The New Cue #327 October 16: Pulp's Nick Banks; Bill Ryder-Jones in London

"We felt vindicated that people were finally getting into Pulp..."

Good morning everybody,

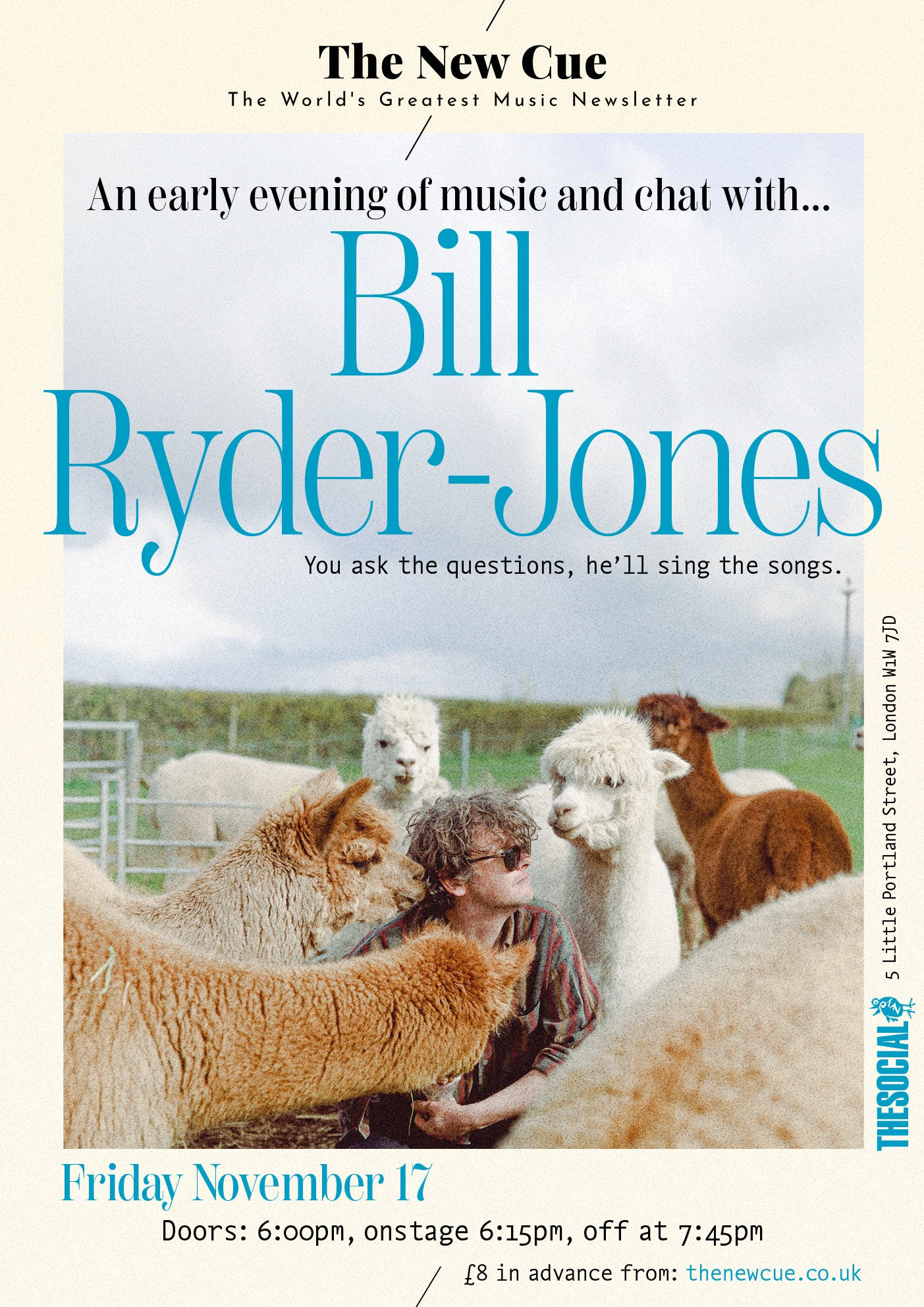

We open today’s edition with exciting breaking news: we will be hosting a very special early evening knees-up with the great Bill Ryder-Jones next month downstairs at the world famous Social in London’s swinging West End. It’s taking place on Friday November 17th. Doors open at 6:00 pm and the event starts at 6:15 pm on the dot. Tickets are £8:00. There’s will be just eighty places available from 11:00 am this morning, so if you want to join us click this link please.

Bill will indulge us in chat and acoustic song, drawing questions submitted by New Cue readers and the audience on the night from the same biscuit tin we used to use on the Q magazine podcast [nb: may not be exactly the same tin]. So if you want to ask Bill ANYTHING or request a particular song, drop us a line at thenewcue1@gmail.com, with Bill Requests in the subject line. Bill has made the first truly great album of 2024, Iechyd Da, which is out on January 12 via Domino, so we are extremely happy to have lured him into the basement of The Social. Here’s a taster of that masterpiece…

On with today’s edition now: Pulp drummer Nick Banks is here to give us the inside skinny on Jarvis Cocker’s 60th birthday party, the band’s early ‘90s transformation from art school outsiders to bona fide pop stars and whether we might be getting new Pulp music in the future. Why don’t you stick on a compilation of old Pulp hits while you read?

Enjoy the edition,

Ted, Niall and Chris

Start The Week With… Pulp’s Nick Banks

As a teenage punk growing up in Sheffield, Nick Banks played in various bands around the city before eventually joining Pulp in 1986. Pulp had been going for nearly ten years by that point, but it wouldn’t be until 1994’s His ‘n’ Hers that the group started to breakthrough, going on to become one of the biggest bands of the Britpop era. Having previously reformed in 2011, Pulp are currently on their second reunion tour, while Nick has just published his autobiography So It Started There: From Punk To Pulp, a dryly witty account of his life in Pulp and Sheffield childhood. Despite that busy schedule, Nick found the time a couple of weeks ago for a quick chat with Chris about Pulp’s past, present and possible future…

Hi Nick, how are you?

Fabulous! I’ve just been running around a bit, we just got back from London this afternoon and have been out for the dog walk. It was Jarvis’ 60th birthday party last night.

What did he do for it?

We went to this thing called Studio Dreamachine in Hackney and got some sensory overload with food and drinks, catching up with folk and big disco at the end. It was great.

Is there a gifting etiquette between the members of Pulp?

We don’t really do a lot. It was Candida [Doyle, keyboardist]’s birthday also recently. Everyone sort of says just come to the do rather than bother with a present, so we don’t bother unless you see something that’s screaming out at you that you think is completely on point for someone.

What’s the most unusual gift you’ve received from one of your bandmates?

Jarvis gave me a radio once, that was quite nice. An old radio that probably didn’t work, but that’s kind of par for the course.

When are you guys heading back out on tour?

In November. We’re going to Mexico, Argentina, Uruguay, which is a new country for us, which is always great fun. Chile, and then we’re gonna play in Hong Kong as well.

This has been your second reunion. How does the process start? Who blows the conch shell to get Pulp back together?

There’s only one person who can cry ‘Avengers Assemble!’, really. You don’t really want to be one of those bands who say we’re doing my version of Pulp and sod the rest of them. It would end up like the Bucks Fizz story. You’d end up playing at Butlins, Minehead or something. So Jarvis runs the flag up the flagpole and we see if we want to do it. We wouldn’t say no, because it’s great fun and we know how much it means to people who love Pulp, so we want to get out there and wow them with our wonky disco music and flared trousers.

Had you forgotten how much you enjoy it?

I don’t forget, no, because I do play in other bands, and we play gigs and I always enjoy that. The excitement of getting ready to go on stage and seeing people getting into it and having a great time. And that spurs you on to think, ‘This is why I’m doing it.’ I don’t want it ever to become a drudge. Because then, you might as well be working in a call centre. It’s what I’ve wanted to do since I was a teenager and it sounds cliché, but you’ve got to feel extremely honoured that you can get on stage and get paid for doing it. And do it for a considerable number of years. Why think it’s a bad thing, you know?

From writing the book you must have been sifting through your memory a lot. I wanted to ask you about Babies as that’s a song you co-wrote. Where were the band at in 1992 when you wrote it?

We signed our deal with Island in ‘92. We’d come through a really quite traumatic period of trying to extricate ourselves from a bad record deal. It was a very fraught time, you’ve kind of got this golden carrot over the horizon that you want to get to, but you’ve got these forests and swamps in front of you. So we had to tread very carefully to navigate through these choppy waters to get to where we needed to be. There were quite a few times when we thought Island Records were really interested in us but they could very easily get cold feet, and they very nearly did on a couple of occasions, and feel like: we can’t really touch this band because it’s just too messy. Thankfully, we were saved by Rough Trade, Jeanette [Lee, Pulp’s manager] and Geoff Travis who came along and helped us to untangle that and forge our way through the swamp to the golden carrot. ‘92 was a very, very pivotal year for us. It could have gone horribly wrong and I would have ended up a working in call center, but thankfully it came to pass that we got through the forest and grabbed our golden carrot.

When it came to the song itself, was it a bit of an accident?

Yeah, very much. I mean, a lot of songs are sort of accidental. You mess around and hopefully something good catches someone’s ear. It was one of those things where Jarvis and maybe Russell [Senior, guitarist] and Steve [Mackay, bass] had popped out into the yard for a smoke and as I’m very clean living and don’t smoke, I was just sat on an amp so picked up a guitar and started strumming. Just some of the few chords that I know. One of which was definitely a G, the other one, which it took me years to find out, was D Major seventh. Although I’m sure there might be a few guitarist out there who will tell me I’m wrong. So they came back from their smoking jaunt and Jarvis said, ‘What are those chords?’ Give us the guitar…’ He started strumming those two chords, just as I had been doing, so we all got back onto our respective instruments and literally within 20 minutes the song was done. It was one of those songs where we played it a couple of times and you kind of realise, ‘Oh, this is it’s fantastic!’ When we first played it, audiences got it straight away and it’s been in the set from that day on. That’s that sort of how I think songs should be done, rather than slaving away for weeks, months and years.

Did Jarvis talk about the lyrics to you, were they autobiographical?

Never. Mostly you don’t hear them until it’s actually down on tape. All you hear is what you’re playing in the rehearsal room and he’s just mumbling because he’s working them out in his mind, that sort of thing. Never ask, never tell. It’s kind of that blokey thing where you don’t sit down and say, ‘Tell us what that song is about? What are your darkest deepest innermost thoughts and emotions…’ It’s more like, ‘What trousers are you wearing tonight?’ That kind of thing.

Did you think you had something that you hadn’t quite managed to nail down before: an actual pop song?

You are always aiming for be able to do that. You notice that some songs are immediate, and some are less so. You just have to see what comes out of the ether in a way and go with it, but you certainly do get a feeling. Sometimes when you’ve done a new thing, you kind of go, ‘Oh that’s really interesting...’ But then sometimes something can be interesting for a bit and then die a death and not get anywhere, but that’s the vagaries of the whole thing, isn’t it?

Did it point towards a new direction for the future of Pulp?

Yeah, maybe. We always treated ourselves as playing pop music, rather than anything else like sludge core or rave. We wanted to have pop songs that were played on the radio and those two chords kind of did show a way forward that it was possible to do that. Some of our best poppy songs did come following along in that period. Razzmatazz, Do You Remember The First Time?, that kind of thing really did pull us into a different direction. Brighter, not darker.

When did you realise the Pulp were entering the sphere of being actual pop stars?

It was kind of in that period. We started putting out records that were getting into the lower reaches of the charts, but each one was getting a little bit higher than the one before and we were starting to play to fans who were actually getting into it. We weren’t playing to the semicircle of indifference anymore, where people were stood there with their arms folded like, ‘Entertain us, please…’ People were there, and they were into it and ready for the takeoff. Each one was getting a little bit better, but even so, in a way you don’t notice it so much. You see it as slow and incremental, you’re just plugging away thinking, ‘Oh yeah, that did alright. I think we’re getting there now...’

I’m assuming you didn’t immediately think you’d be playing these songs to several thousand people in 30 plus years-time, but was there an ambition for Pulp to be a big band?

If someone came into that room and said, ‘That’s a brilliant song, lads, you are going to be playing that to 1000s of people in 30 years-time in Uruguay, Hong Kong, Mexico and Argentina,’ we’d have been jumping around the room with joy. We probably wouldn’t have believed them, but it would have been great, because it would have been a pure example of this vindication of what we’d been doing for years. A lot of the time we’d just say, ‘Well, we think we think we’re good. We think we’ve got something valid to offer and if people get to hear it, then they can make up their minds, whether they like it or not and if they say: Not for me. Then at least we had a go. See you later…’ But thankfully, lots of people came to our gigs and all that kind of stuff. So it kind of went on. We were very happy to feel that vindication that people were finally into us and getting into Pulp’s music. The spotlight of interest is moving around all the time and it moved in our direction, and we kind of moved into the direction it was going. The spotlight came on us and the trick was to try and stay in that spotlight. But you never know which way it’s gonna go.

Playing with Pulp again, is there a desire to go back into the studio and make some more music together?

Well, doing that is very difficult. Because it would take probably three to five years to do and we’ve got other things we’d rather be doing at the moment, really. It’s gonna be difficult and I think you’ve just got to be realistic about where you are in your life. That’s one of the most horrible phrases in live music, isn’t it? ‘Here’s a couple from my new album...’ You do, ‘Right, piss, bar, and then by the time we get back, they’ll have finished.’ You might say that’s a cynical viewpoint but it’s probably true. So to be honest, no one is chomping at the bit to sit looking at each other in their rehearsal space, going, ‘Well, do you have any ideas?’ There’s little appetite for sitting and doing that for 18 months.

What if Jarvis called you up and said he had a bunch of songs and he wanted to make a Pulp record?

I’d probably say what I’ve just said, that maybe I wouldn’t really want to sit in a rehearsal room for 18 months trying to bang some tunes out. Because that’d be like almost like having a real job again. Maybe I’d give it a try for a week or two, but I wouldn’t be jumping on that train rapido because we very rarely did bring a bunch of songs into the recording studio or into the rehearsal room anyway. There might have been a couple of ideas, but like with Babies we’d often swap instruments to keep the technology or the technique level as low as possible. You’d jam stuff out and see what see what turned up. So if he called up and said he had half a dozen songs do you want to go through them now? I’d be like, Okay, let’s see... but I would be skeptical.

Thanks for talking to us Nick. I think you’ve got to shoot off now haven’t you?

Ooh yeah I have, I’ve just got a text. Thanks very much, take care!

CC