The New Cue #284 May 15: Paul Simonon

"We were always more concerned with protecting The Clash’s legacy rather than squandering it."

Hi, hello, good morning,

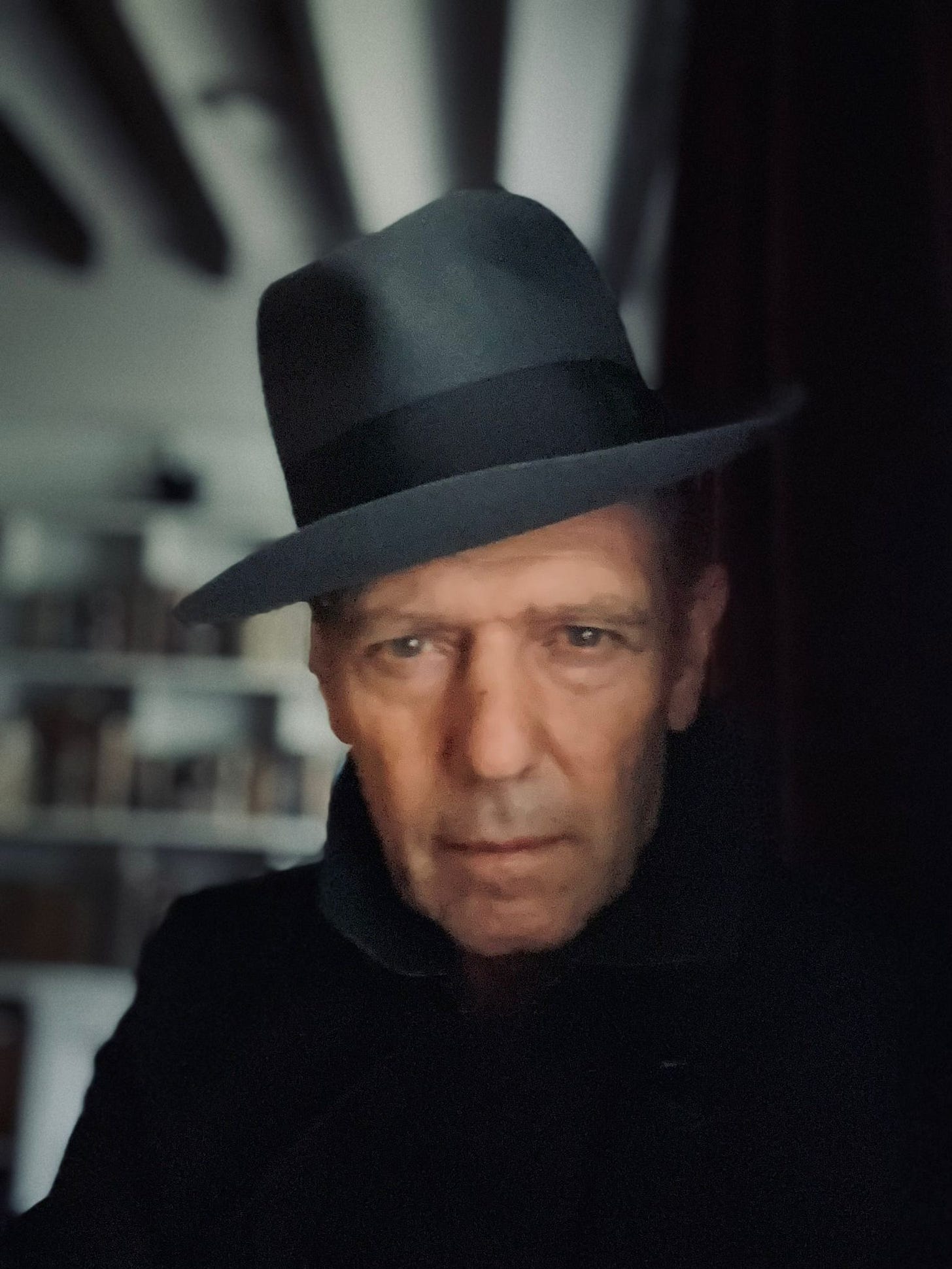

Today, we have none other than The Clash’s bass-smashing style icon Paul Simonon in the hotseat. As well as being the best-dressed and most handsome man in rock and roll, Paul has a new album out on Friday called Can We Do Tomorrow Another Day, which he recorded with singer-songwriter Galen Ayers, daughter of The Soft Machine’s late psychedelic minstrel Kevin Ayers. Once you get to the end of our chat with Paul, Galen has picked some mind-blowing musical gear for you too.

Enjoy the edition,

Ted, Niall and Chris

Start The Week With… Paul Simonon

Some people just look like rock stars. Witness for the prosecution: Paul Simonon. As a 21-year-old, Brixton-raised Simonon was invited to join the band guitarist Mick Jones was forming despite the fact he had never picked up a bass guitar in his life. That didn’t stop him becoming an integral part of The Clash, Simonon’s reggae-informed bass lines and his visual input as important an ingredient towards The Clash’s iconography as the songwriting partnership between Jones and frontman Joe Strummer. After The Clash spluttered to a halt after 1985’s disappointing Mick Jones-less Cut The Crap, Paul very briefly played with Bob Dylan, then he formed Havana 3am with singer Nigel Dixon. The group released one self-titled album in 1991, but Dixon sadly passed away two years later.

For much of the 90s Simonon returned to his first love, painting, before being tempted out of musical retirement by Damon Albarn. He formed The Good The Bad And The Queen with Albarn, The Verve’s Simon Tong and legendary Afrobeat drummer Tony Allen.

Albarn also managed a Clash reunion of sorts by roping in Paul and Mick Jones to be part of Gorillaz’s touring band.

On Friday, Paul releases the first album from his new project Galen & Paul, a collaboration with singer-songwriter Galen Ayers, who has some solid musical heritage of her own as the daughter of The Soft Machine’s Kevin Ayers. Here’s a little taster of the album…

Chris spoke to Paul over Zoom a couple of weeks ago about the record, The Clash, TGTB&TQ and a whole lot more. Galen has also very kindly picked an album to blow your mind which is at the end of the chat with Paul...

Hi, Paul. How are you doing?

Yeah, I’m good thanks.

Are you at home or are you in the studio?

I’m in my studio and my home. The studio could feasibly be in the kitchen or anywhere.

What do you miss when you’re not at home in London?

How grumpy people are with each other on the street. You go to Spain, and everyone’s so polite and civilised. It’s disarming. You come here and everyone’s got a problem with each other. That’s what I’m used to and in a strange way, I miss it.

Your new album has a real mix of European styles on it...

Most definitely. When I was a kid my granddad used to play Jacques Brel and my dad liked Françoise Hardy. But then growing up in South London and Ladbroke Grove I got exposed to West Indian music; ska, rocksteady, reggae. So I’ve always listened to all kinds of music. And then there was a period where I lived in Italy with my stepfather and my mum and I was exposed to lots of Italian music and spaghetti westerns.

Has music always been tied into the visual side of things for you?

It’s feelings. A song evokes many things. It can cheer people up, it can piss people off. For every emotion possible, there’s a record for it. Hopefully our record has got quite a range on it. Essentially, it’s a European record. We’re not part of Europe anymore, but it’s as if we were. My mum was born in Nice, one granddad was from Whitby, my dad was born in Camberwell and his father was from Belgium. So I’m a bit of everywhere.

Was moving from Brixton to Italy when you were a kid a culture shock?

Totally. My father left, which was a shock to me, and my stepfather turned up and he won some scholarship to study music in Italy. So suddenly we left Brixton and went to Italy. All of a sudden it was like: Olives! Pasta! Pizza! We didn’t have Pizza Hut or any of those things in this country. And I was allowed to drink wine and get sloshed. My mother thought that the Italian boys drank wine but she didn’t realise that it was actually watered-down so I got quite sloshed playing with my Action Man. We were only there for eight months, but it was quite an experience.

That must have been amazing coming back to London and having this melting pop of culture spinning around in your head…

Well, even more so coming back and living in Brixton at the time. All my mates at primary school had originated from the West Indies, so I was exposed to music that when I came back had slightly altered from ska into rocksteady.

Were you a bit of a skinhead back then?

Oh yeah, totally. When you say skinhead now people flinch, but back in the day it was an offshoot of the mod movement and a lot of the reggae artist that came over used to have skinheads as their security. It was definitely very pro-black in those days, but then an element of it changed.

With mods and the early skinheads it was very much about style and clothes and attention to detail. When punk came along, did you see it as a continuation of that?

In a slightly different way. Everyone had different sensibilities. The skinhead thing was a reaction to the hippie movement, and the mods a reaction to the rockers and I think with the punk, it was that everyone had their own individual experience. Mine was the sort of mod, skinhead thing. The thing that made it a lot easier for us was that we used to get all our stuff from secondhand stores. At a period when everybody was wearing flares, straight leg trousers were dead easy to get and very cheap. The Clash couldn’t really go to Vivienne [Westwood]’s shop where The Sex Pistols got their stuff from because then we’d look like them. It was very much do-it-yourself. That was my background, I was always wearing secondhand clothes.

Do you think looking back at it, that looking good and being stylish was what landed you the gig in what would become The Clash in the first place? When Mick and Bernie [Rhodes, The Clash’s manager] asked you, you didn’t even play an instrument.

Maybe. Bernie’s attitude was to mix musicians with non-musicians. Bernie was responsible for getting John Lydon to be the singer in the Pistols, I guess so, I dunno. You’d have to ask Bernie, maybe there was another reason.

When did the idea for this new album come into your head?

Living in Majorca, I was working on some paintings out there in this sort of semi-deserted fishing village. I was there in the winter period for a couple of months working. I had a guitar and I just for the hell of it decided to start playing and writing songs then with some of the local guys I started busking in the street. I came back to London and ran into Galen, who I’ve known for quite a while, and we were both in the same sort of spot, emotionally and mentally, and it just came together. She had a bunch of songs and I had a bunch of songs, we worked closely and came up with a bunch of new ones. I never thought about singing, I’d wanted to have someone else singing on it but she was like there’s no way I’m singing all these songs on my own, we have to sing them together. So that’s when it started to have this interesting blend.

Did you want it to sound a bit like Jacques Brel or a bit like Françoise Hardy or Django Reinhardt?

Yes, and no. Maybe it came out more in terms of ideas coming across the table. There’s a sort of messed up memory bank in my head, so I don’t know directly where the source is from, but I know it’s from somewhere. It’s all jumbled up references from somewhere. To be honest, a lot of the songs called out themselves how they wanted to be, you just find the foundation or the basic structure and you think, ‘Oh that needs a trumpet!’

Some of it sounds a bit pre-rock and roll.

That’s probably a connection more to do with my background in Brixton and Ladbroke Grove. I recall making a comment about the album that I made with Damon, [second TGTB&TQ album] Merrie Land, that it was sort of like if reggae was there, but rock and roll hadn’t been invented. I suppose an element of that is how I play and how I approach things musically. I learnt playing along to reggae records. Because I could hear the bass for a start. It was a good way to learn. Mick Jones showed me the rudiments and the basic things. It wasn’t until our third album that I came up with some bass ideas because in the early days I was still trying to learn how to play.

The third Clash album, London Calling, had the first song you ever wrote on it, The Guns Of Brixton. As far as first efforts go, that’s not bad!

I always had lots of things brewing, but I was distracted by working with Bernie on the artwork and clothes or chucking paint over clothes. From day one, we were pretty much non-stop touring. We didn’t have a holiday for as long as it lasted. It was seven years non-stop. Things were brewing that never came out and then it went into that song. There you go, let’s try that again.

Having two prolific songwriters in the band, it must have been hard to chip in yourself?

Yeah. That’s the thing, with Strummer/Jones how do you compete with that? It’s not competing, it’s just trying to have your own voice.

Were Joe and Mick encouraging about your songwriting?

Always. Absolutely. Mick and Joe were always really encouraging. In fact, I initially gave the lyrics for Guns Of Brixton to Joe to sing. He just said: No, you’ve got to sing it, they’re your lyrics. Ahhh, OK.

You mentioned Damon earlier. Is he on the new record?

He is. He was hired in to play melodica. He said that nobody had ever asked him to play melodica on their records because usually, if he’s involved, he’s usually the one making the record. So it was nice. He’d just got off the plane from Australia and he was jet-lagged and it was great to have him on the record. He’s just my mate.

It’s been 15 years since the first The Good, The Bad And The Queen record so he’s also one of your longest-running collaborators.

Yeah. We hit it off pretty much straightaway. We both discovered that we had a real love of our area where we lived, the streets and the history. And also we both were really into old school music hall, [30s/40s double act] Flanagan and Alan and all that stuff. All those cockney songs about the houses in between.

That’s fascinating, The Good The Bad And The Queen came out of your shared love of London history.

Absolutely. Like a [London historian] Peter Ackroyd biography in music.

Do you see much of Mick Jones these days?

I see him about once a year. I see Topper as well. It depends if someone is working on different projects or is out of the country but we’re all still in contact.

I remember hearing that someone had asked you for Mick Jones’ phone number and you said you had as much chance just calling a number from the phone book at random and asking to speak to Mick Jones as you did Mick answering his phone.

Ha! Yeah. That’s like ringing his doorbell as well.

Do you have any regrets that you never played together before Joe passed away?

Not really. Personally, I felt we’d sort of done our job in a way. I guess if we had made a new record, maybe, but then I suppose everyone would have gone into different directions… B.A.D. were so groundbreaking I didn’t feel there was any need for Mick to do it and I don’t think Joe would have been happy retreading steps that he’d made already. I didn’t really see much point. Obviously, it meant a lot to so many people and it meant a lot to us, but I think we were always more concerned with protecting The Clash’s legacy rather than squandering it. Move on, make something new. It’s healthy to do that. That’s why doing this project with Galen is so great. It’s new territory. It’s jumping in the deep end, hopefully I can float. It’s like with anything do if you’re creative, whether it’s painting or music or writing a poem, you need to be inspired about the project.

Before The Good The Bad And The Queen had you lost interest in music?

Well, my friend who I’d been in [Simonon’s early ‘90s post-Clash bad with singer Nigel Dixon] Havana 3AM with, he died. He had malignant melanoma which is like skin cancer and he died. Shortly after that my two sons were born and I wanted to take a step back and just focus on painting and to be involved with my kids growing up. I was really fortunate to be able to be there and not have to get a nine-to-five job.

You were fortunate to have painting as another creative outlet.

Yeah, I was always fortunate with that. I suppose for Mick and Joe they only had music whereas for me I had painting. It was painting first before I got into music. There’s a challenge for me to try and find a balance between the two, but I think I’ve found that now where I can do a bit of painting then do a bit of music.

And it was Damon who tempted you out of musical retirement?

It was. We’d sort of met a few times before and we talked about doing some music. He had a few ideas that he rescued from this project he was doing in Nigeria and wanted me to put some basslines to it. And at this point, we started talking about our neighbourhood and London, and suddenly it took on a whole new direction.

What was it like being in a rhythm section with Tony Allen?

Initially, very complicated. But then I realised that my nature of playing is like footsteps or dance steps, it’s very steady, so that allowed Tony to go off grow all that colour and sound. In some ways I was acting like the bass drum. He did say to me: ‘Whatever you do, don’t follow me.’ I was like, ‘What do you mean?’ Normally the bass and drums are supposed to be linked. What he meant was if he went off and did a fancy fill a bassist would try and follow him and emulate it. That was fine with me, I didn’t want to do that anyway, so it all worked out really well. It came from Damon thinking, ‘I wonder what it would be like if Tony and Paul got together…’ And it turned out really well. I was really lucky to spend time with Tony in the back of the tour bus, drinking whisky and playing songs.

Do you ever stop and think about the journey music has taken you on?

I don’t really have time to stand still to think about things like that. But now you mention it… I grew up playing on bomb sites as kid and that was an amazing experience, and hanging out of kids from the West Indies - that was an amazing experience. But then when you’re that age, you think the whole world is like that. It’s only when you get older you realise that, actually, in Knightsbridge they don’t have any bomb sites. Well, I never saw one in Knightsbridge.

Will there be another Galen and Paul album after this one?

Let’s see how it goes. I can never predict tomorrow, but I’m looking forward to tomorrow. Looking back to yesterday, I’m not really good at that. I think it’s probably because I went to so many schools as a kid and made friends and then suddenly after a month or whatever I’d have to leave and go to another school and be the new boy because my dad was looking for work. So I’m quite good at moving on and not bringing any baggage with me. Maybe that’s one of the things that might answer the Mick Jones/Bernie Rhodes question. They probably thought I was interesting because I didn’t have any baggage.

Thanks so much for talking to us Paul.

That’s alright mister, cheerio!

CC

An Album To Blow Your Mind

Galen Ayers picks the debut album from Pink Floyd’s crazy diamond.

Syd Barrett

The Madcap Laughs, 1970

“You would assume that being a musician and the daughter of Kevin [Ayers, Soft Machine member, contemporary and friend of Barrett] that by now I would have explored this album in depth, but the truth is that it was only a few months ago that it blew my mind.

It was in the context of discussing different life experiences and songwriting roots with Paul that I started in earnest to rummage through the archives of my ‘prog’ heritage. The album has many producers: Harvest Records owner Malcom Jones, Peter Jenner, David Gilmour, Roger Waters, and of course Syd himself. You can tell at first listen that this is not a cohesive session.

I understand the recording process was polemic and saturated in anxiety to get the songs recorded before Syd’s mental health deteriorated even further. Nevertheless, for me, the songs evoke and create worlds and memories of their own. The reason this blew my mind is because it is a key for many musical doors that open onto my own musical map of the world. A part of why I love songwriting is that a good song changes meaning as time goes by. It travels, mirrors, reflects, tugs, and contextualises memories, time and time again. Of course, I knew that Soft Machine members played on this record, and that Syd was a mate of Kevin’s — so much so that Kevin wrote the ditty O Wot a Dream in honour of Syd.

Syd also joined Kevin on guitars on his debut solo album Joy of a Toy, released at roughly the same time as this.

For me, the album’s lyrical themes are interesting and deal with grappling with a sense of reality having been punctured… the floor and the ceiling seem subjective. In hindsight there has been some speculation on the effects acid had on Syd. This album sounds as if Syd is reaching out. The lyrical motif of hands can be found in many of the songs: No Man’s Land, She’s Long Gone, Terrapin, Dark Globe. To touch and be touched is the essence of his songs and that when you can’t, or you’re not allowed to, or shouldn’t, then making and listening to music is a way to connect to something larger than yourself. That is why this album is special to me.”