Good morning,

It’s Monday and Mondays are generally rubbish but we’ve got just the thing to catagorically un-rubbish your Monday. That thing is today’s edition, that you are reading right now, in which we speak to Rick Buckler from The Jam (and From The Jam) about his new book documenting the final year of the band (The Jam that is, not From The Jam). It also contains some previously unseen pictures of The Jam at their peak. Because we are nice and we care about everyone on our mailing list, even the freeloaders who get to enjoy our award-winning Monday content for nothing, this is a free edition. You’ll need to be a subscriber for access to Wednesday and Friday editions though. You can do that with one click below. It’ll make us happy. You want to make us happy, don’t you?

Enjoy the edition,

Ted, Niall and Chris

Start The Week With…. The Jam’s Rick Buckler

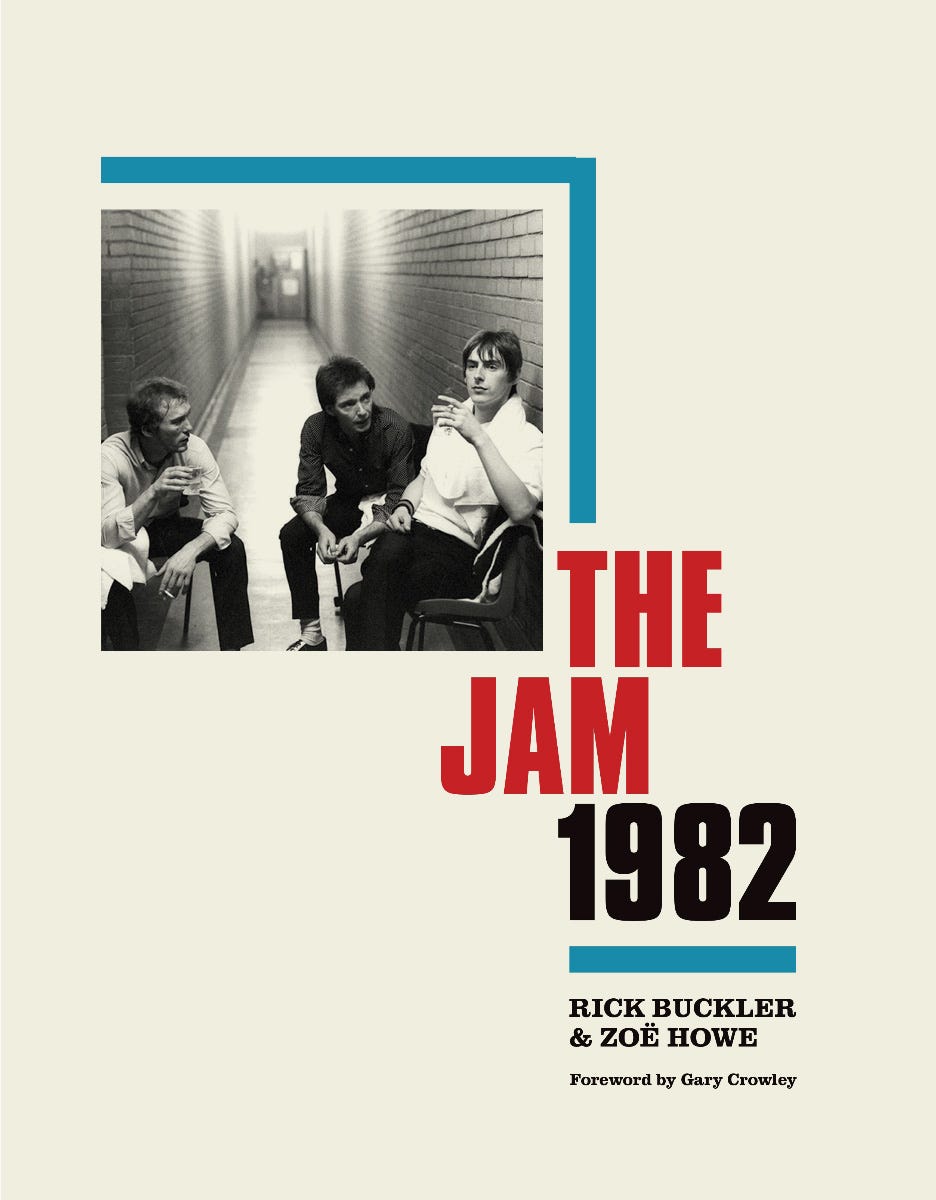

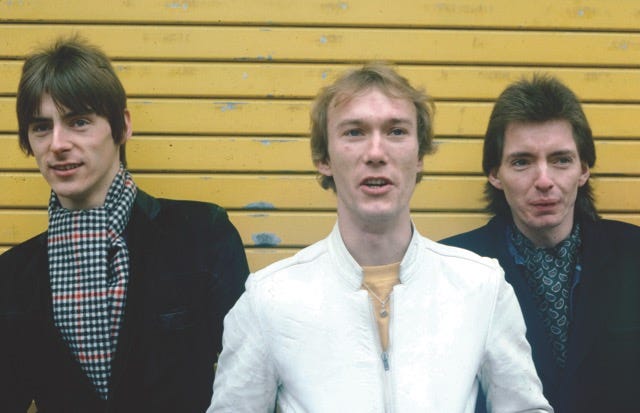

When Paul Weller decided to break up The Jam at the peak of their powers in 1982, he may have cemented the group’s legacy as the UK’s most consistently brilliant band of the era. He also broke the hearts of thousands, however, not least Jam drummer Rick Buckler who, alongside bassist Bruce Foxton, found himself without a job after ten years in the band. Written by Buckler and author Zoë Howe, The Jam 1982 is an illustrated oral history of the band’s final year, featuring contributions from Gary Crowley, producer Pete Wilson, Paolo Hewitt, Eddie Piller, Suede bassist Mat Osman and more.

Chris called up Rick a few weeks ago to ask how the book came about and how he felt about the band’s split 40 years later. Seeing as the book is focused on 1982 and the end of The Jam, why not have a bash on their evergreen final album, The Gift, while you read…

What was the idea behind just covering the final year of The Jam?

Well, it’s been 40 years since Jam split so the publishers thought it would be a good idea to cover just the one year, 1982. I must admit I found it difficult to do because it was an emotional year for me, as I’m sure you can imagine. But once I got my head around it, [it was OK] because it shows all sides of what was actually going on at the time, from the inside and the outside. I think Jam fans probably find something new in there that hasn’t been written about before.

You wrote your autobiography, That’s Entertainment, a few years ago. How different was this experience for you?

When I did my autobiography, I just really focused on all the great things that happened with the band and what we achieved and that sort of thing. But this time around covering just ‘82 you can’t avoid the fact that Paul pulled the rug out from underneath the band, so it does really deal with that. I wanted to write it because there’s a lot that’s been said over the years about what went on in that final year and from my point of view, I wanted to say it like it was as I experienced it.

Was it still difficult for you to revisit that period after all these years?

For myself and Bruce, with the work that we put into the band, to suddenly find out that Paul wanted to call it a day was quite devastating. The initial news was quite shocking. One of the things that annoyed me was the reasons for splitting the band up didn’t make sense at the time. We didn’t fall out, we were still successful, we were still selling records and doing great shows. All the logical things that ring the death knell for most bands weren’t affecting us. The initial reason that Paul gave us was that he wanted to get off a treadmill that he felt uncomfortable on. But that didn’t make sense, either. Because it was a treadmill that we’d fought for five years to get on. We fought so hard to get ourselves on this treadmill and to stay there and be successful. We did try and talk him out of it, but he’d made his mind up so that was that.

There’s some fantastic photos of The Jam on tour in the book. You don’t look like a band about to split up…

Yeah. We invited Twink [photographer Neil Tinnings] to come along and take some shots on the road. Twink got stuff nobody else got access to. It was lovely to go through some of those. They evoke so much. The one on the cover for instance, we were backstage literally discussing what songs we were going to play for the encore. I love that shot. It was nice to phone Twink up and see what other stuff he had. He put a lot of those photographs in a suitcase under his bed for years so that was a bit of a discovery. It was nice to find something fresh, because most photos of The Jam have already been seen.

One of the things that comes across in the book is how after Paul told you and Bruce he wanted to leave, the three of you carried on as normal for the rest of the year, recording songs, playing gigs and working as hard as ever, almost as if it wasn’t happening.

We were grown up enough to realise that if any one of us wanted to leave the band that that was their decision. We were all adult enough to respect that decision and work out a way of getting through that last year and fulfilling our commitments with the record company and the promoters and the things that we’d already committed to doing touring-wise. It was all quite gentlemanly. We just got on with it, really.

What do you recall of that meeting?

We’d booked ourselves into the studio to record three or four songs. We got there and Paul made the announcement. We had a conversation about the ups and downs of what he had just told us, and then we simply got on with the recording. It was the most bizarre feeling.

Were you in shock?

It did sink in slowly. I think I felt that it could have been one of Paul’s kneejerk reactions to something, but I suspected it probably wasn’t. We were very professional in the way that we went about things. We always turned up. If we had some work to do, we simply got on with it. But I did think that maybe Paul would change his mind. The final shows were great, so we thought we were going to change his mind, ‘Surely, you can’t be throwing this away…’

When did it finally sink in?

It never really sunk in until I woke up in 1983 and realised I had no reason to get out of bed anymore. For the past ten years, everything that I did had revolved around the band and all of a sudden it wasn’t there anymore. It was like a void that I’d stepped into. It was a bit strange for the first few months of 1983, but you just have to get on with your life. It still annoys me that Paul gave it up for something like The Style Council because I’m not a big fan of The Style Council. I really can’t see how The Style Council was a step in any sort of direction that was any better than what we had in The Jam. But there again, that’s just a personal thing. Obviously, some people did like the band. But that’s a view that might be tainted by what was actually happening.

Did you have much contact with Paul and Bruce after the split?

I thought that we would all still carry on as friends as we still got on quite well together amongst ourselves. Every year before Christmas we always had a little Christmas party and even in that year we still did one after the last show in December. I thought that I would always stay in touch with Paul but that evaporated quite quickly. I did one thing with him when he needed somebody to do some percussion on a track. I went along to this recording studio and did it, but I found the whole atmosphere very strange. He was asking me to do the most ridiculous things, quite demanding things. I thought, ‘You know, that’s not really my sort of remit to do this sort of thing...’ But I did it in any case. I thought it would be nice to be able to sort of stay in touch, but it was very difficult. Both myself and Bruce tried to stay in touch with Paul, but he didn’t really want to know.

The book starts just before 1982, in the winter of ‘81 when you started work on what would be the final Jam album. Did you feel at that time that Paul was wanting to move away from The Jam sound and explore something new?

We always tried to approach things in a different way and for the band to move in a slightly different direction. If you look at all the albums, they’re all different one to another, we never rested on our laurels, we were evolving and doing all sorts of different styles and trying to push the envelope. We weren’t scared of experimenting and doing things that we wanted to do. So we weren’t in a rut musically. I think we were always open to new ideas and new ways of doing things. So the idea of musical differences, Paul never brought that up, but that wouldn’t have had made any sense either. There was definitely something going on in the background which we were unaware of. Who can say, it’s a bit of a mystery. As I say in the book, to say that the reason for splitting the band up was to make it mean something… I just don’t see that. I don’t think it holds a lot of water.

When The Style Council came out could you see yourself and Bruce making music like that with Paul?

A lot of those songs we had actually rehearsed as new material for The Jam, but never really recorded. But it certainly didn’t come across like The Jam, it didn’t have that drive that myself and Bruce would have put behind it. Also, Paul putting down the guitar and just wanting to be a singer. You get so used to seeing someone with a guitar round their neck. Those Val Doonican jumpers that appeared on the scene and the funny haircuts and stuff like that. It was what he wanted to do and was the direction he wanted to go. I remember Bruce telling me that if that was the direction that The Jam was going to turn out like then he would have left.

If neither you nor Bruce particularly liked what Paul was doing with The Style Council, did that soften the blow at all? You could look at it and say, ‘Well, that’s not really my cup of tea so maybe it was for the best…’

No. I think we would have probably evolved in one way or another along those lines but without that sort of fashion thing. Because he changed his whole fashion. His haircuts and clothing and everything moved away from the mod thing. There was definitely a shift, but it wasn’t my concern. I think it’s a shame that The Style Council didn’t move on and do anything, in my view, better than The Jam. But that’s just my personal view. I know there are a lot of people who are fans of The Style Council.

It was a difficult time for you, but do you also have some fond memories of that final year of The Jam?

For me, playing the live shows. The shows were really good, they were probably the best shows we did in the UK. We always gave it 110%. You’d go up on stage and just go for it. Every single gig seemed to last one second. It was full on. You’d walk off stage and go, ‘Whoaaa, what was that?!? The excitement never went away. That was still great fun. it was still very, very enjoyable, right up to the very end.

Obviously, you wanted The Jam to carry on, but other than The Beatles you were pretty much the only band to ever bow out at the top of your game. You never made a bad record or sullied your reputation like some of your contemporaries ended up doing. Can you look back at it now, forty years later, and in some way appreciate that you left a perfect legacy behind? Not a lot of bands can say that.

Yeah, there is that, but I think that’s something that’s purely come in retrospect. I don’t think that’s an argument for why the band should have split up. When we started out, we didn’t go out of our way to create a legend or anything like that, but it is nice to look back and think that the band meant so much to people and that it still does, both to the people who were there back in the day and who have discovered them since. I think that’s absolutely fantastic.

Photos by Neil ‘Twink’ Tinning

The Jam 1982 is out now via Omnibus Press and available to buy HERE.

CC