G’day,

Don’t call it a come back! It’s just the second of our three-part Paper Cuts extracts extravaganza. And yes I am compiling this sleep-deprived and hungover in a heatwave, so if you spot any errors don’t blame me, blame Chris. That normally works.

Before we get into today’s extracts, let’s take a moment to raise our beakers in memory of Paul Ryder, the Happy Mondays bassist who died last week at 58. ‘Bassist’ seems too slim a description of his function in this most dynamic and original of bands. His bass was the sound that carried everything forwards, the grease in the Mondays’ wheels, the frame that held their music in the same place.

In the spirit of that, I’ve picked a Happy Mondays-related excerpt today, Our Man In Havana, which is all about various encounters I had with Shaun Ryder, as well as the impact the Mondays made upon 20 year-old me in 1988. I’ve also included Sonic Boom, who was the subject of my first, disastrous interview, along with chapter-related playlists for each (10/10, would strongly recommend).

If you enjoy reading these excerpts, please do make use of the exclusive offer for New Cue readers of 30% off the RRP of Paper Cuts. Just click this link, add Paper Cuts to your basket and then write NEWCUE30 when prompted. But don’t just take my word for it.

See you tomorrow for one final set of extracts. Thanks for indulging me.

Ted (and Niall and Chris).

Chapter 13: Our Man in Havana

Our Man in Havana excerpt:

Happy Mondays rearranged the terms and conditions of my existence. I had seen them play at Dingwalls in the autumn of 1988, the week that their second album Bummed came out, a couple of months after I’d returned from the summer of working the beaches in the South of France, and that was that. No way back. I’d turned twenty a month earlier. The perfect age, as it turned out. Old enough for autonomy, young enough to not have a clue. Blank. Bored. Full of beans. Ready for action. And it here it comes, James Brown’s Funky Joy Division People. I belonged here.

They only played for thirty minutes, but I signed on the line. Our interests were in sync. Maybe things were going to change anyway. We’ve all read the witness statements now. Maybe acid house was rewiring youth culture and maybe Happy Mondays were just the first physical embodiment of that regime change in band-form. The documentaries are there for all to view. The conclusions seem very firmly of that opinion. I just know that I went to see Happy Mondays in Camden on a rainy night in November and everything changed. It was my personal year zero. I’ve measured every subsequent band I’ve seen in the flesh against that night.

It’s hard to imagine, isn’t it, when you see them now on those TV sofas, on Gogglebox or Good Morning Britain, cuddly and giggly, joking about aliens and alopecia. Old. Goofing off, messing around, playing up for the cameras. Loveable rogues. Big men, out of shape. Last of the summer fortified wine.

In their twenties, though, on nightclub stages, singing songs about drugs and orgies, freaks and fannies. My lord. Advocating hedonism with such zeal it felt like a revolutionary cause you’d die for (some did).

I was there because I couldn’t stop playing their latest single ‘Wrote for Luck’ in the shop. It just went round and round and round. I wrote for luck, they sent me you…

And here I am. And there you are, Shaun Ryder, spliff in hand, hunched over the mic wearing a chunky-knit cardigan and brown cords, barking out rhythmic slang poetry, eyes closed, smile wide, love-and-violence floating in the air. Bez at his side, skin and bones and maracas, like a cartoon alley-cat from a yet-to-be-invented Pixar film, limbs on strings, the band cutting the most psychedelic, kinetic groove I’d ever seen performed by white Englishmen holding guitars. It was Chic, reimagined by inner-city Lancastrian pub pirates.

Happy Mondays didn’t look like a band. Jesus Jones, who were supporting, they looked like a band: rock hair, nice guitars, branding, matching shirts. Clean. Happy Mondays looked like the kind of men you saw through the steel fence at away matches making cut-throat signs at you. This isn’t a recommendation, of course, but it made a change. It seemed more relatable than the Melody Maker small-ads guitar-shop boys who normally trod the boards for your pleasure. All the band’s mates were on stage too, dancing, gurning behind them, demanding the audience throw coins on stage for an encore that never arrived. That could be you up there, you know. You aren’t that different. It’s not a million miles away. You wear high-street knock-offs as well, just smart enough to bypass the door policy, whizz stuffed down your sock.

Afterwards, minds blown, Jake and I walked the eight miles back to Chiswick in the drizzle. We’d missed the train and there wasn’t a night bus, but that was OK. We were already on board.

I became heavily involved in Happy Mondays’ limited recorded materials: the chewy Mancunian garage-funk of their first album, 1987’s Squirrel and G-Man, as well as Bummed, the sound of cold British towns having very hot times. Their music was glued to my ears. I stole the old 12-inchers from the record shop shelves, I cheered the new releases onto television like a victory in the cup away at a fancied Big Six club. Happy Mondays were very influential. Inspired by their freedom of expression, I quit my job and travelled on a six-week drug pilgrimage through Europe to Morocco. They were a revelation for hedonistic herberts everywhere, grotty outsiders who’d nevertheless snuck inside. They changed a generation’s wardrobe.

As I started writing about music, I wondered if I’d catch up in time to have some nights on the road with Happy Mondays. They were very funny on the page. I liked that, turn it up. I wanted to share a quiet moment with Shaun Ryder.

But they queered their pitch before I got within sniffing distance. Just four years after my first sighting Happy Mondays were done, cooked in their own bad habits – mostly Shaun Ryder’s – with the final nail in the coffin hammered by NME’s Steven Wells when he coaxed wretched homophobia from them during a cover interview to publicise their tired fourth album in 1992, after the hits from LP number three Pills ‘n’ Thrills and Bellyaches had pushed them over the good-times edge. They were kaput. They hated each other. They needed to get away. So they called it a day, sent in the lawyers and went for a Kit-Kat.

Farewell rainbows, hello grey skies.

*

December 1, 1995

As we were booked on a morning flight to Havana, it was decided that it would be prudent if Bez stayed in the Hilton attached to Stansted Airport. He could oversleep, jump out of bed at 8.45 and still meet us at check-in by nine a.m. that way. Safety first.

At 9:20, Anton Brookes, the PR nominally managing the trip, was persuaded by photographer Kevin Cummins that he’d better check Bez was on his way. Anton called the hotel.

‘Er, there’s no reply from his room,’ Anton reported upon his return from the pay phone. He looked around the airport, sweeping his long hair into a ponytail as he did so. ‘But he’s not checked out either.’ Sheepish grin. ‘So . . . what do you want to do?’

Anton was the archetypal gentle giant. As huge and as physically intimidating as a rugby league player, but as softly waggy and easily distracted as a golden retriever. A kind, empathetic Yorkshireman who drove all journalists mad when they needed him to produce the goods. Despite that, I loved seeing his big grin come bouncing around the corner – that baked-in charm was no doubt the secret of his success.

He also did press for Black Grape, Shaun Ryder’s new group which included rapper Paul ‘Kermit’ Leveridge and Ryder’s long-term foil, the dancer Mark ‘Bez’ Berry, as members.

Improbably, Ryder had pulled himself free from the wreckage of debt and heavy drugs which surrounded Happy Mondays upon their demise. With the help of American producer Danny Sabre and a new group of session players he delivered Black Grape’s upbeat party manifesto It’s Great When You’re Straight… Yeah. I was handed it to review for NME at the end of July 1995 and gave it a gushing, ten-out-of-ten full-page lead review. It was exactly what I’d been waiting for ever since Bummed. I thought it was brilliant. I wasn’t alone. The album’s druggy funk entered the charts at number one.

Soon after, Anton suggested an NME cover story with Black Grape could take place in Cuba. As Ryder was prevented from entering the US on a work visa at that time due to historic drugs convictions, Black Grape thought it would be amusing to invite MTV and assorted interested American publications to Cuba for the band’s round of US publicity. Communist-ruled Cuba, of course, was on the banned list for American citizens. The American journalists would have to travel via other Caribbean islands and not disclose their full itineraries to US immigration. I’d been recently made staff writer, so I was commissioned to tell the story for NME.

The fly in the ointment of this practical joke was that the band themselves had to make it to Cuba. Black Grape were all travelling from different locations. Shaun Ryder was coming from Mexico, where he was on holiday with his fiancée, Oriole Leitch, daughter of sixties folk superstar Donovan. Kermit was flying from Manchester. And Bez was coming from Stansted with us, to make sure he arrived. Except he wasn’t here.

Kevin Cummins, the only real adult involved in the whole enterprise, told Anton he should call Black Grape’s management to find out what was going on with Bez. Anton agreed with him. Presently, he returned with more bad news.

‘So,’ he began, grinning ridiculously. ‘Nobody’s heard from Bez.’

Right. Massive, gaping pause.

‘And Kermit’s in hospital.’

‘What?! What’s wrong?’

‘Dunno. But Shaun’s definitely on his way! He’s leaving this afternoon. He was meant to arrive yesterday but he’s had food poisoning in Mexico.’

‘So we’re still going?’

‘Everyone’s looking for Bez. At worst you’ll still have Shaun in Cuba.’ Big grin. ‘Hopefully!’

Kevin rolled his eyes at me. He’d shot Happy Mondays many times, most famously taking the photo of Ryder hanging from a giant letter E on the roof of a hotel in Spain for an iconic NME cover at the height of the Mondays’ powers. He was used to their shenanigans.

‘That’s reassuring, Anton,’ replied Kevin, dripping with soft Mancunian sarcasm.

Ninety minutes later, our Cuban Air DC10 was bouncing its way through the clouds as the pilot clicked off the seatbelt signs and the cabin crew made their way down the aisle with complimentary rum.

While Kevin and I said cheers, Anton unclipped and bumped off the seats along to the facilities. Kevin immediately leant across the aisle and rooted through Anton’s hand luggage, gleefully removing a lingerie magazine. Shaking his head sadly as he leafed through, Cummins opened it upon the centre-spread and lay the magazine across Anton’s seat-table for all to see.

I turned to face the window, bringing the rum to my lips as we fought to hit altitude. The flight was choppy, but worse turbulence surely lay ahead on land.

Our Man in Havana playlist…Shaun William Ryder, from 1987 to 2021

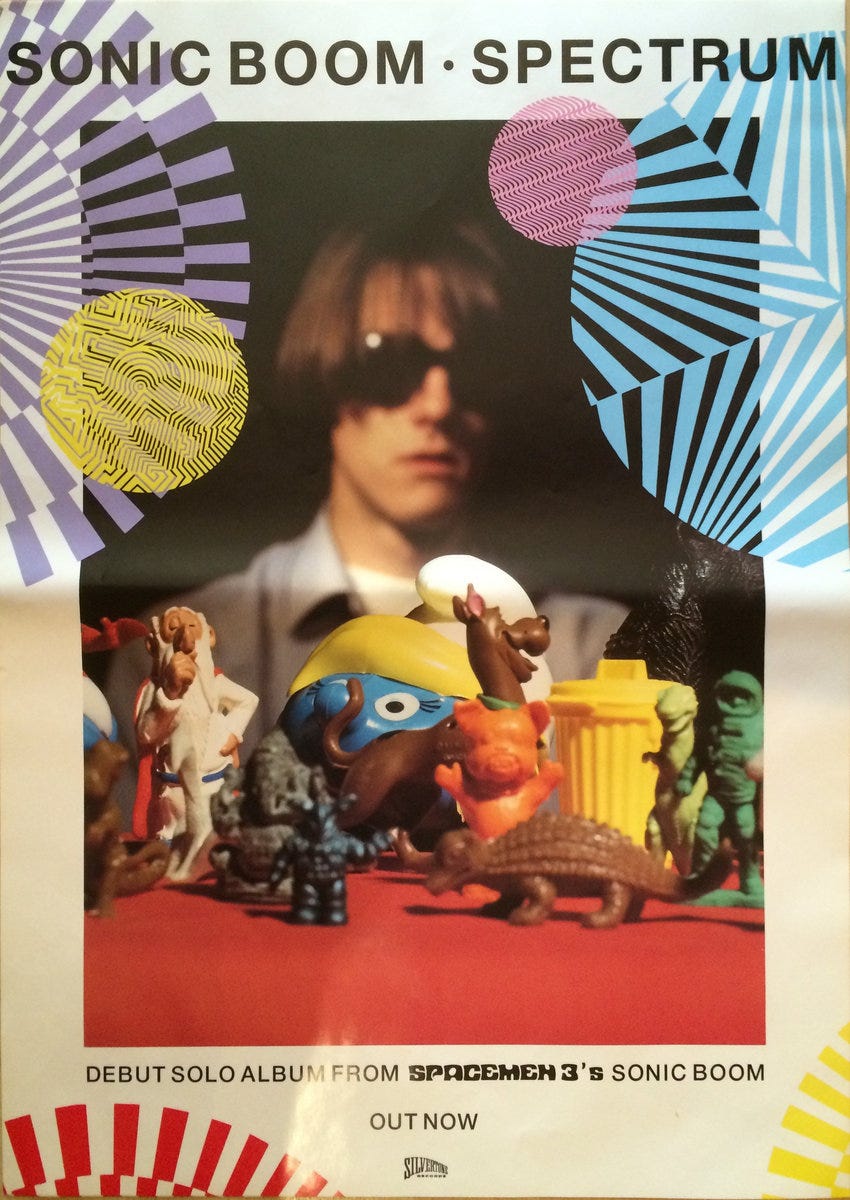

Chapter 7: Sonic Boom

Sonic Boom excerpt:

On the train to Rugby, Oliver gave me a pep talk. You only need to interview him for forty-five minutes and then write around a thousand words. There’s no rush to get it in, either, because the magazine is being run out of a flat in Highbury by an American woman with a load of pet lizards, a labour of love, and it’s ready when it’s ready. Just write it in the next few weeks. There’s no money, but just think of the glory.

Pete ‘Sonic Boom’ Kember met us at Rugby station in his fancy fast car, a live Happy Mondays recording blasting out of the tape deck as he zoomed into the pick-up zone. He yanked open the door and told us to get in. I settled next to him as the electronic bass of ‘Hallelujah’ rattled the dashboard and he shouted at me, ‘Do you like the Mondays?’

I’d taped this same concert from Radio One a couple of weeks earlier, but that story seemed too long. I nodded. I loved them.

‘Good, good,’ he shouted, turned the volume up and off we sped towards his parents’ house, Kember singing along to the choruses and laughing knowingly at Shaun Ryder’s adlibs. ‘I’ve seen them loads,’ he said. ‘Best band in the country.’

The car crunched over gravel as we rolled inside the gates of his parents’ home. It was a mansion. He climbed from his motor and made a dash through the afternoon into the house, bounding upstairs beyond the double-fronted entrance hall four steps at a go. We’d be talking in his bedroom. Tea?

Pete Kember had the physique of Jeremy Irons and the philosophical self-confidence of every public school bad-boy you meet at full-moon parties or drug dependency units the world over. A lovely bowl-cut, centrally parted. Button-down shirt under a blue crewneck, light denim jacket, black jeans. Desert boots. An MC5 badge. He gestured towards a beanbag and pulled up a small chair, slipping Link Wray on the turntable first. His room was painted a powerful red and upon the walls were framed prints of Warhol’s Marilyn, Lichtenstein’s Wham!, posters of Bo Diddley, Panther Burns, the Cramps. I noted the Cramps poster and described seeing them in 1984, when there was a riot in the audience at L’Eldoraldo in Paris. Seats were ripped out of the upstairs balcony and used as missiles on those below, as a local dispute between skinheads and rockabillies was settled. The next night singer Lux Interior came on dressed in just a pair of black leather underpants, holding a lime green umbrella over which he proceeded to pour a bottle of red wine. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, last night we fought,’ he told us. ‘Tonight, we make love.’ Then he unzipped his pants and let it all hang out.

This tale broke the ice. For the next half hour or so, Kember and I chatted about records we liked as Oliver took photos of him. After a while, I relaxed in his presence to the point where I felt emboldened enough to ask if he minded if I rolled a joint. OK, he said. Go ahead.

I took a small lump of hash from the inside pocket of my jeans, unwrapped it and put my lighter to its edge.

‘Woah,’ said Kember. ‘Let me have a look at that.’

I handed it over and he took a bite of it. He chewed it for a moment, then spat it on the carpet with disgust.

‘That’s shit mate,’ he said, decisively. ‘You can’t smoke that rubbish in here.’ He put it on his bedside table and removed a box from his drawer. He produced an eighth-of-an-ounce-sized square of golden-brown hash from it. ‘Here,’ he said. ‘Moroccan, freshly arrived. Good stuff. Use this.’

I took his slab and rolled a joint as he inspected my handiwork in progress. I did not falter. This was the day’s one task that I had rehearsed sufficiently. I lit it and passed it to him, but he raised his hand.

‘OK,’ he said, ‘let’s do this interview now.’

‘Oh, I thought this was the interview?’

‘What?! No. No. This is just fucking nothing small talk.’

I stared at him blankly. Not only was I in uncharted territory, I was also now a little stoned.

He started to talk to himself, loudly, but looking at the floor in exasperation. ‘I told them about just sending me amateurs, I’ve got too much to do.’

Oliver leapt in. ‘Why don’t you tell us about your new album, Pete, where it came from, and Ted will start recording.’

‘Oh,’ I said, gesturing to the mini-Dictaphone I’d borrowed for the day, ‘I’ve been recording the whole time, it’s cool.’ (It’s cool?)

Pete Kember shot me a look, but facing back to Oliver started to describe with great eloquence his first solo album, Spectrum, which had been released to middling appreciation a little earlier in the year.

The world was waiting for the final album by Spaceman 3 – his real band – that was due sometime soon. But he and his songwriting partner in Spaceman 3, Jason Pierce, were no longer on speaking terms. A few weeks earlier Kember had announced he was actually no longer in Spaceman 3, as he was affronted that all of the members other than he had released a single together under the name Spiritualized, with a sticker on the sleeve that read Spaceman 3. The tail of the dispute was long. It had its roots in money, ego, comedowns in confined spaces, women. Or, specifically, Jason Pierce’s girlfriend Kate Radley, who Kember felt was intruding on their own creative bromance. There had been dramatic disputes in splitter vans over the last couple of years, punches thrown in management offices. It was a bad scene.

Lots of great material there to get stuck into. Instead, I asked how the Spaceman 3 album was coming along.

‘It’ll come out,’ said Kember tersely (and accurately: it arrived in early 1991). ‘I’m doing one side and he’s doing the other.’

Suddenly and dramatically the front door slammed.

‘PETER?’ called a clear, crisp, upper-class voice. ‘ARE YOU HERE? WILL YOU BE EATING SUPPER?’

Fuck. Kember stood up, opened his bedroom door and called down from the landing. ‘I’m just doing an interview, Mum.’

He returned and sat back down. Shall we wrap it up soon? No problem, no problem at all. I put my stuff away and stood to leave. Pete Kember picked up my lump of hash.

‘I can’t see you leave with this shit,’ he said. He handed me his lump. ‘Take this instead. I’ll give you a lift to the station, there’s a train just after six.’

I thanked him for his generosity, given the circumstances. Down the stairs, into his car, speeding through Rugby towards the train, Happy Mondays’s Wrote For Luck alerting all of Warwickshire to our approach.

Sonic Boom playlist…Lost in music, 1990 through 1992

To buy Paper Cuts for a reduced price, use this link, quoting NEWCUE30