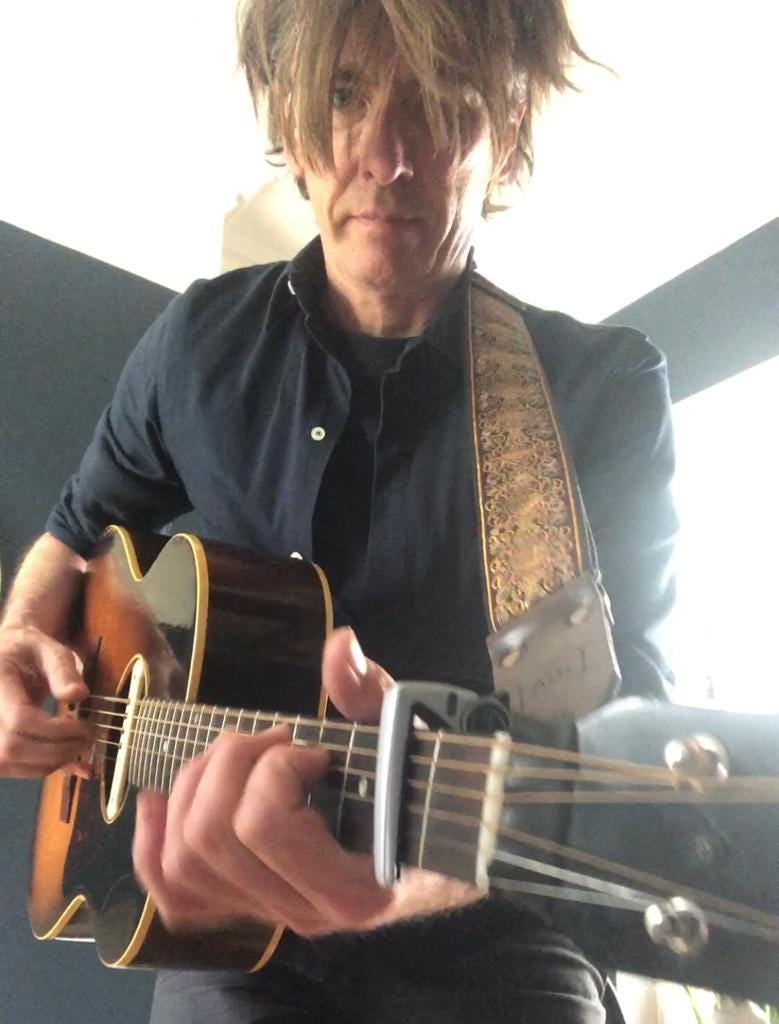

Start The Week With… Bernard Butler

On Friday, Jessie Buckley and Bernard Butler release their collaborative new album For All Our Days That Tear The Heart. On paper, their union seems a little unlikely. One is an Oscar-nominated actress whose recent credits include The Lost Daughter, Men and I’m Thinking Of Ending Things and the other is a musician who started his career as the guitarist in Suede before becoming both a collaborative supremo and successful producer. The record, however, makes perfect sense of their pairing. It’s a woozy, swaying country album, soaked in a strange sort of sadness that feels uplifting at the same time. If you’ve seen Wild Rose, you know that Buckley can sing. And Bernard Butler has long established that he’s really good at all the other stuff (he can sing too). It’s a lovely record. A few days ago, Niall spoke to Bernard about how it all came together before ruining everything by mentioning Suede in the final question.

Hello Bernard. Where are you?

I’m just at home in Crouch End.

How’s your Friday morning going?

I’ve done the dog walk, mixed a track, thinking through what I’m doing for the rest of the day, trying to get songs in my head, arranging equipment. I’ve actually done a lot over the last few hours!

That’s a hectic start to the day.

It’s been quite busy.

Do you make to-do lists?

Yeah, I send myself an email called “Stuff”. I put the title Stuff and so I can always search “stuff” in my inbox. That’s my thing.

Do you like to have a lot of plates spinning at the same time?

Yeah, sometimes your head is a bit frazzled and that can get messy. If there’s too many plates spinning, then things start to suffer. I don’t like it when I can’t 100% focus in on things in detail in the way I want to. If you’ve got too much stuff going on, you tend to miss fine details and that annoys me. The other thing that annoys me is when I run out of time and then I get a text about something like, ‘the microwave’s broken’ or, ‘did you know there’s no toilet roll?’ and all I’m thinking about is, ‘I’ve just found that five minutes to learn that song and actually there’s no toilet roll in the house and that’s more important.’ That’s the kind of stuff that interrupts me. Apart from that, I love working on lots of things. It’s always been the joy of what I’ve done in music and how I’ve got to here is that I put myself in a position when I was quite young to always be moving, always collaborating. And that’s really given me the joy of everything I’ve done more than anything, just creating that space for myself that now I think people understand that and look forward to that rather than expect me to be doing one thing,

Yeah, and you’ve done so much now, your CV is huge.

Yeah, and I think there’s always a point where people think, ‘why aren’t you doing that one thing you did a hundred years ago?’ and now I feel that people expect the opposite, which is what I’ve spent 25 years trying to carve out for myself. It’s a really enjoyable life, I meet lots of people and every day is another musical project or idea that we’re working on in different ways and you’re just constantly replenishing yourself and reinventing yourself in little ways and starting again, and so everything is always fresh and exciting for me. The turnaround of people is really exciting, I’m always involved with so many people, different musicians. It’s such a joy to me, that I can find myself around people who I’m in awe of as musicians, and it makes me constantly have to tap myself on the shoulder and say, ‘be better, kick yourself up the arse’, because you’ve suddenly got this amazing bass player or percussionist or something and you’re like, ‘oh, okay, I’m in the same room as you so I better up my game again.’

What do you tell people what you do for a living?

I’m a musician. That’s it. I’m a musician. I’m really proud to be a musician. That’s a great, wonderful thing. If you told me as a kid that I’d be a musician for life, and be around musicians and that turnaround of musicians, and meeting people who do different things and from different genres and areas of music all the time, and having to communicate with them on a musical level and try and interpret ideas and learn to be articulate and communicative with people about music and also to interpret other people’s ideas and turn them into music and find processes that work, that’s what I do. And in whatever capacity that is, whatever hat I have to wear, whether I’m playing guitar or I’m singing or I’m playing the drums or writing or if I’m just watching and helping people, it’s being musician. That’s at the core of it all.

Congratulations on the new record. It’s fantastic.

Thanks so much.

It seems like the right time to release it, I’m getting good June vibes from it.

Do you think so? That’s great. That’s funny, because the beginnings of it were written during June, when me and Jessie met and the first few songs were written it was in summer of 2020. Do you remember that first lockdown was quite nice and, if you weren’t ill, you were secretly enjoying the sunshine and the peace and quiet for a bit. It was just after that time, it was good weather and it was quite peaceful and contemplative and that’s the space that we found ourselves in when we when we started working together, it was like a vacuum. It is a June record, yeah.

How did that that sense of contemplation seep into the songwriting?

Because the two of us found ourselves together, strangers, and because of lockdown, we couldn’t use a studio or anything, we just sat together in my kitchen with the door open and we didn’t have any microphones, no production, nothing, we had a pen and paper, and we talked. Me and Jessie would send each other stuff during the week, words, book references, or piece of poetry or something, films she’d been watching, and then when we met, we had all this stuff laid out and we just talked about it. It would be a case of she’d seen something and I hadn’t, and she’d describe it to me, she’d describe the essence of something, so without seeing a whole film or reading a whole book, you’d get a picture and then you’d find a thread from that that we talked about. In the same way, we’d grab books, and be flicking through books from shelves, grabbing a paragraph or a page and saying, ‘what does this mean?’ without reading the book. This was the whole sketch of how we wrote, taking fragments of ideas from things that were fully formed but that wasn’t our context, the context of a novel or a film wasn’t what we were interested in, it was how we took ideas, and put them into our world and our lives and our conversation. We talked and dragged all these things together and that’s how the songs evolved. It was lots and lots of conversation around words. The music was kind of like the very last thing, it was very sort of functional.

That’s interesting, because the music has such a strong sense of character about it I wouldn’t have thought it came last.

What we’d do is we’d write the songs, they’d just be on an acoustic guitar, or a piano, that would be the only backing and then Jessie singing over the top and once we had our song we recorded on a phone, that was it. And then Jessie would go home. We did this all through that summer. When it came to recording, which was the winter after that, Jessie was away, and then there was lockdown and it became a bit of a nightmare so what I did is I took these phone recordings, and rather than going to a studio and rebuilding everything, I took the phone recordings and I played music on top of them. The dynamics of sitting in a kitchen strumming is a very, very different to playing as a group. When you’re just strumming in the corner of a room, you’d kind of humming half the time and the dynamic you create in the music is very different to a performance, and we both love fell in love with that essence of it. That was the character that maybe you’ve identified, so I played stuff over that and I kept that as the essence and added little bits of piano, little bits of guitar and drums and strings and stuff. That became the musical backing for the songs.

As someone who’s been such a fruitful collaborator over the years, what’s the key to making a collaboration work?

Well, everyone has to be open, you have to want it, you have to be aware that you’re not there to go out to dinner together, you’re there to create something, you don’t have to be best friends at the end of it. As it turns out, Jessie is one of my best friends and I love her and that’s a beautiful thing when that happens, but you have to go into the mentality of that’s not what you’re there to do. We became friends really out of this and after this process. I think what I look for in the other person, I look to try and find their personality, and drag out anything that’s hidden, that’s what you want, you want to drag out the bits that people are a little bit cautious of because that’s exciting and that’s what we want to find out about, seeing how far you can dig until it kind of breaks. And you need the other person to be up for it. I’ve done this with 18 or 19-year-olds and they’re just not really up for it, they’re like, ‘No, actually, I just want to write a hit today, I want to be famous’. For me, I’m not interested in that at all, good luck to you but you found the wrong person. But if you meet the right person and you start pushing and pulling together, it becomes a thing, it becomes a unity, and it’s a unity that I wouldn’t have had before on my own and Jessie wouldn’t have had on her own, or with somebody else, it can only be what you create. It’s a joint personality and that becomes a combination of also things you’re watching and talking about and music you’re listening to.

Who that you’ve worked with have you learned the most from?

This is the current big, big thing for me and Jessie is just about my favourite thing ever that I’ve done. I produced Sam Lee’s last record Old Wow and I really fell in love with the process of watching him. He’d assembled a band, which were just extraordinary musicians, and I watched them arrange the songs, it was all about just watching them and their processes. I learned so much from that process. What Sam would do is sit in his front room for weeks and weeks or months with this bunch of musicians with no microphones, and just work and nurture the sound so it was rehearsed to within an inch of its life, the spirit of it, and the dynamics and the emotional delivery of everything so that when you go in the studio and you hit record, you’ve got it. I’ve been teaching for the last five years and a lot of young people aren’t used to going into a room and playing as a group, they’re used to making music on a laptop on their own and working in a very solitary fashion. The first thing I say to them is “get in a room with some people, get together”. I used to get groups of kids together and it was just a wonderful thing to see young people together and seeing how they can spar with each other and learn from each from watching each other’s processes.

That Sam Lee record was important in you and Jessie coming together, wasn’t it?

Yeah, it was. When I met Jessie, one of the first things she said was that she really liked that record. That was quite odd because it wasn’t a big seller or anything, very few people know that record. For me, I love it to death, I’m so proud of it and so for Jessie, this person I’d just met, to pinpoint this recording felt quite unusual to me. I didn’t know Jessie at the time, I didn’t know what she wanted and it was the first thing she said. It sent a signal for me, like ‘you’re on a different level if you know that record’, rather than wanting to write an Adele song or something. It was really important that she said that and it made me think really quickly about what I should do and how I should challenge myself from the very start. This is even before we started writing. I knew that the minute I went in a room with her, it had to be on a different level.

What was the most surprising thing about making the record?

I think the best thing about it was we’d write one song and Jessie would go away, and I wouldn’t see her for a week, and then I’d think, ‘will she come back?’. Then she’d say, “can I come over again?” Then after two or three times I was like, ‘whoa, this is starting to happen.’ The fact that she was coming back meant we were both upping our game as well, we were getting more confident with our writing. That became our relationship. We had conversations that I’d never had with anyone else, the way we talked and the way we learned to communicate. You know, I have friends I go to the football with or do silly things with, and then you have friends like this, that’s a great thing in life.

How did you feel when you finished it?

We were really relieved it happened. We had no plans for it to be released, we had no record company, we made it all in my house. I paid for it. I recorded the strings in my front room. We moved the sofas out the way and got a quartet in there.

Really! The strings sound great, have you got a cavernous front room?

I have got high ceilings, it’s a North London Victorian home with high ceilings - it’s perfect for strings! We just put a quartet in front of the telly and recorded it. Everything was done just for me and Jessie, just for our sake. That’s the way we looked at it.

Last month was the 30th anniversary of Suede’s debut single, The Drowners. Did you do anything to celebrate?

I went swimming! No, I didn’t know that. I don’t count anniversaries. Someone once said to me that if it wasn’t for the Romans, we’d have 10 months of the year or nine months or 100 months of the year and we wouldn’t have anniversaries and 20th anniversaries wouldn’t exist. I don’t really believe in it all. I’ve made lots of records and, for me, every single one holds its same value. I understand that lots of people love a certain one and another one, it’s like I’ve got my favourite Van Morrison album or Miles Davis album, and it’s different to them. We’ve all got that association. But as the person who’s making the stuff, for me it’s make it, do another one and they’ve all got the same value so I don’t have anniversaries for any of them. With me and Jessie, I just want to go and do another. I’ve made my own record, which I’m just about to finish, and I’m making another Sam Lee record, and so that’s all I’m interested in, what happens tomorrow.

Keep the plates are spinning.

Totally, more plates to spin, that’s what I want.

ND