Good morning,

Ted Kessler here. I have assumed control of The New Cue for one week in a bid to satisfy my ravenous yet seemingly unquenchable ego. Over the next few days, I’ll be offering up extracts from my book Paper Cuts alongside playlists I’ve made to soundtrack each chapter. These playlists are made up of the contemporary music I was listening to at that time or, in the case of artist-specific chapters, my favourite songs by them across their career. I think the two elements - the stories plus the playlists - really complement each other. But I would say that, wouldn’t I?

Anyway, if you like the extracts, the playlists, and are interested in reading Paper Cuts (NO OBLIGATION), then we have an exclusive offer for New Cue readers: 30% off the RRP, which I believe is the best deal out there. You just need to open this link, add Paper Cuts to your basket and then write the magic phrase of NEWCUE30 when prompted.

I’ll be back on Wednesday with another selection of extracts and music. And then back again on Thursday (my God will he never stop!?) with a bonus edition for publication day. I hope you enjoy it.

Ted (and Niall and Chris, hope they don’t resent me)

Chapter 15: To Be Someone

To Be Someone excerpt:

May 1995

The phone on the Live desk rings. I answer.

‘Hello, NME?’

‘Ted, it’s Pippa.’

‘Pippa! How are you?’

‘I’m OK, thanks. Look, I have a message from Paul that he’s asked me to deliver directly to you, so I apologise in advance.’

‘Right . . .’

‘Paul says this, I’ve written it down: “Tell that Ted Kessler that if he wants to give me a kick up the arse, he’s more than welcome to get on a train to Woking and try. I’ll be waiting for him.”’

‘Is he very unhappy about the review, then?’

‘He is. He thinks it’s really unfair.’

‘It’s a six out of ten. That’s 60%. It’s a decent pass mark.’

‘I don’t think that’s how Paul sees it. He thinks it’s more of a ten out of ten album. He’s really cross about it.’

‘Ah, look. I’m a massive Paul Weller fan. I was in the Jam fan club, Pippa. I love that guy. He was my hero growing up. It’s not personal, it’s just this record.’

‘I know, Ted. It doesn’t make any difference to him. He’s taken it very badly.’

‘But I don’t think Stanley Road is a terrible album. Some of it is brilliant. “Broken Stones” is great. “Changingman”, “Stanley Road” itself are both great. It’s just those M.O.R. ones, like “You Do Something to Me”. They’re a bit bland for me.’

‘Ted, you wrote it was “an old fart blues record.”’

‘Did I?’

‘I don’t think Paul likes being called an old fart or you writing that he needs a kick up the arse.’

‘Fair enough.’

‘It’ll probably blow over, but I’d steer clear of him for now.’

‘Understood. Sorry.’

‘Bye, Ted.’

*

June 1997

The phone on the Features desk rings. I answer.

‘Hello, NME?’

‘Ted, it’s Pippa.’

‘Oh hi Pippa! How are you?’

‘This is a difficult phone call, Ted.’

‘Not again.’

‘Yes.’

‘Does he want me to come and try to kick him up the arse?’

‘No. He’s still not over that Stanley Road review, though.’

‘That’s a shame.’

‘I told him that you were the NME writer for the cover but Paul’s not up for you interviewing him. He’s already offered to fight Stuart Bailie over his review this time.’

‘So I hear. Stuart’s quite up for it, you know. He’s from Belfast.’

‘I wouldn’t fancy his chances against Paul. Not in his current frame of mind about NME journalists. Look, he’s asked me to read you another message.’

‘OK, all ears.’

‘He says: tell Ted Kessler that he’s not a good enough writer to interview me, so they’ll have to find someone better.’

‘Message received! I will commission someone else to interview Paul Weller in that case. Any preferences?’

‘As long as it’s not you or Stuart, we’ll be fine.’

*

April 2000

Paul Weller looks at the grey brew I have placed in front on him.

‘Bit fucking anaemic,’ he summarises.

It looks terrible. Weak. Like me.

‘I’ll make us another round, shall I?’

Weller walks over to the sink in the kitchen, pours our teas away and refills the photo studio kettle.

‘This new bloke you’ve got,’ he says, dropping two fresh bags into our mugs. ‘Young is he?’

He is, I confirm.

Ben Knowles, the new NME editor, is twenty-six. NME’s youngest ever editor, as he likes to immediately tell everyone he meets. He’s the editor, I’m the features editor, an elderly thirty-one, and we are delivering some truly atrocious editions of the paper together. John Mulvey, thirty-two, is the deputy editor and trying to get away without being too tarnished by what is going out of the office onto the shelves every week, but these issues stain everyone. We are all complicit: editors, writers, designers, Stereophonics and Limp Bizkit. No one gets out alive.

Steve Sutherland had been shuffled upstairs after two years of nose-diving sales, partly because NME looked like a midlife crisis, partly because music was in a devastating post-Britpop slump that was hospitalising all magazines, and partly because those in charge of publishing the likes of NME, Melody Maker and Select had collectively lost their minds. It was the overdue comedown. Nerves were shot. Talent was drained. Sales had plummeted. People were panicking.

When advertising the editor’s job, NME’s publisher Robert Tame encouraged all senior staff to apply, asking us for detailed documents about what we’d do to arrest decline, what roles would be changed, who was in, who was out. Then he gave the job to Ben Knowles, a Melody Maker writer who’d previously been on Smash Hits.

‘I’ve read all your documents,’ Ben told me with a grin when we first met. ‘Some interesting career ideas for each other there.’

His own pitch was simple, he told me. Much shorter than mine. He was going to bring all the best writers on board. And he would put all the biggest names in music exclusively on the cover. The publishers had loved these innovative ideas, he explained.

Reality had now refocused those ambitions somewhat. The week before this Paul Weller interview, the NME cover was made up of a screengrab of Sacha Baron Cohen’s comic hip-hop character Ali G alongside the legend ‘why Ali G is the most rock ’n’ roll show on TV’. This week, London mayoral candidate Ken Livingston was on the front pretending to DJ in a brown suit with a yellow floral tie. The cover line read ‘Ken he kick it?’

‘He’s twenty-six,’ I reply to Weller. ‘NME’s youngest ever editor.’

‘That’s the way it should be,’ nods Weller, approvingly. ‘It shouldn’t be old cunts like me and Steve fucking Sutherland in charge of music.’

He places our brick-red mugs of tea on the Formica table. ‘What’s this interview about?’

‘We’ve got a new series called [swallow hard] “The Greats”, where we talk to living legends about their life’s work.’

‘Oh, I’m a great, am I? Fucking hell, last year NME said I’m a cunt. I think you wrote that.’

‘I didn’t!’

‘Now they say I’m a great. That’s how it goes with you lot. I’ve seen it all before.’

We take a moment to recap.

To Be Someone playlist…Weller, from 1977 to 2021

Part One

Lost in France

The three chapters that make-up the opening Lost In France section of Paper Cuts cover the period Kessler lived in Paris, between late 1980 and mid-’85.

Chapter 1: School’s Out

Upon his 12th birthday, our music-mad narrator and family move from central London, emigrating to suburban Paris and enrolling in a huge French state school outside the city. On the last day of his first year there, he heads into the woods behind the school with three classmates and a bottle of rum…

School’s Out excerpt:

Squeezing back into the bottom exercise yard through the fence, I spotted one of the sports teachers and appraised him of the basic facts without incriminating myself. I headed up towards the food van parked outside the gates, ordered a hotdog and, as I drunkenly scoffed it, listened to the sirens from a series of ambulances approaching the road to the school gates. Then the gates parted and the sirens rolled down towards the woods…

School’s Out playlist… Lost in music, 1980 through 1982

Chapter 2: Adventures on the Metro

Kessler’s personal stylings prove violently provocative on the streets of Paris...

Adventures on the Metro excerpt:

Gare Saint-Lazare to Saint-Nom-la-Bretèche–Forêt de Marly

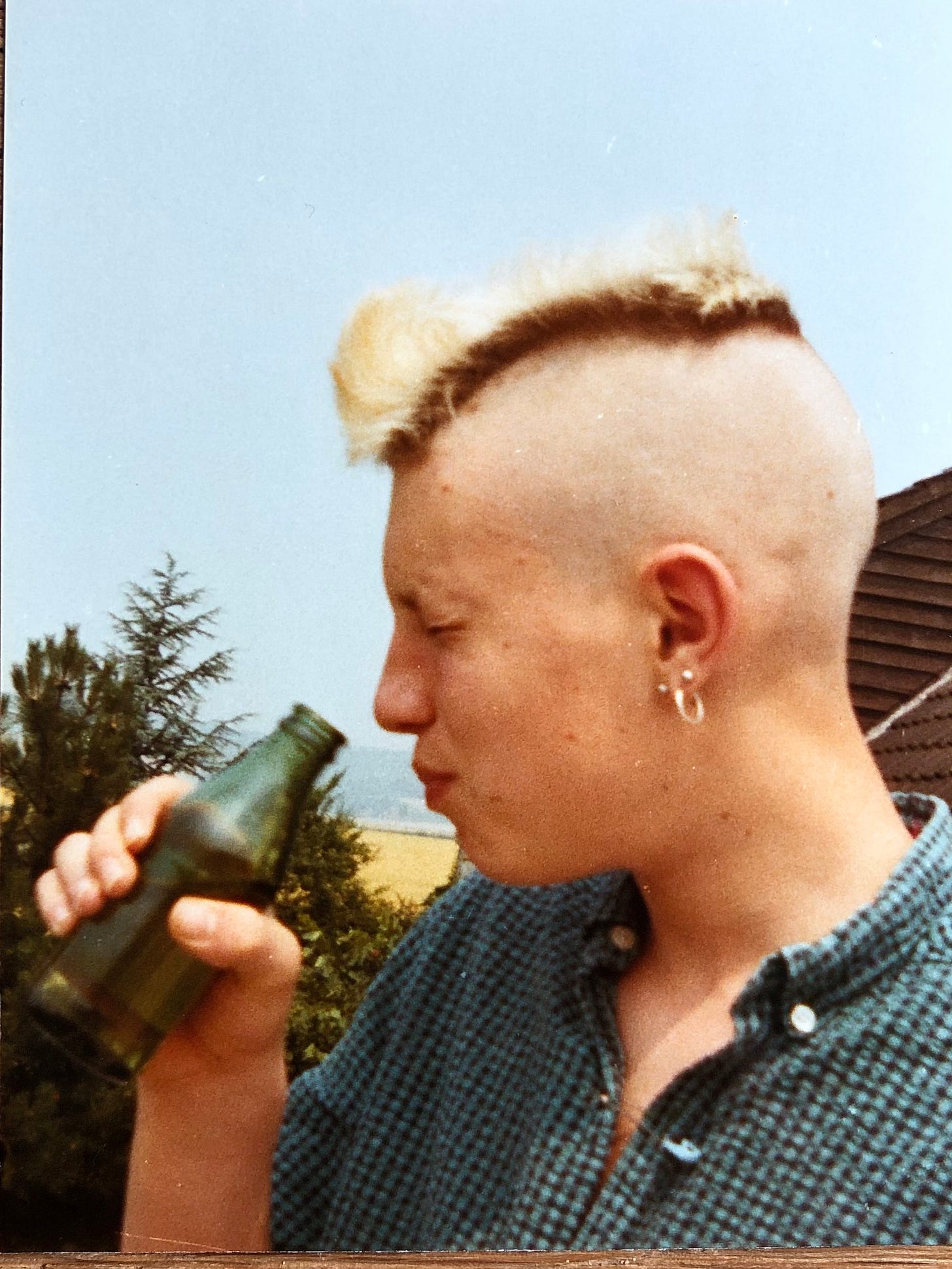

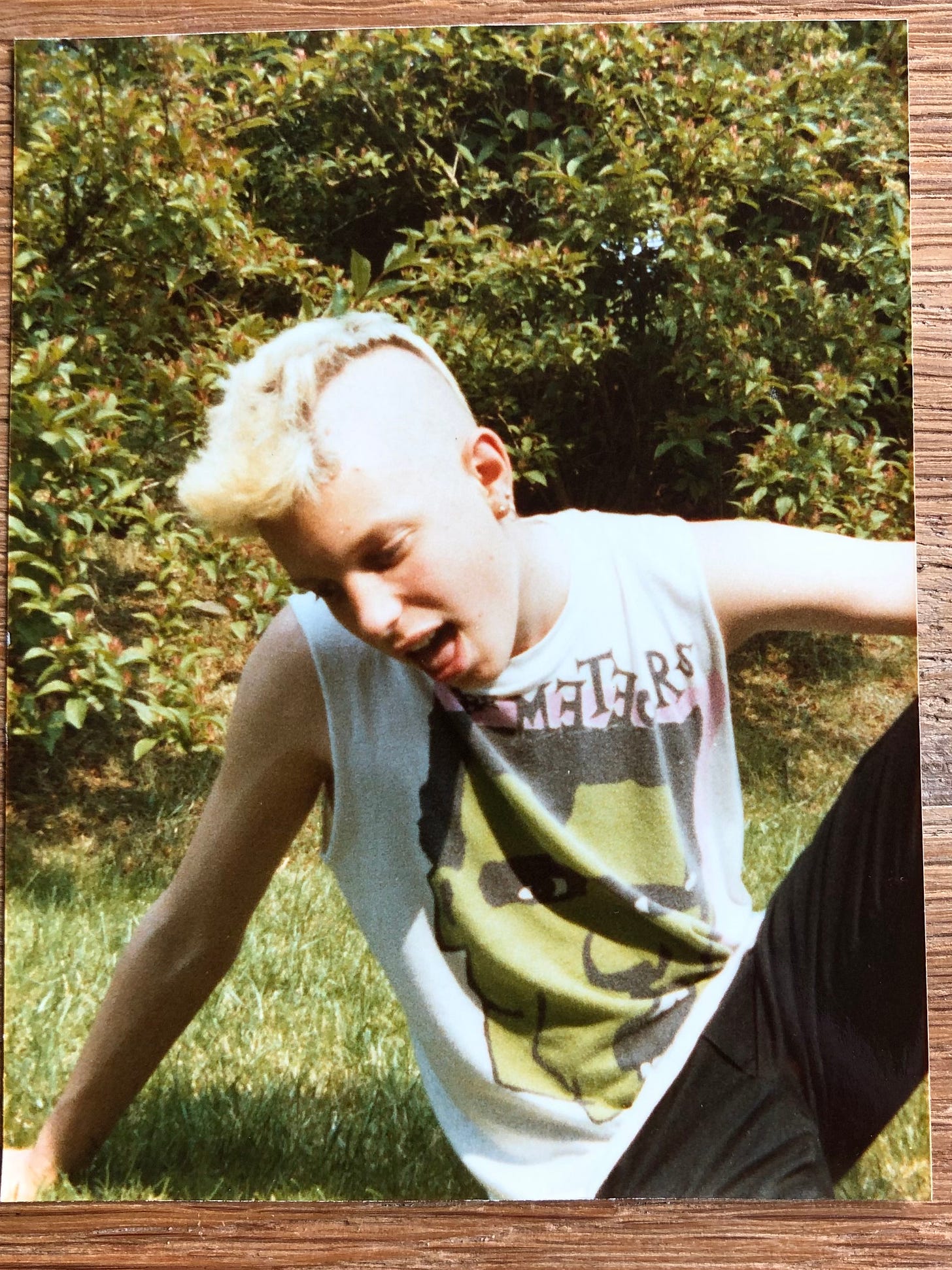

Bleached hair, grown out so that the roots are visible midway into a two-inch flat-top. Shaved bald at the sides and the back. Three earrings in the left earlobe. Green button-down shirt, short-sleeved beneath a cream 1960s sports jacket. Sta-Prest, black. Six-hole Dr Martens boots, black, rested upon the seat of the chair opposite, heading in a westerly direction after a day’s stomping around the city with Omar, Charlie and Teifion, leafing through record, comic and clothes shops, perhaps a little shoplifting, trying to avoid skinheads and the bored CRS police cooped up all day in vans. The typical Saturday afternoon after the Friday night before. I’d stayed at Teifion’s and I needed a wash.

At Puteaux a couple of likely lads catch my eye as the train flashes down the platform. They climb aboard and make their way down the carriage, sitting in the four-seater next to me. One is casual in tracksuit top and jeans. The other has a moddish skin vibe. He looks quite sharp, but I can’t really ignore the fact that he’s staring intensely at me.

‘Ça va?’ I ask, blankly, turning to face him. The kid smiles. He’s a couple of years older than me. I’d say around seventeen.

‘Ça va bien. Toi?’

I’m OK too, I tell him. He gives me a cheery thumbs-up.

Well, this is nice. I have been chased all over Paris and its many suburbs over the previous year or so. I’ve had a policeman smack me in the mouth for no reason other than walking into his teargas in the Métro as the CRS attempted to disperse Maghrebi kids in Les Halles. I’ve had a gang of black rockabillies – the notorious if unimaginatively named Black Cats – put me up against a wall in Clichy and frisk me at knifepoint, removing my wallet from my back pocket and, with some hilarity, the bent fork from my jacket. I even had a skinhead kick me from behind down a moving escalator at Oberkampf, before another then ripped the Harrington from my back. At a fairground in Saint-Germain-en-Laye some squaddies had followed us and then kung-fu kicked us in the parking lot until they realised that, despite our provocative hair, they were beating up children and wandered off, unsatisfied.

Nobody asked me how I was first.

‘Where are you from?’ asks one.

‘London,’ I say, ‘but I live here.’

‘Ah, OK,’ says the mod-skin. He sizes me up. ‘Is that where you get those Docs from?’

‘Yes.’

‘They’re great,’ he replies. ‘You can’t get them here easily.’

‘They’re cheap in England,’ I tell him. ‘Work boots. Everyone has them.’

‘Hmm,’ he says. ‘What size are you?’

‘43.’

‘Let’s swap.’

I look at his feet. He has massive old canvas army boots on, covered in stains. They look terrible.

‘No thanks.’

‘Come on,’ he insists. ‘French army boots, vintage. Very cool. It’s a cultural exchange!’ He starts unlacing his shoes. Meanwhile, his pal slides across seats and sits next to me. He punches me on the arm about as hard as you can when you’re friends with someone, maybe even a little harder. He nods at me. ‘It’s a good exchange. Fair. Take off your boots.’

I turn around, gazing down the carriage. There are a few people further down, in singles, looking out of windows or reading. There is no cavalry. I unlace my boots.

‘Merci mon pote!’ my new pal says, grabbing my Docs, then shaking my hand. His mate gives my head a massive congratulatory shove and stands up. We are pulling in at La Celle-Saint-Cloud.

‘You know what,’ says Mod-skin, ‘as you don’t really like my army boots, I’m going to keep them. OK?’

I shrug.

‘Salut!’ they shout as, laughing, they jump from the train. They walk by the window, waving my boots at me. I put my feet back on the seat.

At Saint Nom I walk down the platform in my socks and step into the phone box to call home.

‘Mum,’ I say. ‘Could you please come and pick me up from the station? I won’t be able to walk home.’

Adventures on the Metro playlist… Lost in music, 1982 through 1984

Chapter 3: The Last Of The Mohicans

Just a little off the sides, please...

The Last of the Mohicans extract:

Like a hair-shirted, middle-England Mafioso, Mr Pope slowly picked off my friends one by one. He didn’t like them, the way they behaved. The smoking, the earrings, the extravagant haircuts, the constant, unrepentant bunking off. Sta-Prest trousers and monkey boots. Mopeds. As headteacher, he expected better. So he expelled a couple of our group and sought assurances from the remainder’s parents that they’d be returning to England for good later in that summer of 1984. Coldly, he served his revenge.

He also inked in an appointment to see me with my mother for a similar conversation in April, just after the Easter holidays. By a stroke of luck, though, I managed to give myself glandular fever piercing my ears during a lesson with a much-shared stud earring and had to miss a month’s school after the break, prone and swollen on the sofa, watching well-worn VHS copies of Scum, The Godfather, Being There and various episodes of The Tube, transmitted in black and white because they were technologically mismatched with our French video player.

When I returned for the summer term, the expulsion storm had not only passed but, in my absence, an English essay I’d written for homework on the theme of ‘the countryside’ had been read out in assembly as an example of an English essay that was good enough to be read out in assembly. In fifteen long years alive, it was my first academic achievement – also the last.

Mr Pope soon invited me to a meeting in his office. I expected the worst. Immediately after my sick leave I’d been accused of dealing speed to other kids by a teacher, Mr Agnew, who’d received a tip-off from another student (the dirty rat). It was an outrageous allegation. I wasn’t selling speed. I was giving it away for free.

Unlike in England, anybody could buy ephedrine – an amphetamine – in French chemists, sold as small, round pink pills bottled and stored behind the counter, if you knew to ask. A kid from our village had hipped me to them. That year I always had a vial somewhere, particularly at parties where I’d gladly hand them out to all comers.

When nabbed with a bottle in my bag having been ordered to empty all my pockets in a classroom, I told Agnew that they were prescribed for my recovery from glandular fever – something to give me a little va-va-voom – and he appeared to buy it. This invitation to see the headmaster undercut that assumption.

I knocked on the door.

‘Come!’

I stepped inside the headmaster’s lair.

‘Ah Teddy, take a seat please.’

I sat. I loved the peace of his room. The deranged screaming of the kids on break in the yard below sounded like chicks softly clucking up here.

‘How are you feeling now? Fully recovered?’

‘I am, thanks.’

‘Good. Now, you may not know this yet, but while you were away, we decided it was time to launch an annual school magazine, edited by students and overseen by the English department.’ He paused to fiddle with some paperclips on his desk, raising his eyes to mine to address me. ‘You were volunteered to work on it, after your essay was read by Mrs Kennet in assembly.’

‘I was?’

‘You were. How do you feel about it?’

‘Alright, I suppose. Yeah, I’m happy to do that.’

‘Glad to hear it because you were nominated by Mrs Kennet to edit it, too. You were then voted unanimously by everyone involved to be this year’s school magazine editor.’

‘Shit! Sorry, sir. But, really?’ (I was clearly nominated editor because I was absent at the time of nominations.)

‘Really, yes. Do you want to do it? I hardly need tell you that this has saved your career at this school, as you were on the same knife edge as Chris, Teifion and your other friends.’

‘Yes, sir. Understood.’

‘Mrs Kennet spoke very highly of your English, of your essays. She said you were among the best English students she’s had here at this school. She convinced me of your promise.’ He didn’t look very convinced. ‘Don’t let us down.’

‘No, sir.’

‘She’ll be in touch about the start date. OK, you may leave now.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

I walked to the door, pausing as I placed my weight on the handle. For a moment I considered turning around and telling him the truth, that I’d copied much of my prize-winning essay from an Alan Sillitoe short story I’d been reading at the time. Instead, I stepped through the door and carried on downstairs to lunch break…

To buy Paper Cuts for a reduced price, use this link, quoting NEWCUE30

Wednesday: early experiments and explorations in music journalism…