Hello!

Monday, Monday, doesn’t get any better the more you say it does it? Gets worse actually. But then there’s a point around the tenth Monday where you realise you sound like a Brummie saying Mandy and then it starts to get quite enjoyable. See, always looking for positives.

Today we’ve got an in-depth chat with production dynamo James Ford that takes in his solo record, Arctic Monkeys, Klaxons, Test Icicles, Depeche Mode, Brian Eno and more until we get interrupted by the Pet Shop Boys, which we’re totally fine with, they’ve earned it really.

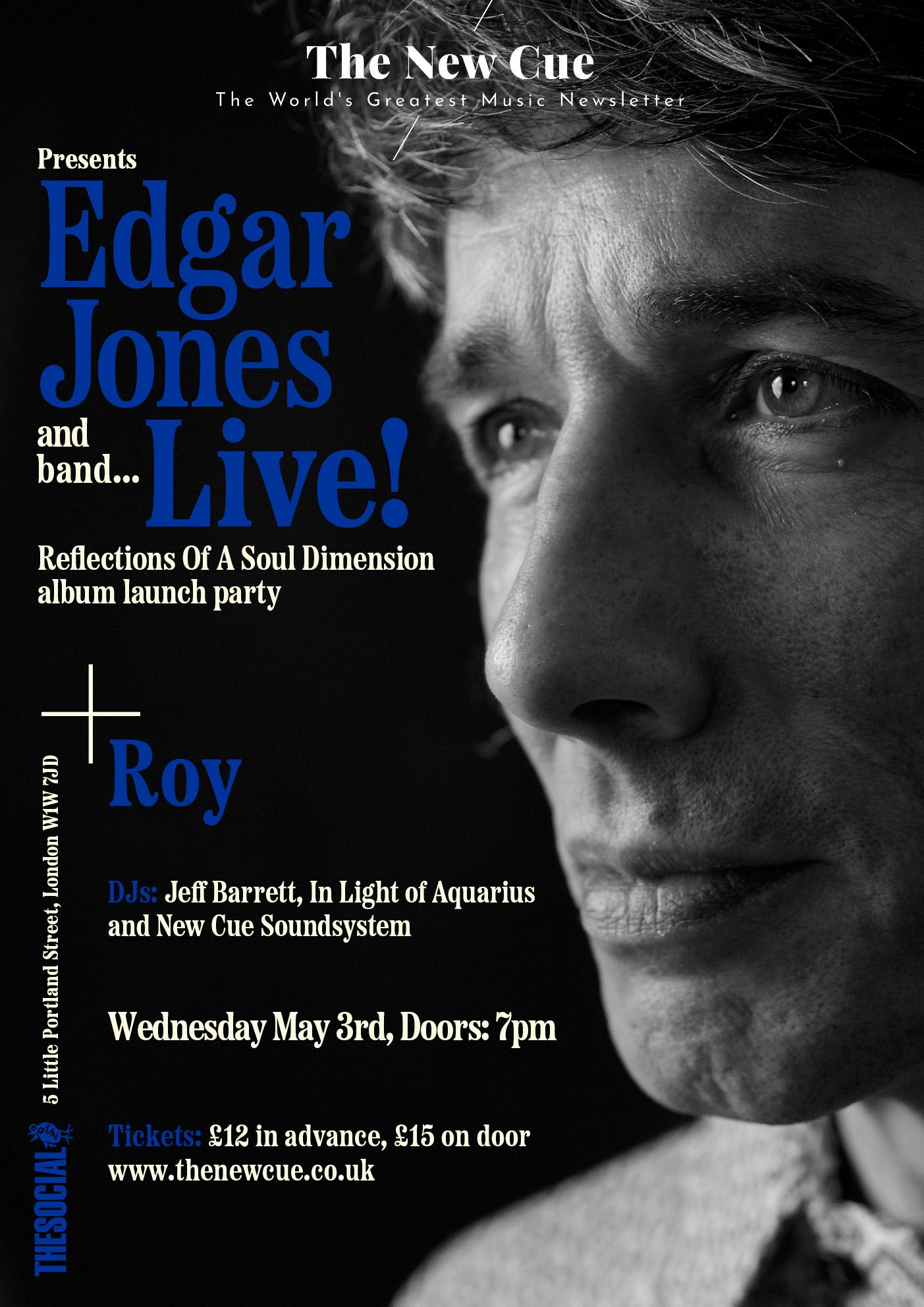

Oh, before we forget. Have you got your ticket for the Edgar Jones gig at The Social on May 3rd, with Roy supporting?

Half the tickets are gone now, but we want it packed for the launch of the album of the year. So come and bear witness to the mightiest of Scouse Soul Power!

Meanwhile, please enjoy the edition,

Ted, Niall and Chris

Start The Week With… James Ford

James Ford is one of the most influential figures in modern music. Born and raised in Leek, Staffordshire, he first came to prominence as the drummer in indie-pop experimentalists Simian. They split up in 2005, though, and Ford and fellow member Jas Shaw formed a spin-off electronic duo called Simian Mobile Disco. A year later, Justice remixed the Simian song Never Be Alone into We Are Your Friends. Might as well stick it below, it’s an absolute banger:

That will be the only non-James Ford production we’ll have in today’s letter because by then he was already making waves as a hotshot producer. His highlights are almost too many to mention. Since helping to create the defining record of nu-rave with Klaxons’ Mercury-winning debut Myths Of The Near Future, Ford has co-produced the first three Florence And The Machine albums, manned the mixing desk on Foals’ brilliant What Went Down, worked with Haim, Gorillaz and Jessie Ware whilst also becoming an artistic foil for Depeche Mode on 2017’s Spirit and the newly-released Memento Mori. The thread that runs the whole way through his production career, though, is his work with Arctic Monkeys, his relationship with them going back to 2007’s Favourite Worst Nightmare.

Somewhere amongst all this, James has also found the time to make his solo debut, being released under his full name of James Ellis Ford. Titled The Hum, it’s out in May and it’s a mesmerizing blend of hooky psych-pop and ambient soundscapes. Here’s the brilliant first single from it:

A couple of weeks ago, Niall hopped on Zoom to speak to James about its creation, hear about the inner-workings of Arctic Monkeys and most importantly to find out if he still lived in Niall’s uncle’s old house. It’s also definitely the first New Cue interview to end prematurely because the Pet Shop Boys have arrived. Here’s a playlist of Ford’s finest cuts to listen along whilst you read:

Hello James, where are you?

I’m in my studio, which is in an attic room in my house.

How’s your Wednesday morning been?

Busy, hectic. I’m in the middle of a bunch of different projects at the minute. I’m making a Pet Shop Boys record. And my kid’s off school because of the strike, he’s downstairs drawing a pirate ship. I’m busy but good.

How much of being a producer operating at the top level involves not being able to talk about half the things you’re doing?

Yeah, that’s partly why I stay off social media. I’ve been burned in the past where I’ll do a photo or say something on and then people are like, ‘oh, we weren’t going to announce that yet!’ or it just blows someone’s campaign. I’m a fairly reserved guy, I’d rather be in the background anyway. I tend to keep my head down and keep quiet and get on with it.

Are you still in the same house you got from my Uncle Chas?

Hahaha, from your Uncle? Yeah! I remember they were really lovely. Yeah, it’s the same house. We extended it, I’m in the loft of it now. We love it here. It’s different than it was, a lot of the old, cool guys probably like your uncle are moving out because of twats like me. It was good up to a point and obviously you can get a nice coffee and stuff nowadays but our cool neighbours all got priced out and now it’s all city boys and lawyers and hedge-fund managers. It’s a long running joke with the people at the coffee shop because I walk in there now and again with Perry Farrell or something and people are like, ‘what is happening?!’ because it’s still a local area.

How important is it to you that you’ve got a home base to work from rather than operating from some top-end studio?

I’m toying with the idea of getting a bigger place but then most of the projects I do, like for the Depeche Mode album I was in America, Arctic Monkeys was out in France or in the countryside somewhere, a lot of the time the bands that I work with will want to go somewhere to record and then I come back here and I can finish so much stuff here. I mixed the Monkeys in here, I did all of the Jessie Ware record in here, including drums and stuff apart from the strings. You can do a lot, it’s just quite cramped, but it’s working pretty well for me. I would love to have like somewhere like The Church, one of those nice big studios. I’ve always had that like romantic idea of being like a [legendary jazz studio owner and engineer] Rudy Van Gelder where you really get to know all the corners of the room and what mics work in what spots, where the drums sound great, obviously you can’t really do that in here.

But everything is so wired in here that it’s really quick if I want to get an idea together, I know exactly what bit of gear will get there, it’s two patches on the patch bay and it’s up and running, there’s no searching around for an adapter or trying to find the cable to plug it in because sometimes that sort of thing just kills the idea before it starts. The convenience is a big factor. I’ve definitely found with my own record, less so with other people’s, but I’m quite lazy in that respect, I just want to get something done quickly to see if it’s even going to go anywhere.

Your solo record is great. Did you do it all there?

Yeah, it was all here. I’ve only really had this studio for four or five years and it’s definitely enabled much more time for me to just fuck around, I’ve got some tape machines over there, like a Frippatronics kind of drone-y area that I’ll play with on an evening instead of watching a crime drama on the telly or something. If I’ve got a spare hour or something, I can just nip up and fuck around for a bit. Jas from Simian Mobile Disco got sick and through the pandemic, it meant I wasn’t able to be in a room with him because he was isolating plus the dead time that we all got over the pandemic meant I had a bit of time to focus on doing my own stuff, which has been bubbling over for ages.

I was expecting it to be ambient heavy but there’s some really straightforward songs on there too.

Yeah, honestly, I could have made a whole record of ambient-y stuff, that probably was where I started and that’s what I listen to quite a lot, Harold Budd and all that sort of stuff. But then I started exploring and playing around with more chord-y stuff and melody ideas. At the beginning, I didn’t really think I was making a record, I was just like, ‘I’ve just got some energy to pursue some stuff on my own for a change and see where that goes’. I actually did have the intention to maybe get some singers so I started to write some melodies and rough lyrics and then started to think it was probably a bit bolder to do it myself. I was in a position where I wanted to challenge myself and push myself out of my comfort zone. The biggest thing for me in that respect is using my voice, because I find that makes me feel quite vulnerable. What I grew up with has always been that Canterbury proggy sort of stuff. I inherited my dad’s record collection and we still talk a lot about music. I grew up with bands like Caravan and Gentle Giant and Robert Wyatt and all of those things. Without knowing it, it’s my default setting.

Were there any trusted confidants you were bouncing it off?

Not for a while. The first people I played it to was my dad, and Jas and a couple of friends, then maybe management. And then a few of the songs getting decent reactions gave me a bit of confidence to carry on. It’s funny, it made me feel like a teenager doing the whole thing.

What tweaks do you have to make in how you work when you’re producing yourself?

One thing I was aware of, which I’m aware of with other people, is to try not to fuck around with it too much because the technology is there to fix any mistakes. I try not to do that with other people’s records, not putting things in time and in tune too much because I think that human-ness and that wonkiness is what I love to hear in other people’s records and often gets ironed out in a modern production process. To not do that to yourself is harder - it’s easy to hear someone else’s mistakes and see the value in it, but it’s hard to see the value in your own mistakes a lot of the time. I was quite dogmatically first take of everything so it’s almost like everything is improvised in a way.

How naturally did it come writing lyrics?

I’m definitely noticed working with a lot of great lyricists - I notice people like Alex Turner will be constantly thinking about lyrics and taking snippets from people’s conversations and jotting stuff down in his notepad. I definitely don’t think in those terms, a lot of the time I’m very much into melody and chords and feel, but I felt like I opened a little extra door in my brain when I suddenly started thinking about lyrics, seeing little things and thinking, ‘Oh, I’m gonna have that.’

What was your first job in music?

I went to Manchester to do a biology degree. I’d been playing in bands when I was younger, in my little town of Leek, and when I got to Manchester, somehow I started playing drums in a club. A guy called Graham Massey [of 808 State] saw the club I was playing in and I got on with him and then my first actual job where I got paid for drumming was playing for 808 State. We toured, it was the first time I ever went to America, we did all these weird like candy raver, pre-EDM shows, almost more like a Grateful Dead gig but everyone was ravers. I was 18, 19, 20 and that was my first professional gig. Then we started the band Simian at college and made an album in our basement. We got signed a year after college ended and moved to London, so that was probably when I became professional.

What was the point at which you stopped thinking of yourself as a drummer and started thinking of yourself as a producer?

I always thought I was a bass player! I’d played bass in bands and I still like playing bass. I took up drums because I answered a noticeboard asking for a drummer, it was a bass player and a guitarist. If it was asking for a bass player I would have done that. So I went in to be a drummer and it was actually Jas and Alex, it became the early days of Simian. But we got to the second Simian record and we all fell out, we had this mad time and loads of major label pressure, classic second album struggles. We split up and we had a studio in The Premises on Hackney Road. Everyone went off to get jobs and I was like, ‘fuck it, I’m not ready to get a proper job yet, I’m gonna take over the rent on the studio and try and be a producer.’

It had been bubbling in my head for ages, even since I was 14 or 15. I remember having a four-track in my dad’s basement, a drum kit and a little synth trying to recreate Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters, but as a 15-year-old without the chops of Herbie Hancock or his band. But I remember that feeling of ‘this is the fucking best thing ever!’, just recording stuff and faders and putting mics around, so I had it in my head for a while but it maybe crystallised when the band split up. It was gutting, it was like the end of the world - ‘What am I going to fucking do now?’. Then luckily, one thing led to another and I did a DJ gig and found my manager who had some good connections into local bands. I managed to do some friends’ bands and a few little known bands, just with the same set-up that we had with Simian. One of them was Test Icicles, that was on Domino and then Lawrence [Bell, Domino honcho] put us on to meet Arctic Monkeys. You get this little snowball effect that starts to happen when you get a few things going, then once you get a few of the bigger records through that was it.

Which production gig has been the biggest learning curve for you?

It sounds trite, but they all are, it’s never like you walk in and it’s gonna be a breeze. It’s a constantly shifting arena and there’s lots of different ways you can approach it. Those early days, I remember taking my home PC down to Eel Pie Island and recording the first Mystery Jets record, that was pretty wild to be out in the field, literally in a boat shed with a bunch of mad kids trying to make a record. Then there’s those early times in the studio, picking up proper studio techniques. Even now, going in with some of the older bands like Depeche Mode, there’s a whole different set of approaches and strategies about managing people, all of those things.

I remember on the second Simian record, Brian Eno came in. He was interested in us and came into the studio for a few weeks while we were doing that record. I remember observing him doing his thing, and how his calm presence changed the whole vibe, because we were pretty dysfunctional at that point in terms of our relationship. At the time, I remember thinking ‘he didn’t barely do fuck all, he was just making tea!’ but then it dawned on me not long after that that I see what he was doing. I was thinking, ‘I could probably do that’.

There’s so many little learning curves, like doing the failed second Klaxons album where we all took a load of fucking weird drugs and it went super psychedelic. The label came out, they’d buried stuff out in the field and there’s all those crazy stories about talking to aliens and all that stuff. There’s so many weird different experiences that make you into a producer and I think being a producer is something that it’s experience that is one of the main strings to your bow, being able to navigate different situations, trying to get the best out of whatever that situation presents you with.

The defining relationship in your production career is your work with Arctic Monkeys, which goes all the way back to their second record Favourite Worst Nightmare. Can you give me an insight into how a modern Arctic Monkeys record is made, I think a lot of people find their dynamic quite intriguing.

Yeah, that’s the thing, even within one band, it changes every record. With the most recent record, Alex is getting very into recording stuff himself. He’s a polymath at the best of times, he plays everything, he’s into the sonics of it and he’s obviously writing the songs for the most part. He does pretty great demos on this thing called a Tascam 38-8, it’s like an eight-track tape machine and it’s got a real vibey sound. He’ll come in with pretty well-formed ideas at this point, it definitely used to be less formed when they came in, although they’ve always been pretty well organised.

I seem to remember the writing process for The Car was quite long, he went to and fro with a few different direct directions. He definitely did a fair amount of writing, he had his own studio in London somewhere and Jamie [Cook, guitarist] and the band were coming in and out, jamming, then he’d do four or five different versions of the same song with different tempos and he’d played some of them to me and I’d be like, ‘Oh, that one’s sounding great.’ Then eventually, he came in and did some stuff in here, where we’d get his demos up, and maybe do some structural stuff and think about how we would actually record it. The last record was in a pandemic still so we couldn’t go abroad to a studio that we’ve been to quite a lot. We went to this country house in Suffolk, which involved pulling my studio apart and renting loads of stuff. It was quite a big technical thing. I just remember doing loads of wiring, plugging in the studio, getting it to work. The recording set-up was quite slapdash in a lot of ways but it ended up being a really lovely experience out there and we got it sounding really good after a bit of luck and a bit of hard work. After that, we brought it back here and me and Al did the string arrangements, pushing notes around on the screen. Then we went and got the string stuff done with this girl called Bridget Samuels who’s brilliant, she translated it into all the dots and that. Then I mixed it in this room.

It sounds like quite an insular process.

Yeah, it’s funny, I’ve known them so long now. I’ve been working with quite a lot of new bands and you get this energy and respect or something that you have in a new relationship and it counts for quite a lot. People will try stuff out that they wouldn’t normally try. But with the Monkeys, it’s a totally different thing where there’s this deep trust that we’ve grown up together.

So there’s a shorthand?

Yeah, that’s the thing. Me and Alex, our music tastes have grown together, I’ve introduced him and he’s introduced me to so much different music and there’s so much that you don’t even have to bother explaining. But sometimes that’s good and bad. I do often think it would be interesting to see what they did with someone else at this point, not that I’d really want them to, but I think that maybe they should, or it might be like a marriage where it just wouldn’t work. It’s a funny thing, but I still definitely try and push him as hard as I can. I’m aware I don’t want him to settle into a comfort zone and it just become boring, you’re trying to keep finding ways to move forward and do new things.

Which record that you’ve been involved with across your career that you think is underrated?

Maybe just because we’ve been talking about Alex, but I remember really liking this one called Belladonna Of Sadness by Alexandra Savior that me and Al did. I remember really enjoying making that and thinking it sounded great, but no-one ever really heard it. There’s lots of ones that you think are gonna do great but don’t, then ones that you’re not so keen on that suddenly have this life of their own.

[at this point, James’ little lad walks on screen and whispers into his ear]

Oh, my little boy has just told me that the band are here. Sorry, I’ve got to go, the Pet Shop Boys are here! Have you got enough?

That’ll do just fine, great way to end an interview! Thanks for your time, James.

Thanks very much, man, nice to speak to you.

ND