The New Cue #372 April 12: David Bowie, English Teacher, Automotion, Christian Music, Lemon Twigs, Hermanos Gutiérrez, Shabaka, Wunderhorse, Tertia, Oasis

"‘Man, it’s only rock’n’roll’.

Good morning,

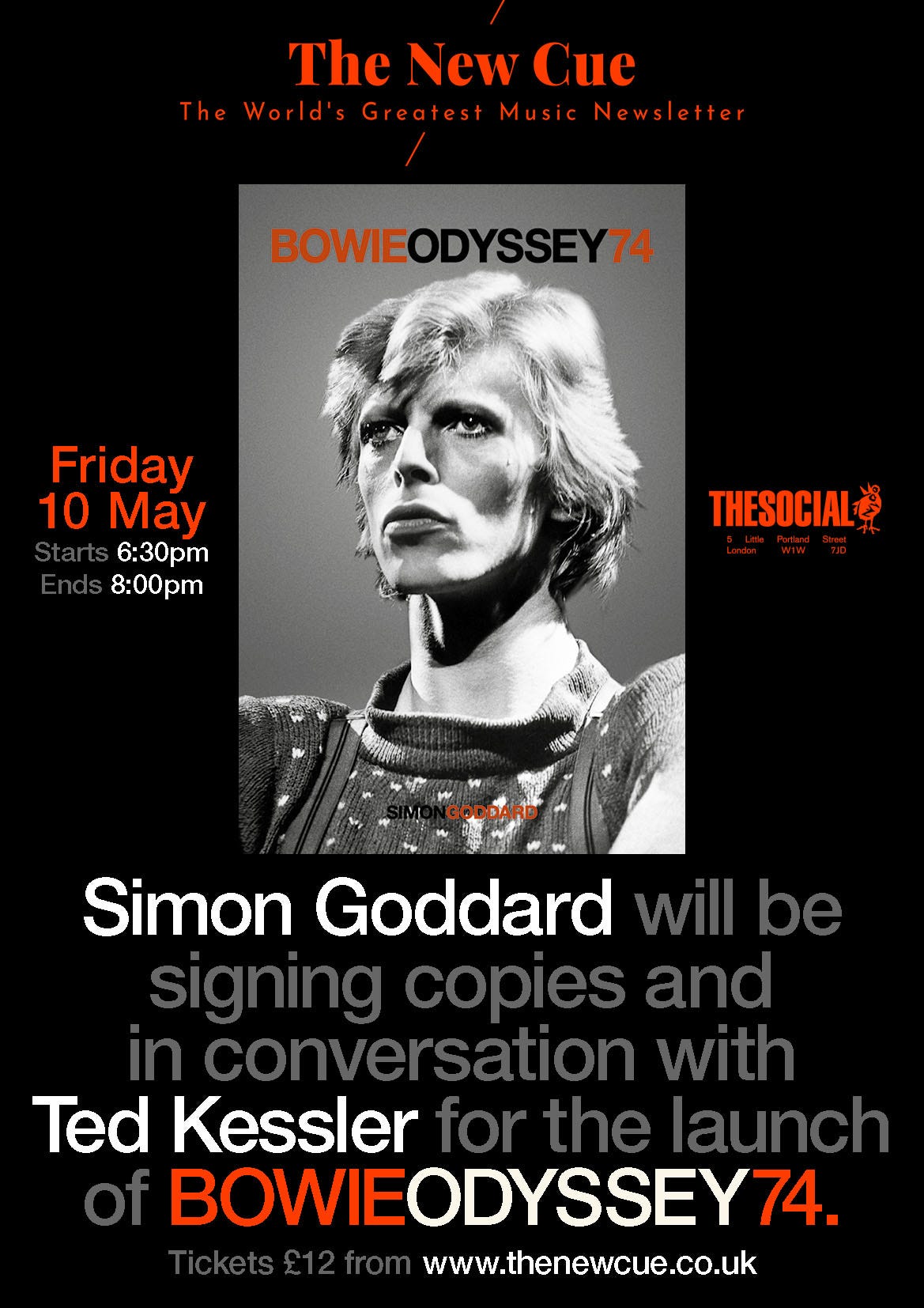

This is your weekly New Cue Friday Recommender edition and the very first thing we’re recommending is that you click on the link below and buy tickets to the launch of Simon Goddard’s BOWIE ODYSSEY 74 at the world famous Social, in London. Tickets are here

Looks good, doesn’t it? It’s a great book. We have an extract after the jump, for which we have very sexily lowered the paywall. Are you aroused? If that’s not titillating enough for you, then firstly: what’s wrong with you? Secondly, we’ll recommend some music too. There’s even a playlist to whet appetites:

Anyway, enjoy the edition and we’ll see you again on Monday for Niall’s chat with English Teacher.

Ted, Niall and Chris.

Bowie Odyssey 74: Extract

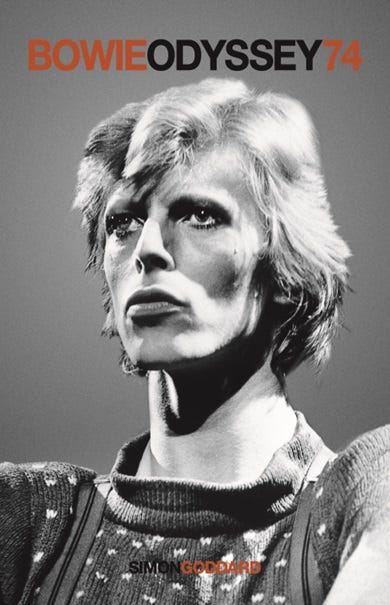

Next month The New Cue hosts the launch of Bowie Odyssey 74, the fifth volume in Simon Goddard’s epic 10-book series following the Starman through the 70s, published by Omnibus Press. They’ve been hailed as ‘immersive’, ‘novelistic’ and ‘a delicious romp’ in the words of Waterboy Mike Scott, while Marc Riley reckons this latest instalment ‘might be my favourite Bowie book ever’. Simon will be talking to Ted and signing copies at the Social on Friday May 10th between 6.30 and 8.00. As an appetiser, this extract finds Mick Jagger spying on Bowie at work in Barnes during the power-cut winter of early 1974 as Diamond Dogs slowly takes shape . . .

Olympic Studios. Where Mick recorded Sympathy For The Devil and the walls haven’t much changed in the five-and-a-half years since. The panels and screens are still mustard and orange, the square carpet tiles are still grey and the engineers still smell of extended lunch hours in the Red Lion. Only now there’s two studios. The one the Stones used and this newer one, Studio 2, where Mick perches on a plastic hourglass stool in the corner, lips puckering inquisitively as he watches David as a mother might her child playing in a sandpit: cross-legged on the ground surrounded by paper and pens among jack leads wriggling across the floor from one distant socket to another like tributaries of the Amazon basin; between his knees, the hardback 1974 desk diary he uses as a board to slice a handwritten sheet into strips, line by line, using a metal ruler and scalpel.

‘Cut-ups,’ he tells Mick. An old Dadaist trick he’s borrowed from his new pal ‘Bill’ Burroughs: you chop up existing phrases or sentences, then mix the different pieces at random to create abstract new meanings. Mick pouts a stifled laugh and shakes his head. Man! What the bloody hell does he think he’s doing?

He doesn’t know. That’s the beauty of cut-ups. You never do. You write, you chop, you scramble, you read, you decode. For David, it’s less about atom-smashing syntax than a form of psychic divination, a bit like tarot cards. Chance words come together and mysteries reveal themselves. Home truths. Past secrets. Future legends.

With every drag of the scalpel he severs himself from the dying fictions still bearing his name in this week’s papers. Yesterday’s doomed hopes, now today’s threadbare lies. His West End musical of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. His Broadway revue The Ziggy Stardust Show. His sequel covers album, the one he referred to as ‘Pin Ups 2’. All ancient histories discarded in the time it takes to shred one foolscap sheet into so much spaghetti. Cut up. Rearrange. Start again.

The songs that remain are now amputated body parts he must stitch together to make a brand-new monster. One no longer beholden to any fate once in store for Winston Smith or Ziggy Stardust, where the former’s We Are The Dead can conjoin with the latter’s Rock ’N’ Roll With Me leaving no visible scars. The failure to finish either musical all the way to a theatrical run becomes an unseen liberation. The only performance David now need worry about is the two-act play at 33⅓ rpm. The only leading role, himself. And while much of the scenery is still recognisably Suffragette City or Airstrip One, the libretto constantly changes according to whatever mental plagues possess him on any given day.

It could be Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, part of the Hampstead Everyman’s Classics of the German Cinema season which he’s taken to see the week after his 27th birthday, its Cubist sci-fi cityscapes etched so deep upon his eyeballs that every time he shuts their lids he can re-watch it like a flicker book. It could be Bill’s most recent novel The Wild Boys and its tribal gangs of ‘glider boys with bows and laser guns, roller-skate boys, blue jockstraps and steel helmets, 18-inch bowie knives’. It could be a late night visit from Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood, arms rattling with Liebfraumilch and an advance copy of the Faces’ live LP Coast To Coast: Overture And Beginners. It could be a sudden desire to change all the bulbs in the studio to red. It could be Mick laughing his usual ‘man, it’s only rock’n’roll’. It could be swastika nightmares of genocide.

David can do anything he wants because there’s no one to stop him. He employs a tiny handful of musicians who come in only when he needs them to play only what he tells them. Most of the instruments he plays himself – as he brags to Mick, ‘pretty well everything except piano and drums’ – and for the first time in eight albums he is his own producer, with no one to answer to other than his ego. And his ego, cornfed on sex and powdered plant toxins, is David Bowie’s biggest fan.

And why shouldn’t it be? Just listen to him sing.

There are people who cannot sing and when they try it’s as ugly as a rye-blind bum seeing how many parked cars they can bounce off till they crack their head on the kerb. There are those who think they can sing, deaf to their zombie-footed stiffness of patients dragging drips on castors. There are singers who plod, singers who stroll, singers who skip and singers who run. And there are those, not many, David being one of the chosen few, who dance. Not just any old ballroom foxtrotter or nightclub jiver, but a dancer. A Nijinsky, an Astaire. The sort of dancing that obeys its own gravity so they hang in the air longer than you think humanly possible, like there’s no crouching depths they can’t spring from and no cloudless heights they can’t spring to, their muscles moving as if in weightless slow motion, leaping strong as skyrockets, landing soft as feathers. This is how David sings. He has never not been able to sing, and he has never not sung well, but on these new songs he sings in arabesques and somersaults. Like a singer who wishes to be remembered and knows precisely when his voice is too beautiful to forget. Because if immortality was ever his goal, on these songs he signs his insurance policy.

As David’s Orwell album is rubbed out by his Ziggy album, is redrawn by his Wild Boys album, is crosshatched by his Metropolis album, he takes a last step back to try and make sense of what it all means. But there’s what he sings and what he says, and when the two join together they, too, might as well be random cut-ups.

He sings about a post-apocalyptic dystopia – then says it’s ‘a backward look at the Sixties and Seventies’. He sings about sex in doorways and taking drugs – then says it’s ‘a very political album’. He sings about deformity and Tod Browning’s Freaks – then says it’s ‘my protest’. He sings of feeling scared and lonely – then says ‘this album is more me than anything I’ve done previously’.

Unless it’s true? David, secretly a little scared and perhaps genuinely lonely, whether he’s here with Mick or Bill or the studio ghost of Jimi Hendrix. Where time is not made of minutes but ticking white lines: paper strips, powder sniffs, mini-Moog keys and the barrels of Gitanes. Living like a bat between dusk and dawn, never seeing sunlight but for the few footsteps between home and car then car and studio. Perfectly isolated from the blacked-out hungry city around him, barricaded in his fortress against the armies of diseased mutants crawling out there in the darkness.

Tickets for our event with the author of this extract, Simon Goddard, on May 10th are here.

Recommender

Niall Doherty

I have been offsetting the wholesome vibes of a family holiday this week with the grim rancour of the new single by Christian Music. The follow-up to the excellently-titled Marimba-Tragic Death Cult, Feed The Monkey sounds like a car crash Eighties Matchbox, a band who often sounded like a car crash anyway so this is a car crash inside another car crash, a Russian doll of car crashes. Five minutes of enjoyably demented hollering, psychobilly riffs and clattering drums.

If some fools hadn’t have shut down Q, then right now I would be lobbying to appraise all the groups featuring rock star offspring in a Battle Of The Bands-style feature. There could be a rating system about how much influence and sound they’ve inherited from their parent, the more original and rebellious their approach compared to mum or dad’s band, the better their score – Inhaler, featuring Bono’s son Eli Hewson, would score low here because they often sound a lot like U2. But Automotion, featuring Liam Gallagher’s son Lennon on co-vocals and guitar, would be getting top marks. Even down to the title of new single Lost In The Spinal Labyrinth, they take on a very un-Oasis-y stance and this is a moody art-rock number with slow builds and rhythmic twists and turns, like a petulant Black Country, New Road. Oasis would hate them! Good stuff, top marks.

This Could Be Texas, the excellent debut album by Leed four-piece English Teacher,

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The New Cue to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.