Hello,

Welcome to your Monday edition of The New Cue. Today, we have a mammoth pow-wow with Britain’s last great underground musical visionary, Lawrence of Felt, Denim, Go-Kart Mozart and now Mozart Estate. Have a listen to his incredible back catalogue while you read, if you’d like.

We won’t take up too much more time up here because there’s loads to read below. But if you enjoy it, then please share it, tell your friends and subscribe to this newsletter for more of this gear twice a week, every week (closed at Christmas). If you do like it, then Lawrence and Ted will be chatting again this Friday evening on stage at Rough Trade East. It’s free.

Enjoy the edition,

Ted, Niall and Chris

Start The Week With… Lawrence

Lawrence takes all business meetings at a coffee shop opposite his block of flats on White Cross Street, the cosy market road that lies between Old Street and Liverpool Street in central East London. I’ve interviewed him a few times before.

The first time was during the second summer of acid house, 1989, as he bid farewell to ten years as the singer and principle songwriter with one of Britain’s greatest underground groups of the decade, Felt. We met on the steps of The Royal Court in Chelsea, in blazing sunshine, before heading in baggy denim to the roof of his nearby studio flat to hear how he’d finished with indie life. He’d made ten albums and ten singles in ten years for his favourite independent labels, Cherry Red and Creation. The first five years were sketched in partnership with the distinctive guitar prodigy Maurice Deebank, the next five in partnership with the distinctive keyboard prodigy Martin Duffy. They’d made romantic, abstract indie-pop; they’d made melancholic piano ballads; they’d made a variety of instrumentals, from organ-based to jazzy vibes; they’d made the archetypal 1980s underground anthem Primitive Painters that somehow nestled just outside the Top 40. Now, Lawrence had mapped out a future as a huge mainstream pop star, signed to major labels.

Two years later we met at his new flat on Endell Street in Covent Garden. His first album as Denim was about to be released. Back In Denim was an indisputable masterpiece, marrying memories of his life growing up outside Birmingham in the 1970s and modern manifestos with a sparkling contemporary pop-rock sound. The songs were brilliant. Middle Of The Road is one of the all-time great debut singles.

It flopped commercially, as did the album. In 1996, I interviewed him again, around the great second Denim album, Denim on Ice, at his London Bridge flat. Another great record, another commercial disaster.

We last met in 2018, at this very coffee shop, to talk about his fourth album with Go-Kart Mozart, the “B-side band” he’d formed to take the pressure off his songwriting. Then, as now, we met at the cafe so he could grab a tea, have his daily morning cigarette and so I could tap a kidney without the need to use his toilet later. Then, as always, we’d head back to his flat, the same one that featured in the magnificent 2012 documentary about him, Lawrence of Belgravia.

He’s never been late before. But today, as the January sleet washes the EC1 streets, he’s an hour overdue. Suddenly he appears, breaking into a shuffling jog as we catch eyes across the street. He’s very apologetic.

“I was actually early,” he claims. “So I sat down waiting for 10:00 am and just closed my eyes. Next thing I knew, it’s 10:45!”

Before we go anywhere, I offer my condolences for his old Felt colleague and friend Martin Duffy, who died after a fall at home just before Christmas. It was shocking news. “I know, terrible. He banged his head and just died. What are the chances? I was so lucky to have worked with him for so long. He was a teenager when he joined Felt and he was an incredible keyboard player, just amazing. A teenage prodigy, a real one. His family are Irish and they were all really amazing musicians. He could play anything just off the cuff. I had him on keyboard, and before that Maurice [Deebank] on guitar. Just amazing, really, to have worked with two teenage prodigies. That’s what I’m looking for next. I’m looking for another teenage prodigy. They just have something different.”

We gather up our drinks, stub out our cigarettes and head up to his top floor flat. “I still haven’t finishing decorating,” he says, as we step from the lift. “I know! It’s been like six years…”. It’s been over a decade. “Don’t tell me that. God.”

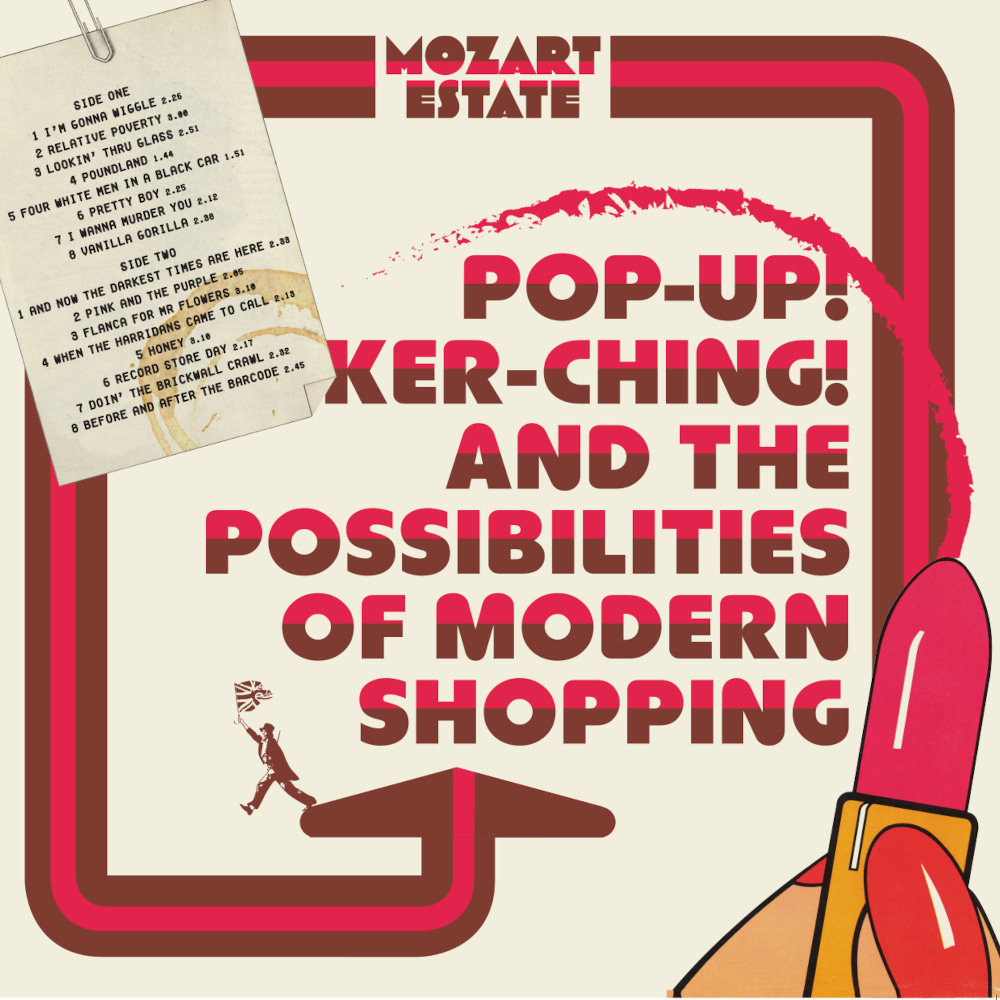

Then we sit in his unfurnished bedroom, as the rain lashes the windows, to discuss all aspects of Lawrence-world, most notably his new album Pop-Up! Ker-Ching! And The Possibilities Of Modern Shopping by his renamed Mozart Estate. The album is out this Friday on West Midland Records, via Cherry Red.

How have you been?

How have I been? No more sex, no more drugs, not much rock and roll. That's my summary of Christmas. It's been so boring. Really boring. I'm going away next year. I want to go on a cruise, a cruise on my own. I do want to go somewhere...Not hot, so not to the Caribbean. But somewhere on a boat so I am confined. And just miss out Christmas all together. I can't bear it any more.

There are cruises that go through the fjords of Norway.

But then again, I don't want to be too cold. It's hard. I'm looking into it. I'm definitely going away. Because it’s so dead round here. I’m in this area, which is really alive and bustling. And at Christmas, everyone shuts down. I’ve been really bored at the moment, waiting for things to pick up again.

The first person in history to die of boredom.

I will be! I told you.

How's the pandemic been for you then?

It's been the worst two years of my life.

I spoke to a lot of people who wondered how you were getting on during it. We couldn't really imagine lockdown Lawrence.

Gosh, it was so awful. I took no notice of it. I carried on walking every day. I found one cafe that was open in Bethnal Green. So I would walk east to this cafe to have a cup of tea. One day I thought I can't, I'm so tired. I wonder if I'm allowed to go on the train to Stratford? I went to the station and there was nobody about but it was all free. So I started going on the train. I went out nearly every day travelling all around and there was nobody on the trains, nobody on the buses, there were messages all the time saying 'you must not travel if you're not a key worker'. So at first I was a bit worried, but then I carried on as if nothing was wrong. I tried to go in the studio but they wouldn't open, they wouldn't risk it. So I couldn't finish the album off. I was travelling around the outskirts of London. It was awful. It really was like a film, a nuclear apocalypse film. There was nobody around in the suburbs. Nobody. I didn’t see people for days. Then occasionally you'd come to an area where there'd be a supermarket open, it was like a mirage. I don't know how I got through it, honestly. What about you?

Well, Q folded at the start of it because of the pandemic.

That was the final thing?

That was the final thing. The shops weren't open so we couldn't sell the issues.

I wanted to carry on doing stuff but I couldn't. So I went out, but there was nobody out. London Bridge station, which I was using, was absolutely dead. Unbelievable. And when it started getting full again, it was such a hard thing to get my head around. I'd got so used to nobody being around. Everyone took it seriously didn't they? I thought there was going to be young people who'd just say no to it. They’d be having big discos and parties in warehouses somewhere, but they didn't. Everyone was really scared. They really frightened us into submission. But I carried on. I took no notice. I didn't wear a mask for ages. Then in the end, I liked wearing the mask because nobody could tell how old you actually were.

That’s a positive.

The one good thing to come from it.

So what's the fundamental difference between Go-Kart Mozart and Mozart Estate?

Mozart Estate is more serious. Less frivolous. I suppose it's reflecting the times that are more serious. It's a good time to change the name. I wanted Go-Kart Mozart to be a quick three album project in the beginning, but it's gone on for so long. And I didn't like the name, which was meant to be disposable, being like a name for a proper band. I liked it as a project. As it went on, I thought, that's too long. This was a good chance because the music was different on this one, for me. I finally learned how to produce a record properly. So the songs sounded different. The production was different. I thought, Oh well, I'll use this new name. I like the novelty aspect of things with Go-Kart, but I didn't want it to be a career. I don't want people to think, Oh yeah, he used to be serious, now he's not. I didn't like that connotation. I've always been serious about the music, but Go-Kart Mozart sounds like a novelty band.

The words in Go-Kart Mozart could be funny, but there was still some really serious stuff: A Black Hood On His Head, When You’re Depressed, Plead With The Man…

I was always serious about it. But I think the name lent it a sense of, Oh he's gone. He's changed from Felt, he's really changed. Mozart Estate, Felt, Denim just work together. Mozart Estate: a serious name for serious times.

Last time we spoke, in January 2018, you said “I’m making a singer-songwriter album next, totally stripped back, really direct, really personal. Guitars again. The complete opposite to Go-Kart, that’s for certain.” What happened?

I'm still working on it. I've got the songs. And once this project is complete... Because we went on the road, and it's a really good band, we had great musicians, and I want to see it through to the end, really. So now this is the end of the project, for sure. Then I can do something different. I mean, it's not like it’ll end next week, we'll finish this run. Hopefully, it will take a year to promote this album. Then we’ll do something different. I still might play Mozart Estate gigs, but I might just do something in tandem. I'm not gonna say I'll never play Mozart songs again. But I want to do a different project with a guitar, bass, drums.

But you never play old songs.

No, but I will play Mozart Estate songs. I might keep Mozart Estate in tandem with another idea. Because it's nice to play those songs. It's nice to play Mozart songs live. I'm not gonna say, like we did with Felt, this is definitely the end. I'd like to move on from Mozart, do this more introspective record. Hopefully it can be a live project, but I’ll still do the Mozart thing live. I'm not just putting it all to bed, because we've got great songs that work live, like Relative Poverty. It's a good show now. I can interact with the audience. I don't want to throw that away, do something really serious where it's more stand-offish. With Felt there was no interaction at all. None. It was a Dylan thing, Tom Verlaine. It was as if the audience isn't there, you just do what you do and that's it. You don't take any notice of the audience. I mean, you do, but you don't really show it. You just play your music and that's enough. But with Mozart, you can interact with the audience, and you understand whether they like it or not. They usually do. I don't want to throw that away. But musically, I want to do this singer songwriter thing, if I can find a guitar player, a teenage prodigy. That's what I'm looking for.

So we're putting a call out for a teenage guitar prodigy.

Yeah, we are. Send out a signal with The New Cue.

Last time you also mentioned a Christian rock album you’d written: Jacob, Abraham, Noah & The Other Cats In the Bible.

It's there. If I ever make loads and loads and loads of money, I can do it. I haven't got the resources to get it together. It’s got to be high-end. No corners cut. I've learned from Go-Kart Mozart that I'm not doing any more laptop stuff. I was forced into that position where I had to do stuff at people's houses. I hate it more than anything. It doesn't suit me at all, doing laptop stuff or doing a song in someone's bedroom studio. I can't bear it. It is the worst thing I've ever done. That's why I'm gonna go back to those Go-Kart Mozart songs and take them to a studio, remix them and redo various parts and make them proper songs. Because they're not. They're like demos.

Is it that you don't like the feeling of being in someone's bedroom doing it?

No, it’s not that...well, it is that because it's not like going to work. It's not like being in a band. It's amateur. It's amateur hour. I can't bear amateur, I don't like it. I made this new Mozart Estate record in a real studio. It's such a joy to do the whole thing in a proper studio around the corner, in Hackney. That's why it sounds fantastic. Sounds great. Have you noticed that? It sounds tip top. A lot of the other stuff was done at home studios. When you're there you think, oh yeah, that sounds great. Then once it's pressed up on vinyl you suddenly realise what’s wrong with it. Oh God, that's a mistake, that’s off - you suddenly realise all the things you did wrong. I simply don't like going to someone's house and recording in that way. It's not real. I know I said Mozart was a B-side band, but I could have done those B-sides in a real studio.

The B-side concept freed up your writing.

I found this amazing thing by Paul Weller. He says 'I suppose it's that thing of not caring too much when you go in to record a B-side'...That’s what I said years ago... 'Just being like, well, I've got this little rough idea, let's just go and try that. Often because of that spontaneity you come up with the best stuff. There’s a certain amount of freedom, because you’re not focusing on having to be on an album or fitting into anything you take more chances. It doesn’t seem to have that much importance, but often they turn out to be some of the best things.’ The most amazing quote. That’s exactly what I was trying to do with Mozart.

How did you record the new album, what was the process behind it?

We have the song done in a home studio, a demo, and then you take it to the real studio, and then you begin building it up. Like what I thought an Eno record was when I was a kid. He's in the studio, and he's bringing people in, and they're building it. And then people go home and you work on it with the engineer on your own. It's like that, really, all the records have been kind of like that. But this was the first one which is all in the studio. I made it with about ten or eleven people on it. So it's the live band, you know, Terry Miles and Rusty, the drummer, Ralph… and then there's nobody that you've heard of. A lot of them are new people. I'm like the boss. It takes ages, costs a lot of money. I had a really good deal with the studio, otherwise I wouldn't be able to do it there. He wanted me to work in his studio. So I was very lucky. It was very, very cheap and so I was able to just go over a couple of years. It wasn't like a band playing together, though, which is what I'm going to do next. I can't work in this way again, it just goes on forever. I want to do it like in Felt. We would rehearse in a bedroom, then we'd go to a rehearsal room, then go in the studio. I'm gonna go back to that. It's much simpler. It's easier. We're just saving up at the moment. I want to do it in Abbey Road. Eight days in Abbey Road, record the whole thing in a really tip top studio in a short period of time instead of spending up to two years. People come in, and then they go away, then they come back. It’s painful. I’ve heard that Brian Ferry does it like that as well. I think it’s closer to Brian Ferry than Eno actually. He’s like me, I'm like him, in that we're very fussy. People say you go in the studio with him and two years later, he's still doing that one track.

Did you have a concept for it?

It became almost conceptual when the pandemic hit, because I was walking around the perimeter of London. You get lots of ideas when you’re walking. So it was influenced by what's going on on the streets. Definitely. Like, Lookin’ Thru Glass, which is about a guy I saw sleeping outside Heals.

The furniture shop?

It’s for really rich people. Even I can’t get in Heals. The guy on the door said ‘You can’t come in’ when I walked in. I said, ‘I want to buy a light bulb.’ He went, ‘it’s not for you’. Anyway, there was a guy sleeping outside. I saw him over a period of a couple of weeks, in the doorway by the window. Then there was a bed in the window right behind him. So he was there and all he probably wanted was just behind the glass but he couldn't get to it. The verses are about that kind of thing, then the chorus is about a guy who's got everything and there's nothing left to buy. It's about those two extremes. There's a lot of shopping in there. I think I'm obsessed by consumerism. I love shopping but I hate it. It's one of them. I dislike buying tat and rubbish. You know when you go into Primark and you see the people just rummaging like it's a jumble sale. Throwing jeans and jumpers on the floor, because it's so cheap. They just think it doesn't matter. Put it on the floor. I hate that kind of consumerism. I love looking at things, saving up and buying something. You know, that kind of shopping I like. Because I live on my own, I'm always in supermarkets, observing how people act in supermarkets. The great big ones on the edge of town, the super, super stores. The 24 hour ones...I got to all of them while I was walking. There's a lot of consumerism in there on the album. Pandemic and consumerism, the poverty on the streets. It all kind of merges together. I think the easiest way is to listen to the songs and read all the sleeve notes rather than have me explaining. I'll get in a right tangle.

A lot of that you’ve been singing about since Denim, like Living On The Streets.

That's my bag, isn’t it? I can do that kind of song or I can do an abstract sort of song, like a Felt song, which I haven’t done for years. But there’s a couple on the album that could be Felt songs, lyrically, like And Now The Darkest Times Are Here. I left abstract alone for quite a while, but it's still there. I'm still capable of it.

Abstract was your thing for a long time in the ‘80s.

Stained Glass Windows In The Sky. If I could merge the two together, that'd be nice. Maybe I’ll do that in the future. But at the moment, yeah, it’s shopping, consumerism. It’s all informed by having no money and boredom. Everything I do is informed by that. Because, you know, when you’re not working with a band, you’ve got nothing to do. I'm not married, haven’t got kids. So I’m wandering around observing people. I’m an observer, wandering around trying not to waste the day. I don’t want to stay in bed all day. I want to get up and go out and do something every single day, even if it’s not music based. I might still be able to write some words when I’m walking around.

Really you want to be working with people though.

I love collaborating. I love it because you get a different perspective, they use different chords. I used to love writing with Maurice Deebank. I don’t want to just write on my own but I do like writing on my own as well. I like both.

How did it work with Deebank?

Mostly I would have like a little three chord song. And then he would do something over the top. He did about three songs where he came to me and said, ‘I’ve got this music’. One of them was Primitive Painters, where he did all the music. Usually I’d have a song and we’d sit in my bedroom like this. Then he does stuff over the top. With Terry, we write about six different ways. Usually starts with me giving him the lyrics, or sometimes we do it together in his room.

When was the last time you spoke to Deebank?

I spoke to Maurice in, I think, 1991, ‘92. He did a session with Saint Etienne, and so he was in London. They hired him for a track [Paper]. I went to the studio with them. They were doing it in a front room, actually, a studio in a front room. Kind of place I don't like. We spent an afternoon together and we got on fine, really well. That was when Denim was happening. I think the reviews of Denim had just come in and he saw one of them. I think it’s the NME review. He was really shocked, wow, this is really happening. Then he went away and that was it. We never kept in touch. He didn’t want to. I wanted to. I tried when we had these re-releases. I wrote him a letter. I wrote him two letters, in fact. I didn’t have his address, but I gave it to my publisher who has his address. So they sent it to him for me. And I tried really hard. I said, look, we won't be here much longer. Come on, we’ve got these re-releases coming out, let's sort things out, try to be friends. He didn’t reply. Nothing. Just no reply. He’s got some image of me that is totally wrong. I mean, have you seen that thing online that he’s done? It's very odd. He’s saying things...he’s written a thing, his version of what happened. It’s crazy. We all remember things differently. His version of Felt is so different to reality, though. It really is. It’s based on truth, but he says he taught us all to play, but, I mean, no. He didn’t teach us to play. We were not musicians. He was a musician. So we learnt from him, obviously, but it wasn’t like he sat us down and went, Okay, right, I’m going to teach you lot how to play bass and guitar. He took ownership of Felt when really it was a partnership. He took full ownership of it.

And Felt continued for five years after he left.

He said ‘when I left they carried on using my template’, which is not true. He was replaced by a keyboard for one thing. You know, it’s completely different. If we had solos in the songs it's because I love guitar solos. I always did. That’s why I got Maurice in the band in the first place. I wanted to do a band based on guitar solos.

You're Lawrence from Felt.

Yeah, it's crazy. [The full Maurice Deebank interview can be read here]. So he didn’t want to have a have a conversation or a relationship. I did try. Because I think out of all the people I worked with, Maurice and Martin Duffy are the ones I really treasure as something special happening between us. The rest of them, there are some good musicians here and there, some nice people, but they’re the special ones. Maurice and Martin and me, we’re the key to Felt.

And Martin’s gone now, so come on Maurice.

I mean, it wasn’t that I wanted to work with him again. I just wanted to have a chat. Just have a chat. But he didn't respond. He’s got a really funny image of me that’s just not true. Like I’m some master criminal. Some sort of deviant manipulator. That’s what he thinks. It’s simply because he couldn’t get his head around the fact that I want to be famous. He keeps going on about this fact, that when we started I was just obsessed with fame. So what? What, do you want to be a local band playing in pubs? What did he want? You need somebody with ambition to get out of your suburb. If everyone’s going ‘we shouldn't bother with fame’ then you’re not gonna get anywhere. He kept saying this thing about how I was obsessed with fame right from the beginning. Of course I was. I wanted the band to do well.

Have you any cause to listen to Felt recently?

Yeah, I did when we did the reissues some years ago, 2014 I think, which to me is just a couple of years ago. I had to immerse myself in it. Big time. I was all over it.

I've got this playlist, The Evolution of Lawrence. Starts with early Felt, goes through to the new record. It's an amazing body of work. I can’t think of such a high quality arc that's gone through so many dramatic changes and yet there’s something in it that is always constant. Obviously it’s you, the way you write and present your work. What would it take for you to get your dues, on a par with, say, Mark E.Smith?

I think it would take a cover version. Or if I worked with somebody else, like Charli XCX, someone who’s already famous. And they employed me and said, “give me some of your magic. Sprinkle some of your Lawrencian stardust on us”. I think then people might go, ‘Oh, God, yeah…Actually, yes, that Lawrence eh?’ One dip into the mainstream might do it.

Last time we spoke, you said Mark E.Smith was your only peer. Five days later he died.

I know.

He kept a certain level of fame and respect throughout, despite some bad records.

Towards the end they were terrible. I hate to say it because I loved him so much. I said to Adam at Cherry Red, the boss, let me produce him. Can't you ask Mark if I can produce The Fall? I'll go in with the band while he's not there and I'll listen to the song, then make them more poppy. Help them become more catchy. So that Mark is forced to make a melody. There was no kind of melody at the end, compared to Rebellious Jukebox or whatever. It's all melody in The Fall until Brix joined and then it's all riffs. Which is still okay. But then at the end there's nothing. I think I'm a different songwriter to him, but those early songs are remarkable. There's melody, twists and turns, amazing lyrics. They're very special.

So now he’s gone, you're on your own. Do you have any peers?

I think now it's Nick Cave. I'm obsessed by Nick Cave. The trajectory, looking at how he did it. I'd love to move into that world, where it's straddled the art world as well. If you can get into that then you’ve got the Sunday mag front cover scene. That would suit me. It's like rarefied air at the top that only some people breathe in. There's Nick Cave…can't think of many others where they're very popular and they do arenas, but they're also kind of underground. His songs are still really tough, a tough listen. I think Nick Cave is in the area that I'd like to get into. And when you hear about him, he lives this grand life. I mean, obviously, he's got massive personal problems, events that've happened to him, but in the music world he's in the rarefied air. And there are not many people up there.

One thing you have that sets you apart is the attention to every minute detail of what you do, how you present your work. Like those inserts in the new record.

Yeah, that's true.

The Thoughts and Opinions of Lawrence and Various Other Sardonic Lucifers. Let me ask you about some of these thoughts.

OK.

The artist is a rebel who defies control through his work. How would that manifest?

Otherwise your life is haphazard and there is no focus. The work keeps you alive.

Next: I use counterfeit admiration.

Because it’s much easier. Like in everyday life when I'm at the cafe or something, and instead of being negative about anything, which I’ve noticed most people I know are - Oh, that's crap, this is crap, I hate them - for me, it's just much easier to just say it's really good. If someone says I'm going to see this new sci-fi film, and I can't stand that kind of stuff, instead of saying ‘what are you gonna see that crap for?’, instead of getting into all that I just go, Wow, that's good. That's counterfeit admiration.

Beautiful people have a special power and their charisma is a form of intelligence.

I love beauty. I've been attracted to it all my life. They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but it’s not really. There are beautiful people. Yes, we like quirky people. I like girls with big ears, for example. That’s my quirk. But there are beautiful people. You have to admit it, there are, and it opens a door for them which isn’t open for the rest of us. Kate Moss, for example. They just seem above us, above the normal people. Like gods. It’s something you’re born with. So lucky.

What have you been reading recently?

Okay, so the last book I've read is No Place Like Home: Britain's Housing Tragedy, by Frank Allaun. I love the story of housing. We all romanticise slums. But really they're not fit for human habitation. We had to have something new, but unfortunately it was these horrible tower blocks that were worse than the slums because they fell to pieces, leaking, cockroaches, lifts don't work. So I'm interested in that subject, from the Victorian age to now.

What have you been watching?

I haven’t got Netflix or anything. Nightmare. And YouTube takes about ten minutes to get going. I don't know why, but I can't get it. I've got this channel, PSB. It's really good. It’s Public Service Broadcasting, from America. I watched the Vietnam documentary. Wow. It’s by Ken Burns. Bloody hell, what a stunner. That's what I watched over Christmas, the best thing I've seen for ages. I'm still watching the soaps.

Last time we spoke you were hoping to get a role on Emmerdale.

As soon as I said that it went downhill. Typical. I really liked a woman on it...

Chastity Dingle.

Chastity Dingle. After I said that, her character took such a swerve. It was awful. They cut this whole backstory on why she was like she was, which we never knew before. It’s best that we didn't know because it was a ridiculous story, about the abuse that she took as a child. We didn’t need to know. They ruined the character. She became a real victim instead of what she was before, a brassy broad in typical soap style, like Elsie Tanner. So I went off that but I'm still watching soaps. They just drive me mad. Is Danny Dyer dead?

Is Danny Dyer dead?

He went in the water at Christmas to save his wife. She’d already crawled out.

This is EastEnders, isn’t it? I haven't watched it for over twenty years. I couldn’t cope with the idea that they were stuck in Walford.

You need a passport to get out of Walford. They’ve started saying Shoreditch now. They used to go, ‘we're going up west’ that was a big deal. Get your passport ready. But now it’s ‘there's a new night on in Shoreditch!’ So funny. And Phil Mitchell, this is the best, he came home to Sharon one evening. ‘I've been down that butchers you love in Bethnal Green.’ I know that butchers! “Got you them steaks.” I know where he means! That’s the butchers on the Relative Poverty sleeve! When they pull the shutters down it says ‘BEEF’.

Why did you re-record Relative Poverty? I liked the original.

I mean, it's okay. But what happened was we started playing it live and the response to it was, Oh my God, people love this song. We were in the rehearsal room, we did a really good version of it, so we just said we should re-record this. It’s still relevant. It became more relevant the more time went on.

A song about surviving on a tenner a day is very relevant.

We do a really good version of it. It was just a bit lost on that record. I’m really happy with it. I love the video Douglas Hart did of it too.

I really love the two videos we've done because they're not like normal videos. We've done three videos now...

What's the third?

When You're Depressed. We've done Depressed, Poverty, Record Store Day. Yes. So we did three proper videos. And we're redoing Primitive Painters.

What?!

Yes. Not the song. Cherry Red are forty-five years old and they're doing 45 on 45. So some of the singles, like Everything But The Girl, Dead Kennedys, they’re releasing on 10 inch, and one of them is Primitive Painters. I said well, look, we can finally get this video finished. Because what you see online is half a video. We never finished it. There was a big argument, Creation and Cherry Red had a big fall out, nobody paid to finish it, there was a whole hoo-ha about it. And then somebody just put it online.

It was a rough cut just to show somebody. We're using that footage and we shot more footage. Hopefully that should be out this year. And we’re online as well. There's a site and everything. I don't do it. This guy runs it for me. Yeah, for nothing. Just because he likes us. Usually, I mean, that would cost ten grand a year or something. Costs a lot. It’s called Lawrence Land. That's just for buying. If you want to buy a t-shirt or record or anything you go to Lawrence Land. I said if we go on the Internet I want it all to be about buying. I don't want it to be about like, 'Oh, hi everybody. I'm just going to the cafe. See you tomorrow morning'. You know that shit that people do? Can't bear it. For me, it's about selling the product. Did you see the book sale thing we did? I sold my books.

I did see that.

I had two booksellers round and they wouldn't buy them. I just wanted to get rid of loads of books, but I didn't want to give them to charity because they were really expensive. I thought let's have a book sale. We had it at this shop in Broadway Market. We had loads of fans. I was there taking the cash for the books, talking to all the fans. It was amazing. I sold loads of really expensive ones. That guy from Spiritualized spent the most.

Jason Pierce?

Yeah, amazing. He came in, had a look around and then went out. I thought, God. Then he came back! He must have gone to get some money. He spent the most, over £200. He bought a William Burroughs book, because I don't need the hardback.

Do you listen to any new music?

My friends say I'd love The 1975. So I bought that album. I haven't played it yet. I just use Fopp as a library.

Really?

Yeah, because I want to hear new stuff. I’m not going to keep it. I buy it on CD and sell it if I don’t like it.

That's what streaming is all for.

It’s my form of streaming. It’s a really expensive kind of streaming. I put them in a bag and I'll sell them eventually, you know, to a record store. But something like The 1975 or the new Paul Weller, I want to hear them.

You should just get get Spotify.

No, I don’t want to do it. It's bad for me. I could get YouTube going, which takes ten minutes, and then watch the video. Then I could do get an idea first. I should do that. And then I could look at The 1975 and think, Oh, I do like them or no, I don’t like them, instead of paying £7.99. I want to hear new stuff. I really want to like something new. But it's hard, isn’t it? I like Charli XCX. It's kind of dead now because I keep talking about it all the time. Once you've done it two or three times in interviews people are bored by it. I went to see her at Ally Pally.

How was it?

It was amazing. Ten thousand people! I thought where's the band? There must be a band, like a real old man. There must be a band hidden somewhere. No band. She’s practically miming to the CD. Incredible. She was dancing for two hours. I was watching on a big screen to see if she went wrong or stopped. Not at all. Choreography was incredible. It was just her and two men, dancing and singing. People went mad. She’s really, really amazing. And she worked with Ariel Pink. So she worked with him, come on. If I keep talking about her, she might go, “Oh, he's interesting.”

TK